Click to read the article in Turkish

"They really persecuted us. I cut out all the articles and stories about my dad from the papers and put them in a folder. In the 1980 military coup I gave it to my mum to hide, she told me she had hidden it in the coal cellar. But I think she had to burn everything, because afterwards I couldn't find any of the documents. I only have a few left. We lost my father but he was the criminal. We were [the criminals]. Not only did we lose a family member, our darling father, but we were also persecuted for it as though we were the guilty ones."

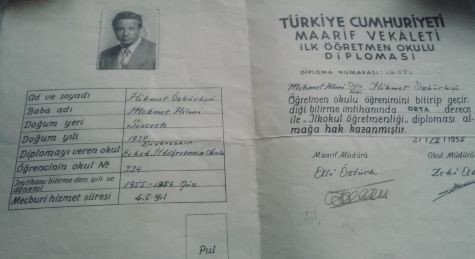

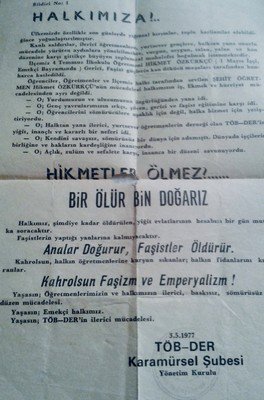

Hikmet Özkürkçü was a teacher and member of the Alliance and Solidarity Association of All Teachers (TÖB-DER). He was also the head of the Karamürsel branch of TÖB-DER. He taught at the 4 Temmuz Primary School in Karamürsel. He was just 39 years old when he lost his life in Taksim.

According to the autopsy report, the cause of his death was internal bleeding caused by penetrating injury to the chest and abdomen from a bullet wound.

He had four children: Behiye, Bülent, Hilmi and Devrim.

So far, most of the information known about him came from the memorial announcements in the local newspapers of Kocaeli. Although some family members had spoken about him, no detailed information was known about Hikmet Özkürkçü.

I tried to reach out to Hikmet Özkürkçü's family based on information found in articles from the local newspapers. A relative helped me to connect with Hikmet Özkürkçü's daughter, Behiye Özkürkçü.

Behiye was also with her father in Taksim on 1 May 1977.

Behiye Özkürkçü spoke about what kind of father and teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü was, how her life changed after her father's death, what she learned from him, and the events of 1 May 1977, which she remembers as though it were yesterday.

Behiye Özkürkçü tells

I was born in 1961. I'm retired now but I too am a member of the teachers' union, Eğitim-Sen. My father was born in 1938 in the city of Siverek in Urfa. He graduated from teaching college and studied in Sivas and Diyarbakır. He married young, at the age of 23.

He stayed in Siverek  for a while, and then was exiled to Viranşehir for political reasons. From Viranşehir he was moved to Gebze. His transfer to Karamürsel was his own choice. After living in Gebze for two or three years, we moved to Karamürsel, where we lived for a long time.

for a while, and then was exiled to Viranşehir for political reasons. From Viranşehir he was moved to Gebze. His transfer to Karamürsel was his own choice. After living in Gebze for two or three years, we moved to Karamürsel, where we lived for a long time.

Throughout his teaching career, my father was very involved with TÖB-DER. He was the president of the Karamürsel branch of TÖB-DER. He was a great support to the young revolutionaries there. In particular, he really looked out for those who'd been in prison.

He was a very kind and friendly teacher. He saw his students as his children. I'd like to tell you a story about this, that could almost be a joke. My father taught the morning section classes. Me and two of my siblings were in the afternoon section. When he came home, we would be heading to school. Occasionally we'd play truant, of course, one of us in particular skipped school a lot and my dad would get really mad.

One day my dad comes home and my mum opens the door. He sees my mum hasn't sent us to school. My mum says, "But Hikmet, the kids really were sick. They're all coughing, they're tired, that's why I didn't send them to school." My dad says, "You know, Zekiye, you're right. My kids were like that too, they were all sick, so I sent them home."

He was very devoted to us. He loved children in general.

I have three other siblings, I'm the oldest. And then the last one, Devrim, has a mental disability. He was born in 1970. Devrim really affected our lives, and mine in particular as the oldest child and as his sister.

My dad was always like a bridge between me and my mum. He always told me that I had to support my mum. And he said to her that she had to support us, that living with a brother like that was difficult for us too, that we couldn't lead our lives in a normal way. He was a calm man who always found the middle ground.

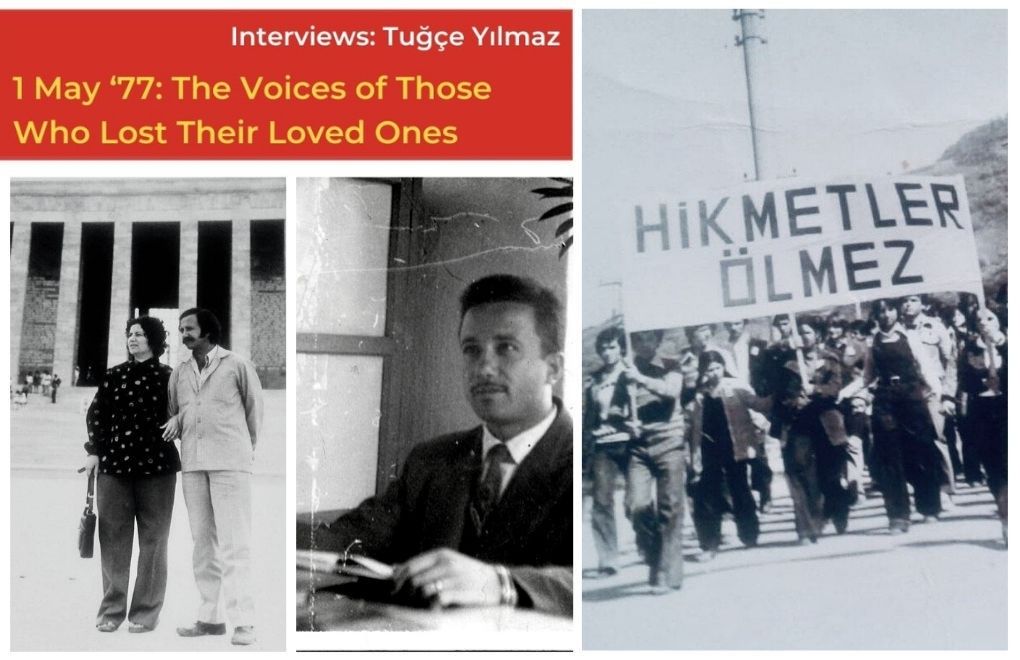

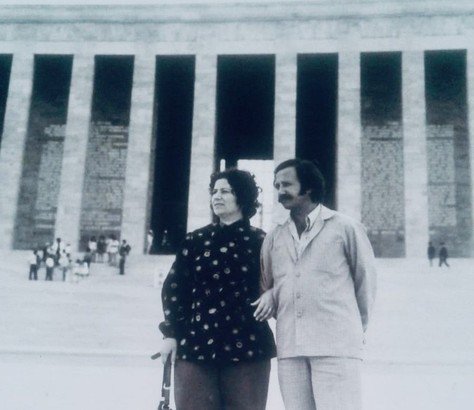

My mum and dad

He liked to have a drink with his friends, I remember that very clearly. In Viranşehir he'd get together with the important figures of the community, and in Karamürsel with the members of TÖB-DER. But he never got drunk. He would always keep his wits about him and drop everyone around the table off at their homes.

My mum never went to school. She got married off at a very young age, at 14. She was still 14 when I was born, and she had four children one after the other.

My mum was very clever, a very intelligent woman. She passed away too. She taught herself to read and write and also started learning English; she read the novels of Maxim Gorki.

She had to bring up four children, one with a mental disability, on her own, but she still joined the Progressive Women's Association. She opened up her house to the association for meetings and was actively involved in their activities.

She got involved in the association after my dad died, but like I said, before that she had read such books and broadened her horizons.

Preparations for the First of May

As the president of TÖB-DER, it was of course my dad who carried out the organisation in Karamürsel for the First of May rally. He had a difficult time, nobody wanted to take us; he found a young driver and managed to convince him.

Before 1 May, my father had made us a promise: "From now on, I'm going to take one of you to each demonstration, starting with Behiye."

And the first demonstration after that was the First of May.

Under normal circumstances, he had to take me. He'd made a promise and I was expecting it. But, as you know, there were rumours about 1 May, rumours that there might be some provocation. My school was on the edge of the city. One day I went out at breaktime and I saw my dad in the schoolyard.

"I want to talk to you," he said. "I made you a promise, Behiye. I also want to take you to Taksim, but there are some complications," he said, and told me about the turmoil of the time and his concerns.

Then he said, "Look, you could be injured, you could be arrested, you might get hurt or be scared. To be honest, I don't want you to come. But if you insist on coming, we'll go. Think about it until the evening and then tell me your decision."

In Taksim

Of course I wanted to go. The next morning we got up early and got ready. If my disabled brother woke up early he'd get very agitated and wouldn't stop crying. As we were quietly leaving, trying not to wake him, Hilmi woke up. To make sure Devrim didn't wake up and start crying and wake the others, my dad said, "Get your brother ready, let's take him too."

I was 16 years old, Hilmi was seven or eight.

It was a fun journey. After getting off the minibus we walked for quite a while then took our place in the square. We were just below the hotel. Then everyone found their own group, the youngsters were on one side, the TÖB-DER teachers on the other.

Because I'd stayed with the group of youngsters, my dad would occasionally come over and say, "Are you hungry, I'll buy you a sesame ring if you're hungry, shall I get some water?" On the fifth floor of the hotel I saw men using a tripod and a long telescope.

I asked my dad about them. He said, "Sweetheart, these are the government's men, here to keep an eye on us," and then went back to the TÖB-DER group.

He was shot

Then it all kicked off. We heard the first gunshots and people yelling, "Down! On the ground." I lay down, my father was also on the ground and we looked at each other. We stood up and took a few steps. My father fell. He called over to his friends for help, "Guys, I've been shot in the leg." But no one was in a position to help anyone else.

I only managed to get to within about a metre of my dad. He stood up again, but fell after taking two or three steps. This time he fell on his back. There were no bloodstains or signs of a bullet wound.

But the bullet had gone through his sweater and shattered his internal organs.

The hole made by the  bullet wasn't visible without pulling off his sweater. We lost the death certificate, but I remember it saying, "Police bullet".

bullet wasn't visible without pulling off his sweater. We lost the death certificate, but I remember it saying, "Police bullet".

I later looked for the certificate everywhere but couldn't find it.

After that, a young guy came and took me, I was in shock. I remember I was in shock because I kept jumping up and down. The young guy convinced me to leave the square. He took me to a part of Istanbul where there were small cafes one next to the other.

Of course he asked me where I'd come from, how I got there. Then he found the group from Karamürsel, handed me over to them and left. My friend Yahya and my brother weren't there either. I was so busy thinking about my father that they hadn't crossed my mind, but I later heard from Yahya, he'd been taken into custody.

Seeing him for the last time

After some time passed, another young guy like the one who'd brought me to the Karamürsel group brought my brother this time, then left. We waited until 3am. I'm not sure if they'd received news about my father or not, but they decided there was nothing else for us to do, so we got on the minibus and went back to Karamürsel. We arrived in Karamürsel around 3.30am.

We received the news.

The funeral was held after my dad's body arrived. I really wanted to see my dad; I begged them to let me see him one last time. But no one let me.

Except for one person. One of the union leaders said, "Let her see him, let her rage grow."

He showed me my father's body. I wish I hadn't seen it. I broke down. I wish I'd never seen my father like that.

I'm not sure if I was scared at that moment, or sad. But his mouth was open, you could see his teeth.

You know what, after that day, every time I saw a chimney vent, that image would come to my mind. It was like I saw that image of my dad's face in those chimney vents. And I also saw it in the waves of the sea, for some reason...

The first moment that I realised I had completely lost my father was about a month after his death. Twenty days after my dad died, my uncle passed away. He couldn't cope with the pain of losing his brother, we thought; we lost him too, to a brain haemorrhage. We buried my uncle.

Solidarity

Afterwards, a table was set for dinner, and I put down a plate for my father too. I noticed straight away of course and took it away, but I went into the bathroom and wept. In our family, everyone would hide their sadness. My mum would hide her sadness too, so as not to upset us.

After my dad died, my mum couldn't work. She had no school certificate, but mainly my disabled brother made it impossible for her to work. Devrim needed constant care.

TÖB-DER, the teachers in Karamürsel, our neighbours, and the unions within the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey [DİSK] looked after us really well. Until we started receiving my dad's pension payouts, they did our shopping, paid our rent and bought our coal.

TÖB-DER in particular looked after us really well. But some awful things happened too. Money was collected for my dad in some factories, and those kind people generously gave as much as they could to help us. But that money never reached TÖB-DER or us. The only money that reached us was the money collected by the union.

Anyway, they handled the money and met our every need. Everything from our school expenses to our winter firewood...

His friends fought to get my dad's pension paid. As far as I remember, my dad's retirement bonus was a good one. His friends added money from their own pockets to that money and bought us a house. For a long time it was them who looked after us. I'll never forget their kindness.

I didn't receive a teaching appointment

After my dad's death, our lives changed a lot. Hilmi became a teacher, like my dad. He's at a school in Izmir now.

My other brother, Bülent, didn't have the chance to study, for reasons out of his control. Bülent lived in Karamürsel, but his school was in İzmit. The school was full of leftists and democrats, but on his journey to school there were nothing but right-wingers.

Bülent was beaten up a few times on that journey. Both by the right-wingers and by the police. That's why he had to drop out of school. Thanks to one of our relatives, he got a job in a shop. That man was really good to him, he later left the shop to Bülent.

As for me, after graduating from the Gazi Faculty of Education, I was faced with a financial investigation that I didn't pass.

And everything was written in that report: "From Siverek, Kurdish, her father was a member of TÖB-DER, he died in Taksim."

For three years I didn't receive a teaching appointment. I suffered a lot. All my dreams and ideals were destroyed. I even worked as a cleaner in a shop because of that investigation. I just wanted to work but I couldn't get a job anywhere.

In the third year I somehow received an appointment. In 1979, I was in Mamak [Prison] because of my political activities; that also had an impact, but I think the main reason was that my father was Hikmet Özkürkçü.

The union was like our second home after my father died. This one memory comes to mind about this. Going from İzmit to Karamürsel by road was expensive, crossing by ferry was cheap. So of course Bülent had to travel by ferry.

Because it was winter, after leaving school he'd go to the union to kill time while waiting for the ferry. One day, the police raided the union. They slapped him and said, "What are you doing here?" And Bülent said, "I'm waiting for the ferry."

This made the police mad and they beat him even more. But he really was waiting for the ferry. This was the kind of thing that meant Bülent had to drop out of school.

'Life is hard'

I have lots of memories of my dad, but one bad memory in particular stands out. I was really struggling with having to look after my disabled brother.

One day, I had an exam for an important class, I was studying but my brother wouldn't keep still. Whatever I did, he just couldn't stay still. My friends were also calling on me to come out and play.

I kept checking my brother's nappy, he'd get really agitated if he'd done something, so I thought I'd change his nappy, and if something was irritating him, I'd clean him up. But nothing.

One time when I was checking his nappy, I slapped him on the bottom to make him be quiet. He was a pale-skinned boy and his bottom immediately turned red. When I saw the red mark, I cried uncontrollably for hours. I cried and cried, but it didn't make me feel any better.

Eventually I went to the medicine cabinet and swallowed a load of pills. Nothing happened to me because I kept throwing up. Even though we were in the same house, my mum didn't notice anything for a long time; finally, on the second day, my dad said, "Sweetheart, you seem a little sluggish, are you ill?"

He kept on at me, saying, "There's something wrong with you." I burst into tears and told him, "You didn't even notice," I said.

He took me and we walked to the hospital. I'll never forget that journey. He spoke to me so nicely. "Life is hard," he said. "It's hard for you, for me, for your mother. It's even harder for you, I know, you can't enjoy your childhood. But be a little patient, so many good things will happen to you. Life won't always be like this. What would I have done if you had died, how could you do this to me?"

We went to the doctor, who said it was too late to do anything, that the pills had already entered the bloodstream, and gave me other pills to treat it. He said, "You have to take these pills once every ten minutes." And my dad stayed with me until the morning, giving me those pills every ten minutes, without missing a single one.

Fighting to end inequality

One day, my dad and I were walking along the shore in Karamürsel. My dad's teacher friends were with us too. As we passed through an area where the rich people lived, one of his friends said, "Hey, times are going to change; one day all this will be ours.

My dad got really mad at this. "This is exactly what we're fighting against, and you want to be in their place?" he said. And he really was fighting to bring an end to those luxury buildings, to inequality.

One day, while walking in İzmit, a man with a religious beard and robes came towards us. After he'd passed, my dad let out a curse. I took him to task about this, saying, "You tell us to do one thing, you do something different. Why?" He said to me, "Behiye, these are the only people I'm scared of. They won't miss any opportunity given to them. I only do this to them. They don't accept or understand anyone. When they come to power, they won't even grant you the D in democracy." Thinking about it now, in those days there wasn't even an organised religious movement, my father told me all this 50 years before.

He never finished The Grapes of Wrath

My father really liked Yılmaz Güney, because he came from the same town as us and was a leftist, and also because he liked him as an actor.

He took me to see all his films. But I couldn't really watch the film, because afterwards he would ask questions like, "What was it about, what did the main character do, what do you think they should have done?" And I could never answer.

He would get together to read books with his friends, I remember that. He never finished The Grapes of Wrath.

My dad's grave is in  Karamürsel. TÖB-DER had a gravestone made for him. And they had a beautiful grave made too. The gravestone read, "Revolutionary Teacher and Martyr, Died in Taksim Square in 1977."

Karamürsel. TÖB-DER had a gravestone made for him. And they had a beautiful grave made too. The gravestone read, "Revolutionary Teacher and Martyr, Died in Taksim Square in 1977."

Gravestone

On the first holiday after my dad's death, my mum went to visit his grave. She saw the grave surrounded by gendarmes who were pulling down the gravestone. They said they had to take the gravestone to the courthouse. I mean, couldn't they just take a photo? Did they really need to tear it down?

And did they have to do it on the first day of the holiday. This was just the first time; it happened a few times.

The soldiers were doing this with the excuse of taking the gravestone to the courthouse under court order.

The person who wrote the text on the gravestone was my literature teacher. You wouldn't believe the things that happened to him. My teacher was a migrant from Bulgaria, he shouldn't have got involved in these things. Because of the persecution he had to pack up all his things and move somewhere where he couldn't be found.

My father was still the criminal

They really persecuted us. I cut out all the articles and stories about my dad from the papers and put them in a folder. In the 1980 military coup I gave it to my mum to hide, she told me she had hidden it in the coal cellar. But I think she had to burn everything, because afterwards I couldn't find any of the documents. I only have a few left.

We lost my father, but he was still the criminal. We were [the criminals].

Unfortunately, we not only lost a family member, our darling father, but we were also persecuted for it as though we were the guilty ones...

(TY/APA/SD)

About Tuğçe YılmazJournalist, editor, researcher. "1 May 1977 The Voices of Those Who Lost Their Loved Ones / 1 May 1977 and Impunity" she was engaged in this dossier as a researcher, reporter, editor and writer. Her articles, interviews and reports are published in outlets such as bianet, BirGün Book, K24, 5Harfliler, Gazete Karınca and 1+1 Forum. She graduated from Ege University, Faculty of Literature Department of Philosophy. She was born in Ankara in 1991. |

|

| This text was created and maintained with the financial support of the European Union provided under Etkiniz EU Programme. Its contents are the sole responsibility of "IPS Communication Foundation" and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. |

CLICK - 1 May 1977 e-book is online

The ones who lost their lives on 1 May '77The ones whose loved ones we could talk to: Ahmet Gözükara (34, teacher), Ali Sidal (18, worker), Bayram Çıtak (37, teacher), Bayram Eyi (50, construction worker), Diran Nigiz (34, worker), Ercüment Gürkut (27, university student), Hacer İpek Saman (24, university student), Hamdi Toka (35, Seyyar Satıcı), Hasan Yıldırım (31, Uzel worker), Hikmet Özkürkçü (39, teacher), Hüseyin Kırkın (26, worker), Jale Yeşilnil (17, high school student), Kadir Balcı (35, salesperson), Kıymet Kocamış (Kadriye Duman, 25, hemşire), Kahraman Alsancak (29, Uzel worker), Kenan Çatak (30, teacher), Mahmut Atilla Özbelen (26, worker-university student), Mustafa Elmas (33, teacher), Mehmet Ali Genç (60, guard), Mürtezim Oltulu (42, worker), Nazan Ünaldı (19, university student), Nazmi Arı (26, police officer), Niyazi Darı (24, worker-university student), Ömer Narman (31, teacher), Rasim Elmas (41, cinema laborer), Sibel Açıkalın (18, university student), Ziya Baki (29, Uzel worker), The ones whose loved ones we did/could not talk to: Aleksandros Konteas (57, worker), Bayram Sürücü (worker), Garabet Akyan (54, worker), Hatice Altun (21), Leyla Altıparmak (19, hemşire), Meral Cebren Özkol (43, nurse), Mustafa Ertan (student), Ramazan Sarı (11, primary school student) The ones only the names of whom are known: Ali Yeşilgül, Mehmet Ali Kol, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı The one whose name is unknown: A 35-year-old man |

The voices of those who lost their loved ones: 1 May '77 and impunity

Political panorama of Turkey-1977

Film industry worker Rasim Elmas, 41, died in Taksim

Construction Worker Bayram Eyi, 50, died in Taksim

Teacher Bayram Çıtak, 37, died in Taksim

High School Student Jale Yeşilnil, 17, died in Taksim

Teacher Kenan Çatak, 31, died in Taksim

Teacher Ahmet Gözükara, 33, died in Taksim

Teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü, 39, died in Taksim

Student-laborer Niyazi Darı, 24, died in Taksim

University student Nazan Ünaldı, 19, died in Taksim

Teacher Ömer Narman, 31, died in Taksim

Laborer Ali Sidal, 18, died in Taksim

Counterperson Kadir Balcı, 35, died in Taksim

Student Hacer İpek Saman, 24, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Kahraman Alsancak, 29, died in Taksim

Laborer Hüseyin Kırkın, 23, died in Taksim

Student Ercüment Gürkut, 26, died in Taksim

Public order police officer Nazmi Arı, 26, died in Taksim

Laborer Mahmut Atilla Özbelen, 26, died in Taksim

Factory worker Hasan Yıldırım, 31, died in Taksim

Itinerant salesperson Hamdi Toka, 35, died in Taksim

Security Guard Mehmet Ali Genç, 60, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Ziya Baki, 30, Died in Taksim

Laborer Mürtezim Oltulu, 42, Died in Taksim

Teacher Mustafa Elmas, 33, Died in Taksim

Student Sibel Açıkalın, 18, died in Taksim

Laborer Diran Nigiz, 34, died in Taksim

1 May 1977 & Impunity

'The state is implicated in this crime, perpetrators must be put on trial'

'If you can't find the killers, you can't remove the stain'

'The perpetrators of the 1 May 1977 massacre got away with it'

Remembrance as a matter of dignity and the fight against impunity

Who is hiding the truth and why?