Click to read the article in Turkish

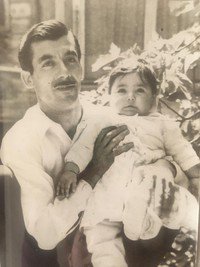

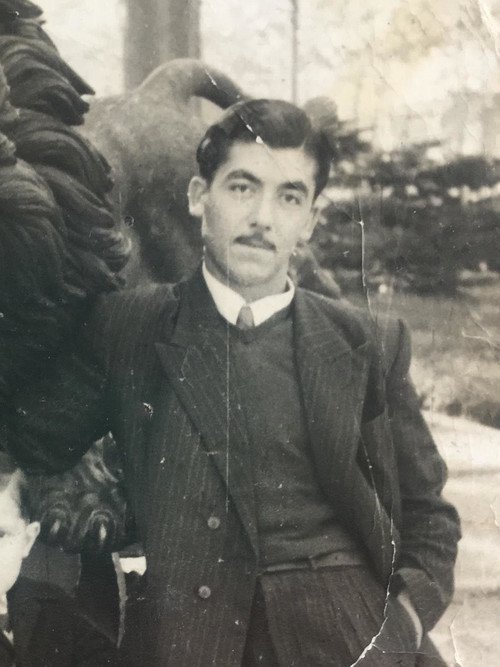

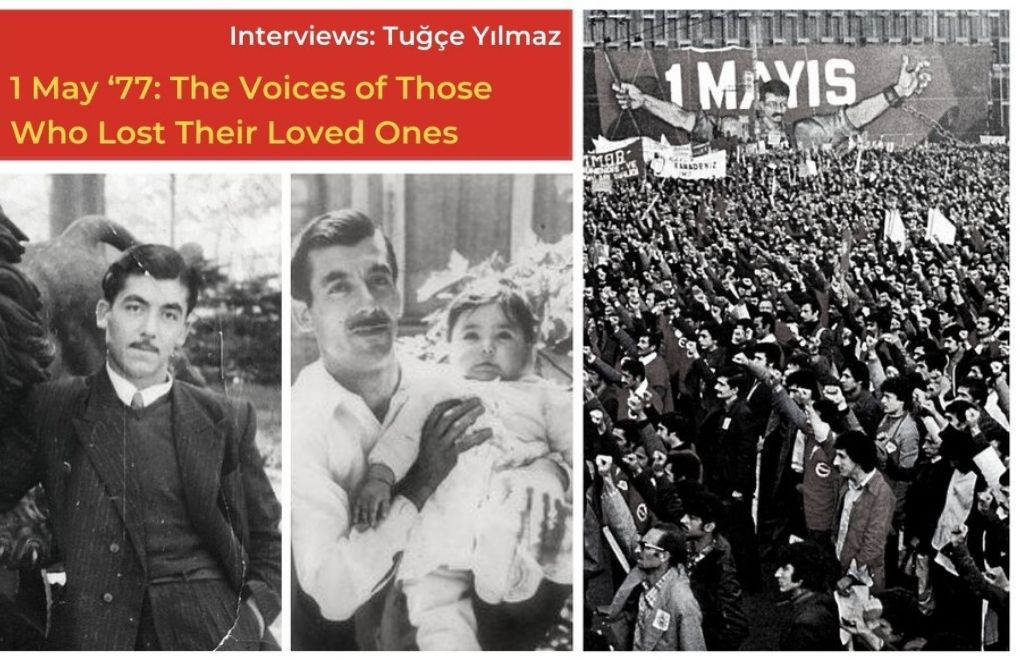

Rasim Elmas, film industry worker.

One of those whose lives was taken on Kazancı Slope on the 1st of May 1977, a date that has gone down in modern history of Turkey as "Bloody First of May."

Rasim Elmas was 41 years old when he lost his life. Known for his generosity and for always helping those in need, he was often called by the nickname "Dayı" [meaning "Uncle"].

According to the autopsy report, the cause of death was mechanical asphyxia as a result of rib fractures and compression of the chest, along with cerebral oedema.

Birsen Kement was only 17 years old when she lost her father, Rasim Elmas. When she was told at Police Headquarters, "You'll find your father in the morgue," she didn't even hear the word "morgue." She was excited that she would be able to find her father. But, she says, when she opened her eyes on Monday, on 2 May, she had "doubled in age overnight."

Birsen Kement talks about the 1st of May 1977, which she recalls moment for moment, telling us about her father, Rasim Elmas, and how her life changed after his death:

My dad worked in  cinema. He was a film industry worker.

cinema. He was a film industry worker.

He went to check in on the film company that day, to see if there were any problems with the machines. Before that, he'd warned me, with a kind of parental instinct, not to go to the First of May rally that weekend. That Sunday, both of us were at home and it was almost like we kept checking each other, watching to see who would leave first to go to the square.

Around 3-3.30pm my mum and I left, to go visit my uncle's family; but of course, that was just part of my plan. I wanted to be able to leave the house so I could then go to the square. My dad left home after we did.

That Sunday, I left without giving him a kiss goodbye. Because I was thinking, better not be too affectionate and give him the chance to hold me back. That has always weighed on me.

My dad's friends saw him after he left around 3-3.30pm. In fact, he ran into a director friend of his who said to him, "Why are you going there, it's so crowded." My dad never liked crowds. Even when he walked along the street, he always walked in the middle of the road, saying, "You never know, a couple could get in a fight and break the windows and something could fall on my head." He was that careful.

But he still went. Both of us were at the square that day; but I ended up arriving later than my dad did. By the time I got there, all hell had already broken loose, I was only able to get as far as this spot where everyone was making their way to Harbiye. I couldn't get to the actual square. But then I guess all this happened around 7.30pm. My dad was there and in fact, he'd spent about two hours at a clubhouse run by a relative of ours before he even went to the square. It was while he was on Kazancı Slope making his way home that it happened.

I know what happened from the people who were there, from our friends who survived. It's said that shots were fired from the Water Administration Building and also from the Intercontinental Hotel that were both located there on the First of May Square. That led to chaos and pandemonium. And it was around 7.30-8pm, during the speech by Kemal Türkler, president of the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey [DİSK], that the real explosion happened.

We finally made it home but my dad didn't show up of course. My brother and I had a journal and we were writing some stuff in it. I was so sad and upset about what had happened that day, and as I kept wondering what all had happened, who all had died, I wrote down these lines by Nâzım Hikmet in the daybook: "If you don't burn, and I don't burn, how ever shall the darkness emerge into light." Of course, at the time I didn't yet know that our own family was amongst those who were burned.

My dad didn't come home that night, or the next morning either.

Sometimes he didn't come home because of work, because the film company would call him in or he'd have to go somewhere, for example. But when it got late and he still hadn't showed up, we all began to sense something was wrong.

My brother and I made a decision; he himself was still just 16 years old, he hadn't yet done his military service. We decided to split up—I said that my mum and I would go check at the police headquarters, and he should go to the hospitals. So that's how we did it.

First we went to Gayrettepe, Mecidiyeköy. That's where the Second [Police] Precinct was. It was absolute chaos there. Then they told me, "You might find your father in the morgue, or try the First Precinct."

So the words "First Precinct" and "morgue" kept going round and round in my head, but really, at that moment, I was just excited at the prospect of finding my dad. I mean, I was happy we were going to find him.

What my mum and I saw when we reached Taksim Square though was just horrifying. The pavement was wet, it was slick with blood and water. There were socks and undershirts strewn on the ground, and clubs of various lengths with nails sticking out of them... It was as if war had broken out and this was one of the battlegrounds.

Then we went to the First Precinct. We passed through these round, wooden places. I gave my statement to the police of course, and they asked me questions... There was this fair-haired officer, I'll never forget him. "You'll find him at the morgue," he said, and I was elated. Of course I thought I'd find my father alive. The friend who had taken me [to the precinct] brought me back home, where I found my brother. It was like he'd gone mad. "I found dad. Dad's dead," he said. I don't remember what state I was in after I heard the words "found" and "dead."

My brother had found our father at the morgue, they'd put him in one of the drawers at the morgue.

They made us pay some six lira for his body. We had to pay to get his body out of the morgue. We took him to the Ortaköy Mosque and from there to the Aşiyan Cemetery where our family burial ground is.

At my age now, the things I experienced back then no longer seem that horrible to me—because we experienced such dreadful things after the 1st of May 1977 as well. Torture, suspicious deaths that were never investigated, murders; explosions, all of the things that the youth and their families went through back then... When I compare my father dying at the age of 41 to all of that, what I went through then no longer seems so horrible to me.

There are people who've been tortured, who've been in prison for 20 years or more. What I suffered is next to nothing really, compared to what so many of our friends and comrades have been through. But for years I felt this pain in my back—because that's how they killed my father, by trampling on him and crushing his back.

Though I don't know the exact circumstances under which he fell, I could never shake the image of that crowd, the smoke, and my father's back being crushed.

On the other hand, we were also told that there was a knife wound on his arm. We weren't allowed to see the autopsy report at the time. I don't know if it's still possible to obtain it now or not, I'd like to see it.

Back then there was an organisation for film industry workers called Film-San. And I think, though I'm not certain, that they were prejudiced about my dad being at the First of May demonstration, because back then, Film-San leaned more to the right. After my dad died, they didn't offer us support of any kind; in fact, they didn't even come to pay their condolences.

After my dad died, I doubled in age overnight. In a manner of speaking, I was the one who became my mum's husband, so to speak. I had to look after everything.

'He even ironed his money'

My dad was a modern, enlightened man. No one talked much about politics at home, but when we reached 12 or 13 years old, my brother and I began to understand and discuss the world, and, for example, to read the classics. My dad left us to our own devices for the most part. But when he died, I had a kind of epiphany. I asked myself all kinds of questions: Why did your dad die? Who killed him? What is celebrated on this holiday anyway? Why did it turn so bloody?

My dad was a humanist.

The two of us had a very different kind of relationship. I still live in the house my dad left us, I've been here some 50 years.

As a little girl, I was in love with my father. We'd write poetry together. We'd take trips on the weekends, we'd even go out for a beer together now and then.

He loved to travel, he was always going somewhere. He was a very stylish man. He even ironed his money. And his circle of friends was a rather colourful bunch too. Sometimes I think to myself, he lived life so fully while he was alive, because his life was bound to be cut short.

He was always helping those who'd suffered some misfortune. His nickname was "Dayı" [Uncle]. Not because he was the tough, masculine uncle type, but because he was so generous, always helping those in need. I'm not saying this just because he's my dad, everybody knew my dad to be like that. I can't say he was like this or like that politically, that he was "this kind of right-winger" or "that kind of leftist". Because he wasn't.

He was a slim man, and a very elegant man, delicate and graceful.

He grew up without a mother, so maybe that's why he was so emotional. He always told me, "You're my mother too, you're everything to me." I remember during the Cyprus Conflict of 1974, he cried so much. He'd cry so much for the orphaned children. My mum and dad weren't really alike at all. For both of them it was their second marriage. I mean, as I understand it, neither of them was able to find what they were looking for.

My dad was doing contract work at the time. And he had about 900 days' worth of insurance. We didn't get anything from any kind of insurance though, like a survivor's pension, life insurance, worker's compensation insurance, none of it. My mum was an illiterate woman from Anatolia. The only thing we had was this home we're sitting in right now. We had no income. And since my dad was the only one in the family who worked, we didn't have any kind of security. So of course it was a very difficult time for us. There were days our mother made us soup from flour. So, I mean, it's true what they say: "The ember burns wherever it falls"—that's what happened to us.

So even though my dad wanted nothing more than for me to get a good education, after his death, I had to quit school and start working. Think about what life was like 40 years ago. Think about the state of consciousness back then, what it meant to survive. First I got a job at a laboratory, then at a publishing house, at Gelişim Publications. Since I started working at 18, I retired at 38. I worked during all that time and after too.

1 May 1977 filled me with such anxiety about the future, that I always lived with this feeling that something bad could happen to us at any moment, and that we mustn't depend on others.

Although physically my life may not have changed that much, intellectually and psychologically, it changed a lot. Besides dealing with the emotions of a girl who's lost her father, I had to bear the weight of knowing what it means to be a labourer on Labour Day. And after that day, I too became a true labourer.

For me, it wasn't so much Sunday but Monday that was important. Tuesday was very important. Every day after that was so important. After my dad died, the windows through which I viewed life became much more meaningful. I tried to look with a more precise eye, with a better outlook. Sometimes I wonder if I'd still be the kind of person I am, if my dad hadn't died the way he did. That has something to do with the stuff a person is made of too, of course, but for me the connection with my father is so precious. I thank him for raising me the way he did.

My dad didn't deserve to die that way. Nobody deserves to die that way. Only people who've lost their fathers at a young age, who have endured poverty, and survived such a blow, can understand me. They'll understand what remains unspoken.

'They thought even a memorial was too much'

On 1 May 1977, 34 people died, 8 of them women. As far as I know, most of those families have left Turkey. There are just a few of us families left, that you can meet with, that you can see in person. I'm also on the executive committee of the 78'ers Foundation. We did our best to see that the judicial system address all these crimes. It's clear of course who the perpetrators are. This massacre was organised by powers that include counterinsurgency forces. Turkey has a very powerful intelligence organisation. Do they really not know who did this? How can they not? For us, it doesn't matter if they reveal the perpetrators to be Ahmet so-and-so or Mehmet such-and-such. We know who did this. But we don't know in whose name they did it, the source of this brutality. We don't understand.

One dimension of the reason my dad was there that day is fate, but then there are also the dimensions of mind and logic, of consciousness, of course. But no matter how we look at it, it was inevitable that we experience something like this. 1 May 1977 contributed so much to the lives of me and my family, but it caused us tremendous loss as well.

What happened on 1 May 1977, was a harbinger of what would happen later in Turkey, sociologically and psychologically. That's how I see it. Later, it would be compounded by the massacres in Sivas, Maraş, Ankara, and everything that happened in the South East. In this respect, 1 May 1977 was a turning point.

And I don't think they misunderstood us, because they didn't misunderstand my dad, they understood him perfectly well. They didn't want us, they didn't like us, precisely because they understood us. They did away with the fruit of a tree by tearing off its branches one by one. Unfortunately, we are facing mighty imperialist forces, but we are here, and we continue to exist. So long as the world turns, this conflict will continue, but our struggle will continue too.

Everyone was there to laugh that day. They were on the First of May Square to celebrate the holiday. That day was a holiday. There was a huge crowd. Whoever pushed the button, it resulted in that holiday turning to bloodshed.

We consider the First of May a day of commemoration. If it were a holiday, then all people, regardless of religion, language, or race, would have been compensated for the sweat of their brows. We just wanted it to be a holiday. We just wanted peace.

We've asked many times for something to be done. We asked that we be able to commemorate our dead on Kazancı Slope. At the very least we wanted a memorial to be erected there, with the names of our dead. Many of our friends appealed to the European Court of Human Rights, I myself didn't; but I don't think there is a statute of limitations for crimes against humanity. I'm a person who loves her country, I would take no pleasure in taking my country to the Court of Human Rights. But sadly, no one did anything for us, they did nothing to take care of us. The state should have looked after us. Instead, we looked after ourselves.

We just wanted for Taksim Square to be renamed the First of May Square, and for there to be a memorial erected there with the names of our dead on it. But they thought even that was too much to ask.

Up to now we've been told not to go there, and now we're dealing with the pandemic. We've always been told to go to Bakırköy, or to Kadıköy. But a commemoration doesn't really mean much to me if it's not held in Taksim. Have I gone to the marches? Of course I have. But if you ask me, the call to come to the other squares is for the workers, while Taksim is for a "commemoration."

I'm going to go to Taksim this year too. The various organisations are going beforehand for the commemoration. I am someone whose father was killed, was murdered there. I'm going there not to celebrate but to commemorate my father, and I do not think I will be stopped. (TY/DB/SD)

About Tuğçe YılmazJournalist, editor, researcher. "1 May 1977 The Voices of Those Who Lost Their Loved Ones / 1 May 1977 and Impunity" she was engaged in this dossier as a researcher, reporter, editor and writer. Her articles, interviews and reports are published in outlets such as bianet, BirGün Book, K24, 5Harfliler, Gazete Karınca and 1+1 Forum. She graduated from Ege University, Faculty of Literature Department of Philosophy. She was born in Ankara in 1991. |

|

| This text was created and maintained with the financial support of the European Union provided under Etkiniz EU Programme. Its contents are the sole responsibility of "IPS Communication Foundation" and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. |

CLICK - 1 May 1977 e-book is online

The ones who lost their lives on 1 May '77The ones whose loved ones we could talk to: Ahmet Gözükara (34, teacher), Ali Sidal (18, worker), Bayram Çıtak (37, teacher), Bayram Eyi (50, construction worker), Diran Nigiz (34, worker), Ercüment Gürkut (27, university student), Hacer İpek Saman (24, university student), Hamdi Toka (35, Seyyar Satıcı), Hasan Yıldırım (31, Uzel worker), Hikmet Özkürkçü (39, teacher), Hüseyin Kırkın (26, worker), Jale Yeşilnil (17, high school student), Kadir Balcı (35, salesperson), Kıymet Kocamış (Kadriye Duman, 25, hemşire), Kahraman Alsancak (29, Uzel worker), Kenan Çatak (30, teacher), Mahmut Atilla Özbelen (26, worker-university student), Mustafa Elmas (33, teacher), Mehmet Ali Genç (60, guard), Mürtezim Oltulu (42, worker), Nazan Ünaldı (19, university student), Nazmi Arı (26, police officer), Niyazi Darı (24, worker-university student), Ömer Narman (31, teacher), Rasim Elmas (41, cinema laborer), Sibel Açıkalın (18, university student), Ziya Baki (29, Uzel worker), The ones whose loved ones we did/could not talk to: Aleksandros Konteas (57, worker), Bayram Sürücü (worker), Garabet Akyan (54, worker), Hatice Altun (21), Leyla Altıparmak (19, hemşire), Meral Cebren Özkol (43, nurse), Mustafa Ertan (student), Ramazan Sarı (11, primary school student) The ones only the names of whom are known: Ali Yeşilgül, Mehmet Ali Kol, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı The one whose name is unknown: A 35-year-old man |

The voices of those who lost their loved ones: 1 May '77 and impunity

Political panorama of Turkey-1977

Film industry worker Rasim Elmas, 41, died in Taksim

Construction Worker Bayram Eyi, 50, died in Taksim

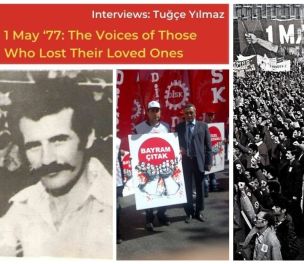

Teacher Bayram Çıtak, 37, died in Taksim

High School Student Jale Yeşilnil, 17, died in Taksim

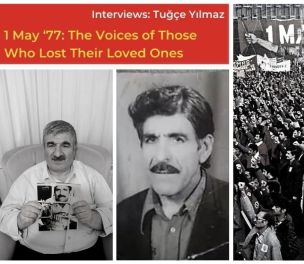

Teacher Kenan Çatak, 31, died in Taksim

Teacher Ahmet Gözükara, 33, died in Taksim

Teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü, 39, died in Taksim

Student-laborer Niyazi Darı, 24, died in Taksim

University student Nazan Ünaldı, 19, died in Taksim

Teacher Ömer Narman, 31, died in Taksim

Laborer Ali Sidal, 18, died in Taksim

Counterperson Kadir Balcı, 35, died in Taksim

Student Hacer İpek Saman, 24, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Kahraman Alsancak, 29, died in Taksim

Laborer Hüseyin Kırkın, 23, died in Taksim

Student Ercüment Gürkut, 26, died in Taksim

Public order police officer Nazmi Arı, 26, died in Taksim

Laborer Mahmut Atilla Özbelen, 26, died in Taksim

Factory worker Hasan Yıldırım, 31, died in Taksim

Itinerant salesperson Hamdi Toka, 35, died in Taksim

Security Guard Mehmet Ali Genç, 60, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Ziya Baki, 30, Died in Taksim

Laborer Mürtezim Oltulu, 42, Died in Taksim

Teacher Mustafa Elmas, 33, Died in Taksim

Student Sibel Açıkalın, 18, died in Taksim

Laborer Diran Nigiz, 34, died in Taksim

1 May 1977 & Impunity

'The state is implicated in this crime, perpetrators must be put on trial'

'If you can't find the killers, you can't remove the stain'

'The perpetrators of the 1 May 1977 massacre got away with it'

Remembrance as a matter of dignity and the fight against impunity

Who is hiding the truth and why?

-132.jpg)