Click to read the article in Turkish

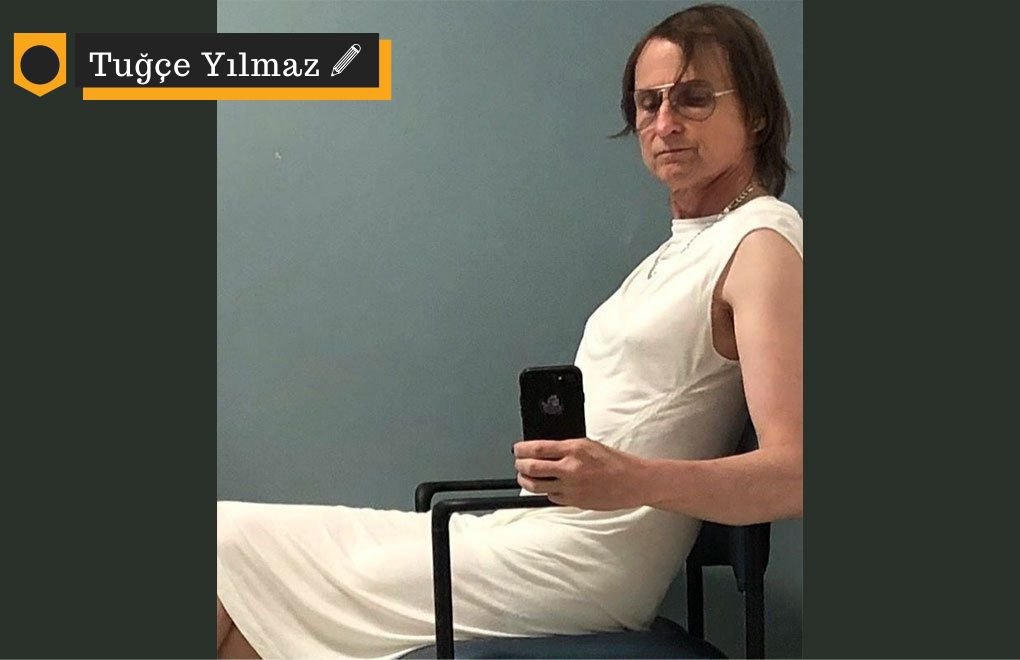

McKenzie Wark was born in 1961 in Australia's Newcastle city. She published her first theoretical articles in a post-Marxist magazine, Arena. In the 1990s, she began to write on digital media and arts.

In 2000, she was settled in the United States of America (USA) and there, together with poet John Kinsella, writer Bernard Cohen and publisher/writer Terri-Ann White, they developed a technique that they called "Speedfactory." In 2002, they jointly wrote a book on deterritorialization with the same name.

Doing an extremely interesting work again in 2002, Wark wandered with a GPS device and wrote Dispositions, an experimental work where she recorded her observations at certain times and coordinates.

Having written numerous articles and books on media theory, critical theory, music, cinema, visual arts and the Situationist International, Wark is still a professor of Media and Cultural studies at the New York New School. Also, she lectures at Eugene Lang University.

Previously, her books titled, A Hacker Manifesto (Altıkırkbeş, 2008) and The Beach Beneath the Street (Sel, 2012) were published in Turkish.

In May 2020, the author's book titled, "Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene," which she wrote in 2015, was brought into Turkish by Metis Publishing. Opening with Andrey Platonov's words, "Mother history's made monsters of the lot of us!" is a product of a long-term work of Wark.

The way the author follows in Molecular Red is as follows: The story begins with Alexander Bogdanov. According to Wark, Bogdanov, who was once a rival of Lenin for the leadership of the Bolsheviks, was trying to develop a radical knowledge and was even trying to apply it sometimes.

For the labor to organize the world, Bogdanov thought that it should develop its own organization and its own instruments of cultural development, which he called tektology. Namely, the proletkult.

Another name the author focuses on in the first part of the book is Andrey Platonov, which she also made the opening of the book with. According to Wark, it is possible to say that Platonov weaved an alternative historiography of the Soviet Union.

Likewise, approaching Platonov as a Marxist theoretician rather than a writer in the book, Wark considers him not only a theoretician who works on the labor point of view but also the comrade point of view.

In the second part of the book, "Science and Utopia," the writer's haunt is Donna Haraway, a feminist biologist whom we know for her renowned book, "A Cyborg Manifesto," which was also translated into Turkish. She takes up a significant place in the book.

According to Wark, Haraway, as Bogdanov did with tektology, builds her system by staying close to biology, releasing the metaphoric potential of the language.

Moreover, she does this by putting the "feminist point of view" against Bogdanov's labor point of view. Finally, referring to Kim Stanley Robinson, who deals with utopian practices, Wark says that Robinson, just as Haraway, approaches humans as cyborg beings that are always embedded in technoscience.

The primary purpose of the book, which can also be read as a work of restoration of honor with the names dealt with in the first part, is to reveal how these four figures, who were able to look at the past critically and creatively, can help us in the new order to be built in the future.

Insistently emphasizing that we need to build the labor perspective for the historical duties of our era, Wark says that we need to look at the Marxist theoreticians who were silenced, exiled, and sometimes convicted to death, who were deemed "unperson" in the founding years of the Soviet Union.

Thinking that this progress can only be made possible by returning to the thought systems they established and by embracing our failures, Wark, with his language that evokes novel writing, ends his book with a call for a Cyborg International. And finally, she notes: "Working of the world, untie! You have a win to the world!"

We have spoken with McKenzie Wark on her book, "Molecular Red," on what we need in the new construction in the context of Bogdanov, Platonov and Haraway, and the "Black Wave" that spread all over the world after the killing of George Floyd.

Under the title "Labor and Nature", which comprises the first part of "Molecular Red", you are analyzing two authors: Aleksandr Bogdanov and Andrey Platonov. Why did you especially prefer these two?

I'm always attracted to writers who are not considered part of the main tradition, such as Bogdanov, or whose legacy gets read very narrowly, such as Platonov. Sometimes one has to go back into the archive to find the paths not taken. Bogdanov had a unique way of thinking, within the Marxist tradition. I thought the main problem for organized labor was its relation to nature. That seemed like a very timely theme, now that we know we are in the Anthropocene. Platonov drew some inspiration from Bogdanov. He is a recognized figure in modern Russian literature, but not often read as a Marxist theorist. I think his novels can be read as an alternative history of the Soviet Union, in which the poverty of nature the power of disorganization and entropy emerge as key themes. That also seemed very timely.

Why was proletkult movement of Bogdanov, who is also pictured as "Lenin's Rival", and the institution he was trying to establish so important, and why should this movement still remain in our bag?

Bogdanov was kicked out of the party by Lenin before the revolution. He saw himself as a loyal oppositionist during it. He turned his attention to organizing culture. Proletkult was a big network in the early days of the revolution, and its mission was the self-organization of worker's culture, the creation of one that would enable workers to organize themselves. Needless to say, Lenin didn't want any rival to the party and that was shut down as well.

Could "Molecular Red" be considered as an attempt at restoring the honor of those so-called "unpersons" of the Soviet era, such as Aleksandr Bogdanov and Andrey Platonov?

We learn best from failure, I think. I'm interested in all the failed attempts to avert disaster, whether ecological, political or cultural. The first half of Molecular Red looks at the failure of what used to be called "Soviet civilization" for ways to think about the collapse we are witnessing right now, the failure of American civilization, and perhaps of its global partners and analogs.

In the second part of the book, "Science and Utopia", under the title of science you, contrary to conventional approach introduce a feminist biologist, Haraway, but not a male one. How can Haraway contribute in preparing for our journey from the theories of the past to today's Anthropocene?

Bogdanov's main work was on an alternative organization of knowledge, one in which no one process of producing knowledge was sovereign over the others. These days we have rival claims to sovereignty over all other forms of knowledge, but the leading ones are economics and engineering, or more specifically computation. In the humanities, there's a kind of will to power where we imagine what it would be like if literature or philosophy were sovereign instead. But I think we'd be better off following Boddanov's lead and asking what a comradely federation of all forms of knowledge could be like. I thought early Haraway was pointing in that direction. Like Bogdanov, but in a more up to date way, she was asking what it would be like to treat all forms of knowledge as forms of production, as labor processes. Her figure of the cyborg usefully updates what we might think that looks like. I also write about Karan Barad whose work sometimes points in that direction too. A Marxist science studies, in the spirit of Bogdanov, would be centered on knowledge production, on the labor and technics that make it. The Anthropocene seems to me to call for a different organization of labor and technics, so let's go back and see who we can read who might help with that.

In the part climatology as tectology you point to the role played by colonial occupations in recording data on climatology and there you draw attention to a very interesting situation to say, "The Second World War was a war of weather forecast." Could you open this up a bit?

Knowledge-production is always embedded in the forms of power that produce them, but what's distinctive about science is that it still produces knowledge that can be valid past the conditions of its production. Climatology – the study of climate – can only arise out of imperialism. It was empires who wanted to know where the winds blow, or why it rains where it rains and so on. The military wants an even more time-sensitive knowledge, of the weather. If you plan to attack the enemy tomorrow, you want to know if it will rain. Knowledge of climate and of weather are different things, but they are both products of a certain kind of power. The second world war is a key moment because of the scale of military activity. It drove a vast increase in the organizational power of knowledge, and in particular of computation, which is now a crucial means of production for any and all forms of knowledge.

In your book, from the very beginning, you are advocating a "more elaborate perspective of labor". How would this perspective get organized?

It's not helpful to think of the worker as ending at her or his own body. The machine is part of the worker and the worker part of the machine. One has to think laterally across the body and the tech. That's why Haraway's 'cyborg manifesto' text is so powerful. That's what it does. It seems clear that the evolution of the tech has fundamentally changed how all labor is organized. Even the most manual of labor is organized computationally.

What do we need to uncover the dark pages in the Soviet Union and to establish a new vision from the point of view of an unstandardized Marxism?

The difference between Marxists and liberals is that the liberal is eternally innocent. Someone else is always to blame for violence. To be a Marxist is to acknowledge that we've actually been in charge of organizing a sizeable chunk of the modern world and done it in ways that unleashed extraordinary amounts of violence. And still does. The biggest country in the world is still run by a Leninist party. So I think it's about looking at failures without claiming innocence. Every time Marxists in power turn to the use of surplus violence, there were Marxists who tried to stop that and proposed something else. Well, what else did they propose? They were more often than not the losers of history, so you have to return to the archive to find them.

You conclude the book by calling for the disintegration of all the ways the world is functioning by and say: we must leave the 21st century. Is it possible to weave an alternative reality in the Anthropocene age without coming down in melancholy?

Maybe melancholia would be a good thing to acknowledge. It's clear the best we can do now is mitigate the worse effects of climate disruption and (maybe) prevent a runaway greenhouse effect. But I think there's a role for utopian thinking in that what it does is seize on practical questions and really pursue them to their consequences. Utopias are not impractical, they are obsessively practical. If you think in utopian terms about what would make it possible for life to endure, that's to think practically. If you do that you notice how impractical the current civilization really is. And why we need to build a new one in the ruins as it crumbles all around us.

Finally, as far as we follow, you appear every day in the sweeping protests across the USA and all over the world what followed the murdering of George Floyd, what is your evaluation of the protest movement and the prospects?

It's good to see the focal point shift to Black lives in America (and indeed elsewhere). That's the strongest example of lives subject to the most irrational violence by what is supposedly a liberal-democratic order that likes to pride itself on defeating 'totalitarianism.' At the same time as the Soviet Union's fall, American vastly expanded its own gulags and filled them with Black people. It extended that carceral logic throughout the whole society. That there's currently a movement that makes this central, rather than secondary, can only be a good thing. It was subsidiary in the Occupy movement, or in the progressive electoral strategies of Bernie Sanders. We might finally get somewhere if we center Black lives. (TY/APA/VK)