Click to read the article in Turkish

"Until now, my uncle's story has never been published anywhere. Nobody has heard his life story; this is very saddening for us. I'm not sure about my other relatives, but the feeling of having no voice always deeply upset me."

"He was an honourable, dignified man. He earned his money through hard work; in his short life he never gained anything in a way that wasn't honourable. There was once a man named Ahmet, his surname Gözükara [meaning 'fearless'], he was from Elbistan, he died on the First of May."

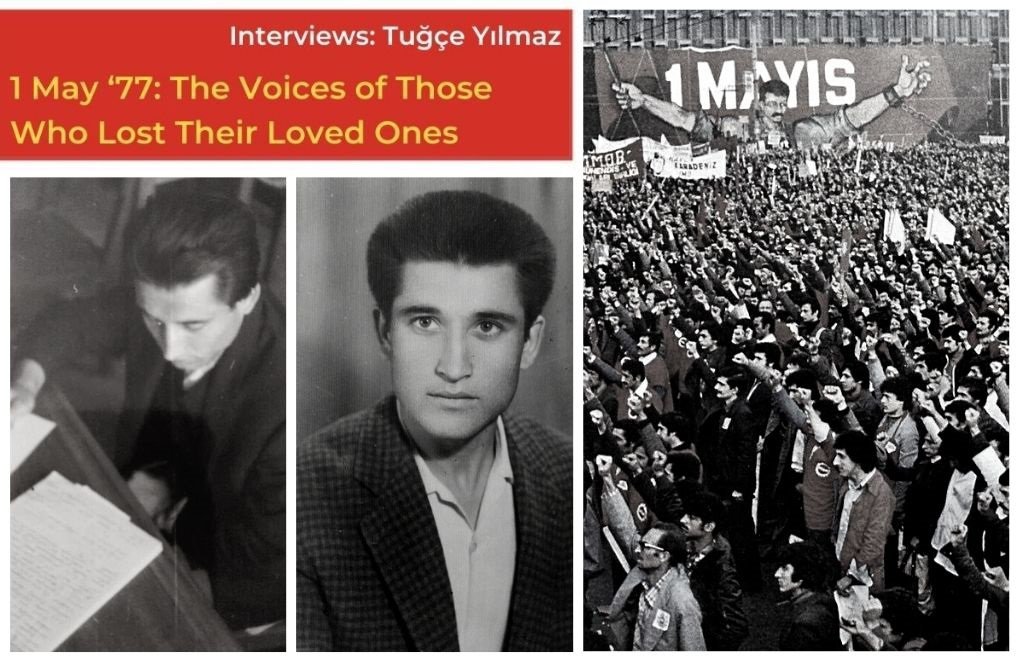

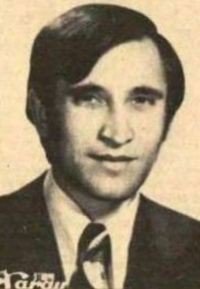

Ahmet Gözükara is one of those who died on 1 May 1977 whose story had never before been published. Like the other teachers who lost their lives in Taksim that day, he was a member of the Alliance and Solidarity Association of All Teachers [TÖB-DER].

Ahmet Gözükara moved from Maraş to Istanbul in 1972, when he was appointed to a position at the Sultanahmet School of Commerce. He was only 33 years old when he lost his life in Taksim.

He was the first person his family lost at such a young age.

Previously, all that was known about Ahmet Gözükara was that he was a teacher at the Sultanahmet School of Commerce and a member of TÖB-DER.

According to the autopsy report, the cause of his death was mechanical asphyxia due to compression of the chest and abdomen, along with cerebral oedema.

Until today, no relatives had spoken about him, neither had any of his friends.

It was very difficult for me to reach his niece, Sema Gözükara, but once I found her, she accepted my invitation to talk about her uncle.

Before I contacted Sema Gözükara, I found that every year she commemorated her uncle in different ways.

This was one of my motivations for reaching out to her.

Sema has never forgotten her uncle and proudly honours his memory every year.

She told me that she would do as much as she could for the story of her uncle, who she loved deeply and remembers fondly to this day, to be heard.

Sema Gözükara and I spoke about Ahmet Gözükara, and she told me how her life and the lives of her large family changed after his death. She also spoke about how his eldest brother, Ali Kemal Gözükara, who was extremely fond of Ahmet, was affected by his death and about his lament to his brother in a book named, "The Ballad of the First of May", and about much more.

Sema Gözükara, niece:

So far, my uncle's story has never been published anywhere. Nobody has heard his life story; this is very saddening for us. I'm not sure about my other relatives, but the feeling of having no voice always deeply upset me.

I visited the "Museum of Torture" when it was first opened in Ankara, and my conscience was wounded when I saw that my uncle did not appear among those killed on 1 May 1977, not even as a photograph. This was an unsettling feeling.

I came home and found a photo with my uncle in it. Using the possibilities of technology, I had his image enlarged; I then had his photo framed and gave it to the museum. The people at the museum hadn't been able to find any information about Ahmet Gözükara and were very happy to have found a trace of him.

My uncle was a person to be proud of, to boast about even. I would really like everyone to know about his story, his life, about who he was as a person.

We're from Elbistan. It's not quite in the east, but Elbistan is close to the border of Eastern Anatolia. Families there are large and very close knit.

A model relationship

Everyone in Elbistan knows the Gözükara family. Because of this family structure, our uncles were always part of our lives. This close relationship with our relatives lasted until we had to move away from Elbistan when I was nine years old.

My uncle was a teacher at the Elbistan Middle School. He had also been my father's pupil. Of all his siblings, my father was particularly fond of Ahmet, and Ahmet of him.

They were eight siblings, but Ahmet was really special to my father.

They had a model relationship based on love and respect. Sometimes in the summer months, when they would come to see us in Ankara, I would listen to their conversations.

My uncle had a great amount of respect for my father. You know the way you love the people your mum and dad love; well, we really loved my uncle because my father was so fond of him and because he was so affectionate and protective towards us.

I remember that they talked in quiet but worried voices about the frightening course of events in the country, the brutality of capitalism, and oppression. The 1970s were years when despotism rose rapidly.

Because my father was a teacher from the Village Institute tradition, they called our family "faithless communists" too. But like my father, Ali Kemal Gözükara, his family also practiced their beliefs in private.

My uncle has always held a positive place in my memories. First of all, he was a very affectionate man—principled, fair and interested in others. He was a good person and a very good teacher. He was 33 when we lost him. He was very young.

Mahzuni Şerif

One day, I think it was 1967, there was a Mahzuni Şerif concert in Elbistan. As you know, Mahzuni was an Alevi singer-poet.

Reactionaries from the Elbistan region came and raided the concert. Mahzuni Şerif's friends managed to get him out of there somehow.

At that time we lived in Bahçelievler, a neighbourhood outside the city. They'd gone to a couple of houses but no one had opened the door to them; I'm not sure if it's because they weren't in or because they were scared. Then they came to our house; my mum was at home.

My mum is a very brave woman. She opened the door and hid them in the guest room. Then my mum sent my big sister to the city centre to tell my dad and uncle what had happened.

I remember my dad and uncle arriving in a jeep, putting Mahzuni Şerif in a car and sending him to his village, and I remember my uncle in his white trenchcoat. They didn't seem at all scared.

However, even if we weren't Alevi, that rabble could have killed us because they saw us as "communists". I clearly remember the brave stance my mum and my uncle took.

My uncle was someone who had no primitive emotions like greed; he saw money not as an end but as a means. He was an honourable, dignified man. He earned his money through hard work; in his short life he never gained anything in a way that wasn't honourable. And so, this honourable name is the biggest legacy handed down from a father to his children.

A reader of Cumhuriyet

He was an avid reader of the Cumhuriyet newspaper. I remember that very well because he would analyse everything, even down to the adverts, and comment on them for all of us to hear.

My uncle was an idealist; just like the other members of our large family, he always tried to do things for the good of the nation. He also helped to bring the first cooperative to Elbistan. Like I said before, my father, Ali Kemal Gözükara, was a teacher from the Village Institute tradition.

One day, the reactionaries from the city attacked the teacher's canteen and put my father in a coma. I was only small, but this incident burned itself into my memory.

I remember my uncle squeezing my father's hand, and saying angrily, "You sacrificed yourself for these people and look what they've done to you." But this anger never turned to malice. He tried to approach events in a rational way, always tried to offer flowers even to his enemies.

Moved from place to place

Even though the Gözükara family weren't Alevi, they supported the Alevi struggle for their rights. And on top of that, the label of us being communists meant that the many teachers in our family were constantly being appointed to teaching positions in different areas of the country. Even after my father was put in a coma, it wasn't the perpetrators who were punished, but my father, who was sent to Maraş.

My uncle had also been transferred to a post in Maraş before we were sent there. They stayed there for two years. My uncle's first child was born there. Two years after his daughter was born, he was transferred to Istanbul, to the Sultanahmet School of Commerce. They went there in 1972, but unfortunately he was only able to live there for five short years.

My father had retired, but my uncle wanted us to come to Istanbul too. My father even sent him his retirement bonus. My uncle was organising everything.

All our belongings were ready, and in 1977 we too were going to move to Istanbul. Of course, after my uncle's death, this never happened. Our lives went in a completely different direction.

His second daughter and his son were born in Istanbul. He had three children. His son was just nine months old, I think. After my uncle died, we completely lost touch with his children.

"Large numbers dead"

On 1 May 1977, my older brother and my cousins all went from Ankara to Istanbul for the First of May celebrations. My uncle also went to Taksim, both to check on them and look after them—because he'd caught wind of the bad atmosphere—and also, naturally, as a worker.

They went there that day in high spirits.

On the evening of 1 May 1977, we were watching the evening news. I'll never forget it—we were eating dinner, even that stays in my memory. There was a news announcement saying, "Large numbers dead at the First of May demonstration." In those days the music for the TV news began with the disquieting sound of a bell.

There were lots of political incidents, people were dying every day and that music had become a traumatic sound for us. But still, when they said, "Large numbers dead," it never crossed our minds that my uncle was one of them.

"No! My brother's gone..."

When the names of the dead were being read out, they said my uncle's name too; because of the driving licence in his pocket, they said he was a driver. My uncle's driving licence was the first thing they found.

We thought it wasn't my uncle, but someone with the same name; or maybe that's what we wanted to believe. You know what they say, "The ember burns wherever it falls," so at that moment you want it to be someone else with the same name. "He can look after himself," we said. We turned our attention to my older brother and my cousins who'd gone there with him that day.

In the morning my brother found a telephone and called my aunt's house. "I'm okay," he said. But when he got home he told us, "On the bus they were saying my uncle died." Later we learned that, unfortunately, my uncle really had died.

My dad banged his fists on his knees and said, "No! My brother's gone; his children are fatherless." I remember how much my dad suffered back in those days, it was like he would never again want anything to do with life. But time is merciless. There's no pain that time can't make you forget.

"My son stepped here"

After hearing the news, my relatives went to Istanbul to collect his body. Such a painful moment. My grandfather; a veteran of the War of Independence. He went up to the door of the morgue and begged, "I have a veteran's medal, show me my son's body."

They buried him in Istanbul, in the Zincirlikuyu Cemetery. After the funeral, my grandma and grandpa lived with us for a short time. I remember my grandma kissing the stairs in the house, saying, "My son stepped here."

In the words of his student

A former student of his who lived in Ankara told this anecdote. One day my uncle was solving a problem in class. His student said, "Sir, I think your answer is wrong." My uncle called him up to the board and said, "Okay, come and show us the right answer."

His student thought that my uncle would be angry, that he would reprimand him, but my uncle said, "Come see me at breaktime." The student went.

My uncle said, "If you study, you could achieve great things. You really should go to university." The student's eyes filled with tears. He was such a democratic and fair person who valued other people, that's who he was.

Never forgotten

Of course, I would have liked to know my Uncle Ahmet better. I had four uncles on my father's side, but he was different. He was very special. Just imagine, from the moment you open your eyes you are faced with an uncle who your father never stops talking about, who everyone says is very kind, and who is extremely caring towards you.

When my uncle died, I was a mess for days. I was 17 at the time. Those who loved him shed the most tears for his children who had lost their father.

As far as I've heard, his children never faced any financial difficulties thanks to my youngest uncle; after their father died, they studied at the best schools.

Time has passed since the tragic event; wounds have healed but nothing has been forgotten. We always wore my uncle on our breasts like a mark of pride.

I always remember him with love, for the kindness he showed us. For exactly 43 years I have commemorated him every night in a spiritual way. I still have this desire to be close to him.

I hope that in this way his story will, at least to a certain extent, be known.

There was once a man named Ahmet, his surname Gözükara [meaning "fearless"], he was from Elbistan, he died on the First of May. (TY/APA/YK)

About Tuğçe YılmazJournalist, editor, researcher. "1 May 1977 The Voices of Those Who Lost Their Loved Ones / 1 May 1977 and Impunity" she was engaged in this dossier as a researcher, reporter, editor and writer. Her articles, interviews and reports are published in outlets such as bianet, BirGün Book, K24, 5Harfliler, Gazete Karınca and 1+1 Forum. She graduated from Ege University, Faculty of Literature Department of Philosophy. She was born in Ankara in 1991. |

|

| This text was created and maintained with the financial support of the European Union provided under Etkiniz EU Programme. Its contents are the sole responsibility of "IPS Communication Foundation" and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. |

CLICK - 1 May 1977 e-book is online

The ones who lost their lives on 1 May '77The ones whose loved ones we could talk to: Ahmet Gözükara (34, teacher), Ali Sidal (18, worker), Bayram Çıtak (37, teacher), Bayram Eyi (50, construction worker), Diran Nigiz (34, worker), Ercüment Gürkut (27, university student), Hacer İpek Saman (24, university student), Hamdi Toka (35, Seyyar Satıcı), Hasan Yıldırım (31, Uzel worker), Hikmet Özkürkçü (39, teacher), Hüseyin Kırkın (26, worker), Jale Yeşilnil (17, high school student), Kadir Balcı (35, salesperson), Kıymet Kocamış (Kadriye Duman, 25, hemşire), Kahraman Alsancak (29, Uzel worker), Kenan Çatak (30, teacher), Mahmut Atilla Özbelen (26, worker-university student), Mustafa Elmas (33, teacher), Mehmet Ali Genç (60, guard), Mürtezim Oltulu (42, worker), Nazan Ünaldı (19, university student), Nazmi Arı (26, police officer), Niyazi Darı (24, worker-university student), Ömer Narman (31, teacher), Rasim Elmas (41, cinema laborer), Sibel Açıkalın (18, university student), Ziya Baki (29, Uzel worker), The ones whose loved ones we did/could not talk to: Aleksandros Konteas (57, worker), Bayram Sürücü (worker), Garabet Akyan (54, worker), Hatice Altun (21), Leyla Altıparmak (19, hemşire), Meral Cebren Özkol (43, nurse), Mustafa Ertan (student), Ramazan Sarı (11, primary school student) The ones only the names of whom are known: Ali Yeşilgül, Mehmet Ali Kol, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı The one whose name is unknown: A 35-year-old man |

The voices of those who lost their loved ones: 1 May '77 and impunity

Political panorama of Turkey-1977

Film industry worker Rasim Elmas, 41, died in Taksim

Construction Worker Bayram Eyi, 50, died in Taksim

Teacher Bayram Çıtak, 37, died in Taksim

High School Student Jale Yeşilnil, 17, died in Taksim

Teacher Kenan Çatak, 31, died in Taksim

Teacher Ahmet Gözükara, 33, died in Taksim

Teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü, 39, died in Taksim

Student-laborer Niyazi Darı, 24, died in Taksim

University student Nazan Ünaldı, 19, died in Taksim

Teacher Ömer Narman, 31, died in Taksim

Laborer Ali Sidal, 18, died in Taksim

Counterperson Kadir Balcı, 35, died in Taksim

Student Hacer İpek Saman, 24, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Kahraman Alsancak, 29, died in Taksim

Laborer Hüseyin Kırkın, 23, died in Taksim

Student Ercüment Gürkut, 26, died in Taksim

Public order police officer Nazmi Arı, 26, died in Taksim

Laborer Mahmut Atilla Özbelen, 26, died in Taksim

Factory worker Hasan Yıldırım, 31, died in Taksim

Itinerant salesperson Hamdi Toka, 35, died in Taksim

Security Guard Mehmet Ali Genç, 60, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Ziya Baki, 30, Died in Taksim

Laborer Mürtezim Oltulu, 42, Died in Taksim

Teacher Mustafa Elmas, 33, Died in Taksim

Student Sibel Açıkalın, 18, died in Taksim

Laborer Diran Nigiz, 34, died in Taksim

1 May 1977 & Impunity

'The state is implicated in this crime, perpetrators must be put on trial'

'If you can't find the killers, you can't remove the stain'

'The perpetrators of the 1 May 1977 massacre got away with it'

Remembrance as a matter of dignity and the fight against impunity

Who is hiding the truth and why?