Click to read the article in Turkish / Kurdish

The Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) has released a written statement on the occasion of May 15 Kurdish Language Day. The statement in Kurdish and Turkish briefly said the following:

"Hawar magazine, which started its publication life in Latin letters on 15 May 1932 in Damascus, the capital of Syria, and published 57 issues until 1943, is considered a milestone in terms of Kurdish cultural historiography.

"This initiative for a cultural revolution led by Alî Bedirxan and his comrades 88 years ago continues to inspire Kurdish language and culture studies today."

A clip made by Zarok TV and Yerevan Radio for the Kurdish language day: |

"Published under the leadership of Celadet Alî Bedirxan, the Hawar Magazine's Latinizing Kurdish letters has a revolutionary historical significance. Because of its contributions to Kurdish, May 15, the day the magazine's publishing life started, has been acknowledged and celebrated as Kurdish Language Day since 2006.

"Oppression on the Kurdish language and culture continues on the Kurdish Language Day as well. Kurdish and multilingual studies within the municipalities are prevented, TV channels, newspapers, magazines, agencies in Kurdish, daycare centers, institutes and associations providing education in Kurdish are shut down.

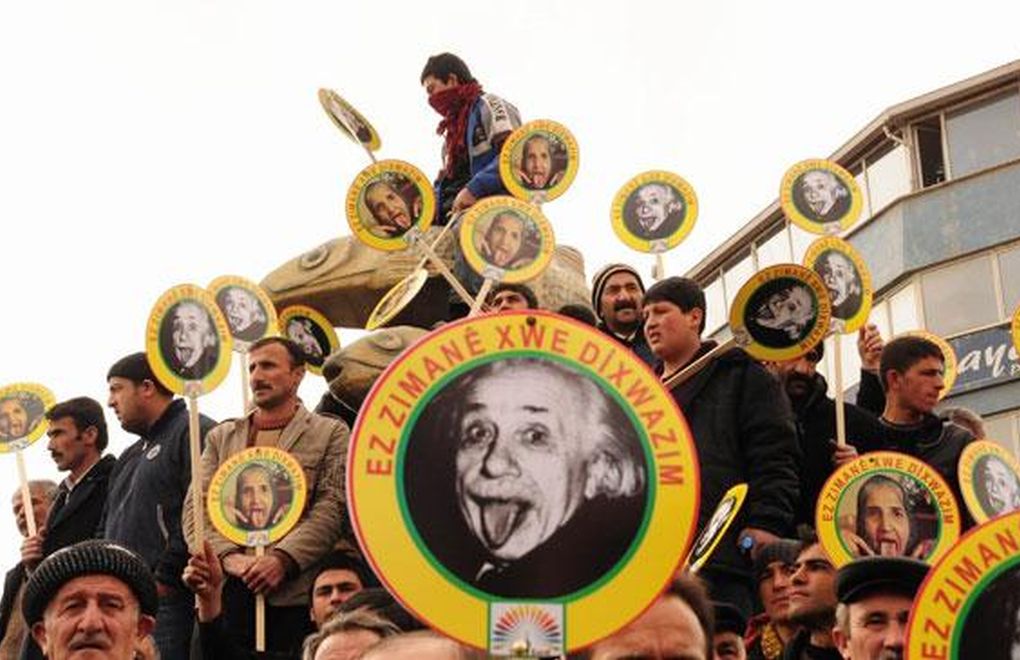

"On the Kurdish Language Day, reiterate our call for the removal of oppression on the Kurdish language, especially the demand of education in the mother tongue, we emphasize our demand of an amendment regarding Article 42 of the Constitution.

"We reiterate our call to the authorities to comply with the international agreements that pave the way for education in the mother tongue, which is the most fundamental human right.

"On the 88th anniversary of the Hawar Magazine, we greet those who made the Kurdish language live and develop in the person of Celadet Alî Bedirxan and celebrate the Kurdish Language Day." (RT/VK)