Photos: Koray Türkay

Click to read the article in Turkish (1) (2) (3)

The district governor of Pazarcık, Maraş, the epicenter of the first earthquake on February 6, seized aid materials intended for earthquake victims in the district.

The aid materials collected by several labor and professional groups and the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) had been stored in the office of the Hasankoca Neighborhood Assistance and Solidarity Association.

On Wednesday (February 15), the district governor, accompanied by the gendarmerie, visited the association's office. The authorities reportedly told those overseeing the association's activities that "you cannot distribute aid without our involvement."

The gendarmerie dispersed locals who lashed out at the intervention. Residents of Pazarcık have been complaining about the lack of aid distribution and search and rescue teams in the region.

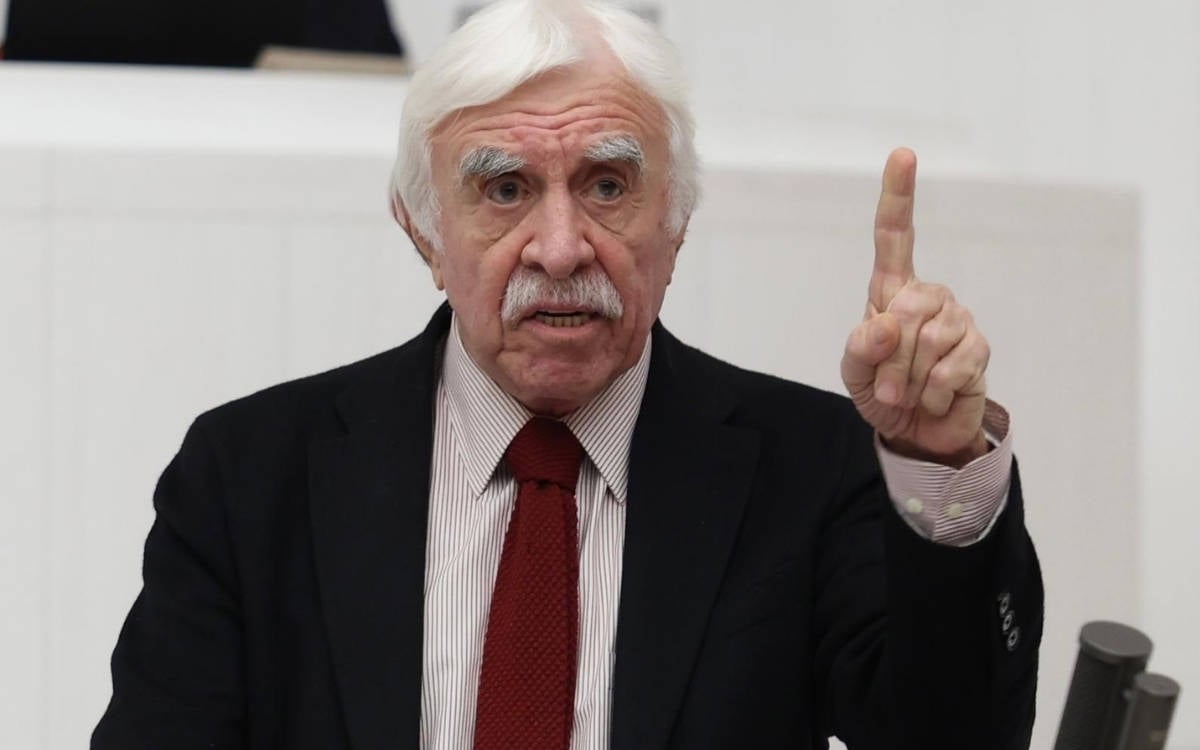

Koray Türkay, the co-chair of the HDP's Kadıköy district organization in İstanbul, who is also coordinating the Hasankoca Neighborhood Association's relief efforts, explained their work and the authorities' intervention to bianet.

"We went to the villages not yet reached"

"We set up this coordination center 10 days ago at the building of the Hasankoca Solidarity Association. We organized a strong solidarity network together with 150-160 volunteers. We especially went to the villages which were not yet reached. We went to 30 to 45 villages in a day. We detected if there were collapsed houses and who lived in the villages," Türkay said.

"We established a network of solidarity that is well-disciplined and well-organized. People who had also seen other coordination centers also told us that this place was different.

.jpg)

"We did not only take food but also heaters to the people, we set up tents. We distributed clothes, hygiene products, sleeping bags, blankets, and medicine. We set up a health team. We turned our caravan into a mobile health station and went to all the villages. The Health Directorate also asked us to support them and we did."

Why then has the district governorship taken this place over?

"The center in Pazarcık also drew the attention of the international press. Again representatives of the UN came there. They made a report stating that this place is a safe place for the aid to arrive. We believe that the reason for the intervention was this. They appropriated all aid materials.

"One trailer truck arrived just then. We had many important aid materials on this truck. Heaters, propane cylinders, vegetable oil, many other things.

"We would be carrying all of these carefully from one person to another. But they lifted the truck bed and dropped off all in front of our eyes! The propane cylinders were full, they may have exploded. This is a shame. This is more than disregarding our labor, our desire for solidarity, it is humiliation. They say I have the power, I can do anything, and armed ones accompany them," Türkay to bianet.

.jpg)

"We will rule"

He added, "This all happened when the chairperson of the Diyarbakır Chamber of Industry and a crowded delegation were all here. Pazarcık district governor and his armed men raided here. He told them that they will be the ruler here from now on. We told that this was a trustee appointment, and he told us "as you wish to understand it."

Seven Alevi organizations made a joint statement and denounced the appropriation of aid materials as "unacceptable."

The organizations underlined that Alevi organizations throughout Türkiye and also in Europe were collecting aid and sending aid materials and it was unacceptable that the governorships or officials appropriated them or prevented their distribution. (TY/EMK/AEK/VK/PE)

.jpg)

as.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)