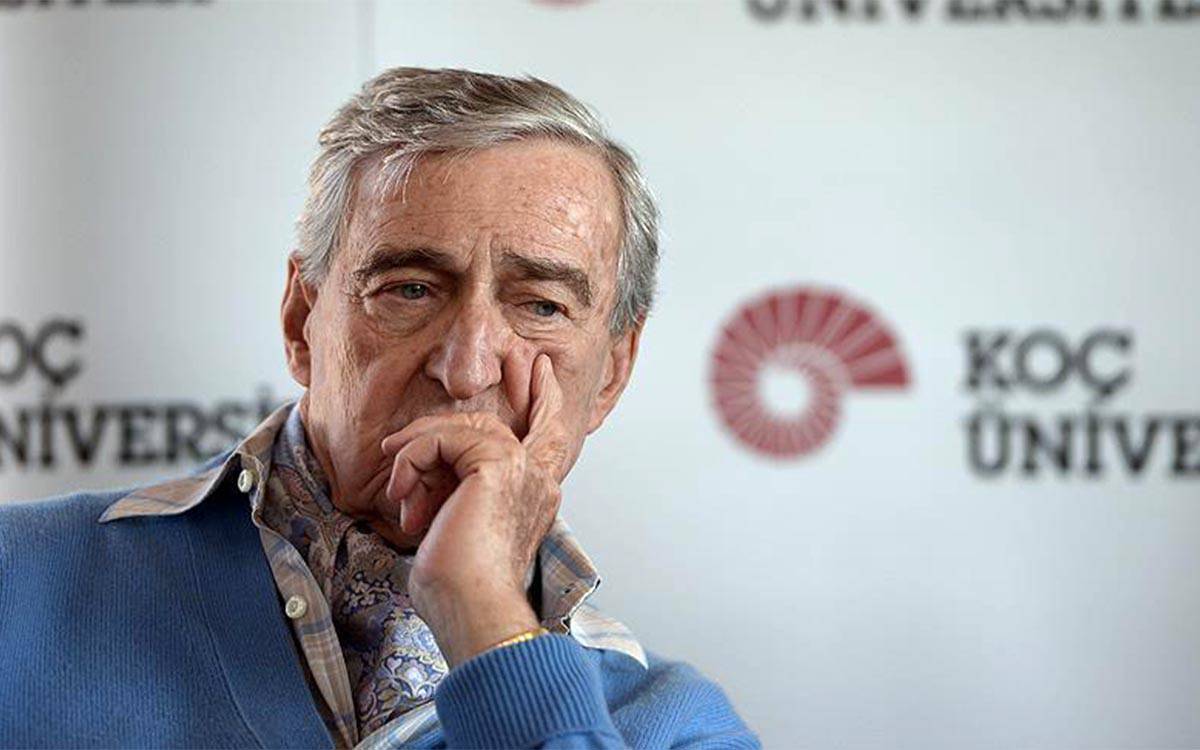

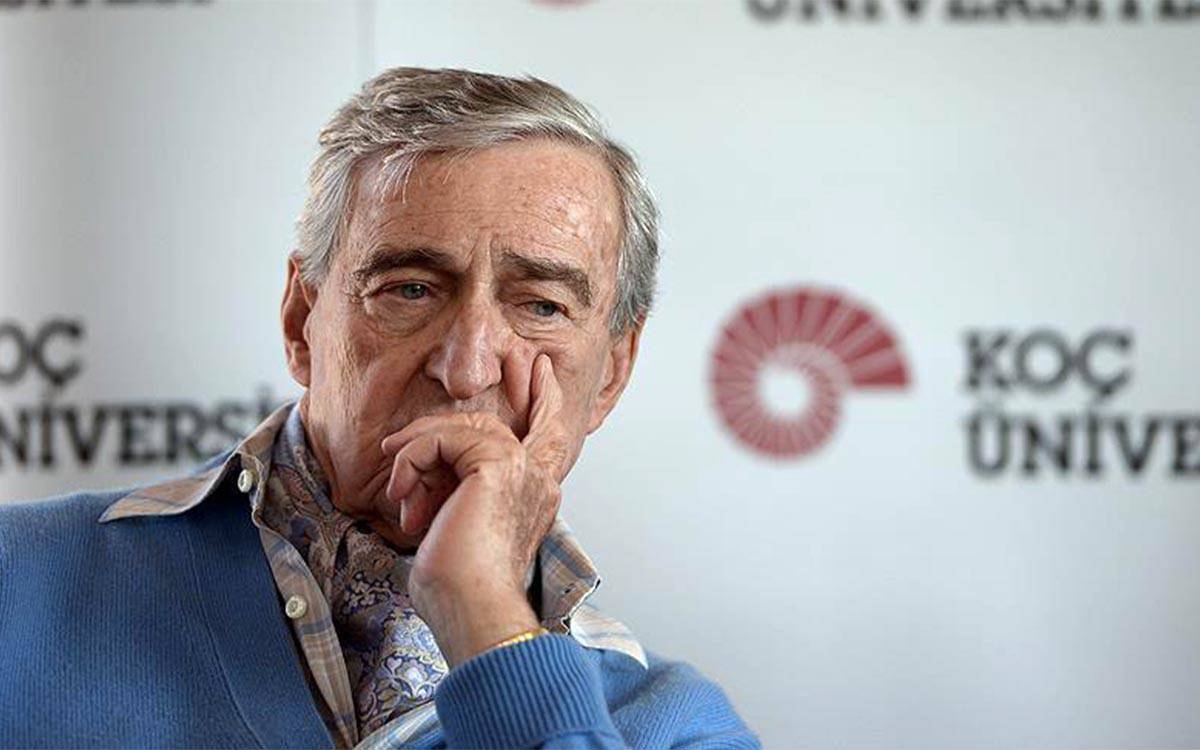

Rahmi Koç, one of the most successful and European-oriented figures in the business world, said that although 5.5 million people work in the public sector in Turkey, only 2 million would be sufficient. Like the words of other prominent figures, these sentences were disseminated through the media.

Certainly, similar statements to these are frequently echoed in all coffee shops across the country, given the widespread belief that the number of civil servants is excessive. The state is perceived as a gateway to employment for those who are seen as idle.

Since they are employees who do not have to use manual labor and do not face the risk of unemployment with a sentence coming from the boss's mouth, they are somewhat envied people. They are not particularly beloved by villagers, laborers, the unemployed, small business owners, and craftsmen. When people think of civil servants, they envision clerks in public institutions they have to visit.

Is the state a gateway to employment?

Like many popular beliefs, it is necessary to provide some figures to show that there is misinformation on this subject. Firstly, it should be noted that public employment in Turkey is not high compared to other countries; on the contrary, it is low.

According to data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the share of public employment in total employment in Turkey is 13%. In contrast, this figure reaches 18% on average in OECD countries. The countries with the highest public employment are Sweden at 29% and Denmark at 28%. The share of public employment is 21% in France, 17% in Greece, 16% in the UK, and even 15% in the United States, where the public sector is generally disliked.

There are also countries where the share of public employment is lower than in Turkey. In Switzerland, it is 10%, in Korea 8%, and in Japan 6%. Therefore, the share of public services in the country's economy is a political preference. According to political preferences, the share of the public sector can be reduced, and this is indeed happening in Turkey.

Someone needs to decide which public services will be reduced and which will continue to exist. In other words, the real political preference is the choice to be made among these public services. For this, it will be necessary to provide a few figures.

Public employment in Turkey is not around 5.5 million as claimed, but rather around 5 million people. Out of the 5 million employees, about 3.5 million are civil servants. The rest include a small number of contracted personnel and nearly 1.5 million permanent and temporary workers.

The largest groups among civil servants are education and health personnel. There are over 1 million teachers and over 1 million health personnel working in the public sector. The employment in these two fundamental areas already exceeds 2 million.

After that, the security forces come into play. The number of police officers is not very clear, with the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) giving a figure of 330,000 and Eurostat giving 475,000. This group includes 45,000 officers, 135,000 non-commissioned officers, 110,000 specialist soldiers, and corporals. Additionally, there are 55,000 village guards, but they do not have official civil servant status. It is estimated that there are also 8,000 intelligence personnel.

When we add the personnel of the Presidency of Religious Affairs, which the state deems indispensable with its 140,000 employees, and the fire brigades with 35,000 personnel that no one would argue against being mandatory, the total already reaches 3 million.

Where will the savings come from?

Where do those who advocate reducing public employment want the savings to come from? To answer this question, it is necessary to look at who wants to reduce public services. As is known, reducing public services has always been one of the top priorities of liberals.

The liberal economic understanding already requires a reduction in public services. The issue is evaluated in terms of efficiency. It is argued that the resources allocated to the public sector, believed to be inefficient, are nothing but waste. However, it is claimed that if these resources were allocated to the private sector, overall efficiency would increase, contributing more to economic growth.

This thought is internally consistent. If you believe that the market can balance everything and legitimize any situation brought about by market balance, you should also minimize public services as much as possible so that the disruptive effects of the public on the market are limited.

This is a very old way of thinking, or rather, a way of thinking that has persisted and exerted its influence over time. Non-economic additions have been made to this perspective over time. First, an identity was established between the concepts of liberal and democrat. Being liberal was presented as a prerequisite for being a democrat. The collapse of the Soviets also contributed to the popularity of this view in many places.

When the concepts of liberal and democrat became integrated, a reasoning emerged that the smaller the state, the more democratic it would be. This line of thinking gained popularity, especially for those who were weary of the pressures of the state during the period after the 1980 coup. Slogans like a small state and a small constitution became attractive.

In the recent past, with a rare social consensus, the state was downsized. There are very few public enterprises left that could not be sold. Several non-business public institutions were also closed. Public properties were sold, and specific pieces of nature were either sold or leased indefinitely. This process is not finished; it is ongoing.

Liberals still advocate for the reduction of the state, but now they no longer emphasize freedoms and democracy. Reasons such as efficiency, effectiveness, and profitability are being put forward. It has been realized through experience that reducing the state does not necessarily lead to freedom and democracy.

Reducing the state does not mean reducing the instruments of oppression of the state. What is actually desired is to reduce the public services provided by the state. This means implementing the security state that liberals want.

Who needs public services?

Do those who talk about reducing the state contemplate reducing the army, the police, the gendarmerie, and intelligence? What do they think about the personnel of the Presidency of Religious Affairs? Or are they inclined to reduce public services like education and health, which they see as expense doors due to their massive staff?

Public services are important for the middle and lower-income groups of a country. The extent and quality of these services do not concern the upper-income groups. The upper-income groups solve their health problems in private hospitals, send their children to private schools that provide quality education, do not need public transportation for their daily lives, and use private security guards to protect their homes and businesses.

A decrease in the budget allocation for public services and a reduction in the personnel to provide these services are only a problem for those segments of the population that use these services. For those who do not use these services, they are dispensable issues. Therefore, when savings are needed, public services come to mind. That's why these institutions constantly lose their quality, and public services are continuously removed from being free through various methods.

It is known that there are some business circles not satisfied with some of the government's practices. They are seen criticizing exchange policies, interest policies, and even some public investments from time to time. However, not a single criticism is brought against the continuous lowering of the quality of services like education and health. Regardless of how much disagreement they have, in the end, those who do not need public services find common ground in their stance against the state. (BD/VC/VK)