Ali Levent Sinirlioğlu was not alone in what he experienced – there were countless stories like his. Thousands of people with roots in Turkey living at the margins of German society, working hard jobs for little money and experiencing racism daily. But he was not invisible like many others. Because Ali Levent Sinirlioğlu was not a real person. It was a false identity that the investigative journalist Günter Wallraff lived under for almost three years. He wrote a book about his experiences that sparked debates across Germany. When it was published in 1985, it brought racism back into the spotlight. Germany was caught in a “wave of shock and shame”, as biographer Gottschlich writes. At that time, many Germans thought that racism belonged to the past, and that Germany was an equal country now. The German society was moved by this account of an immigrant worker’s life, and some began to question how they treated foreigners that they encountered. This is the story of a brave journalist and a book that improved German society’s treatment of foreigners – even if just a little.

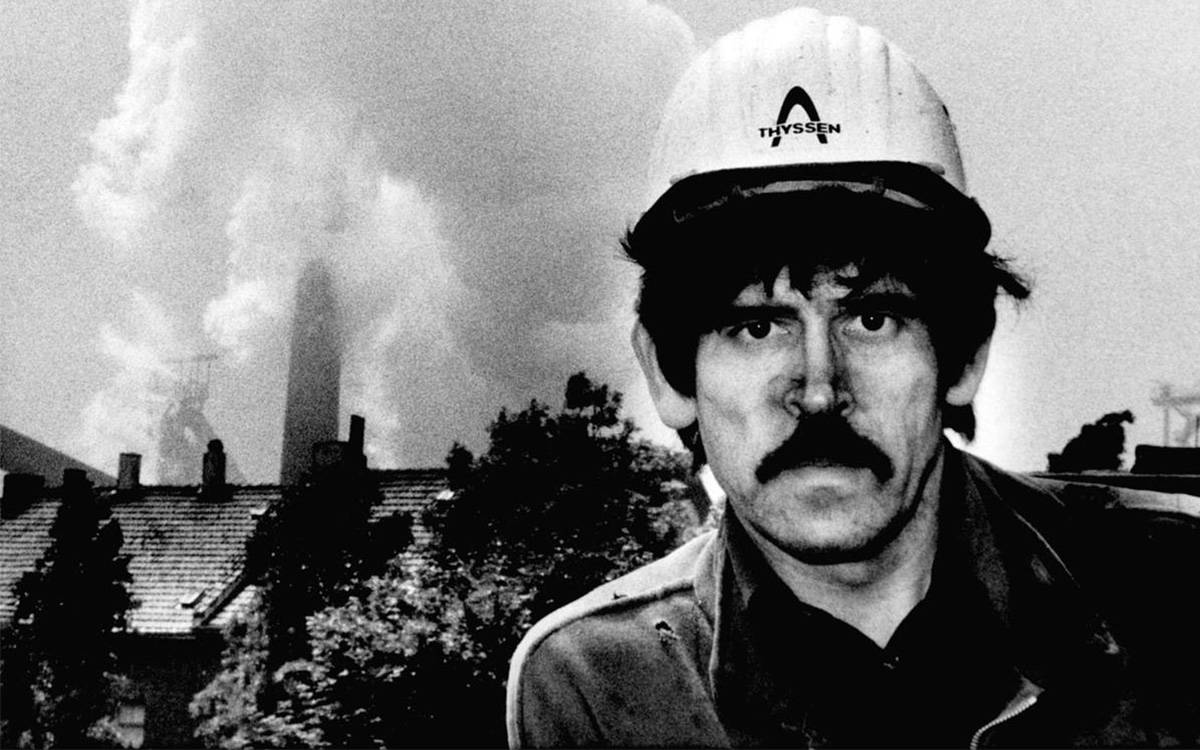

Günter Wallraff became famous in the 1960s and 70s when he published his first undercover reports. He was known for his style of research, where he took on false identities and disguise to see what he was not supposed to see. This was so successful that many companies had photos of him on their blackboard as a warning. After working in different industries, he took on the Identity of Hans Esser and started working at Bild Zeitung, the most popular newspaper in Germany, which was often criticized for its unethical journalism methods. After working there for four months, his identity was revealed, and he wrote a book about what he experienced there. Three years later, he took on the identity of Ali Levent Sinirlioğlu and started his research for what was to become his most famous book: Ganz unten, lowest of the low, or en alttakkiler in Turkish.

“Foreigner, strong, looking for work, no matter what, hard and dirty work as well, also for little money.”

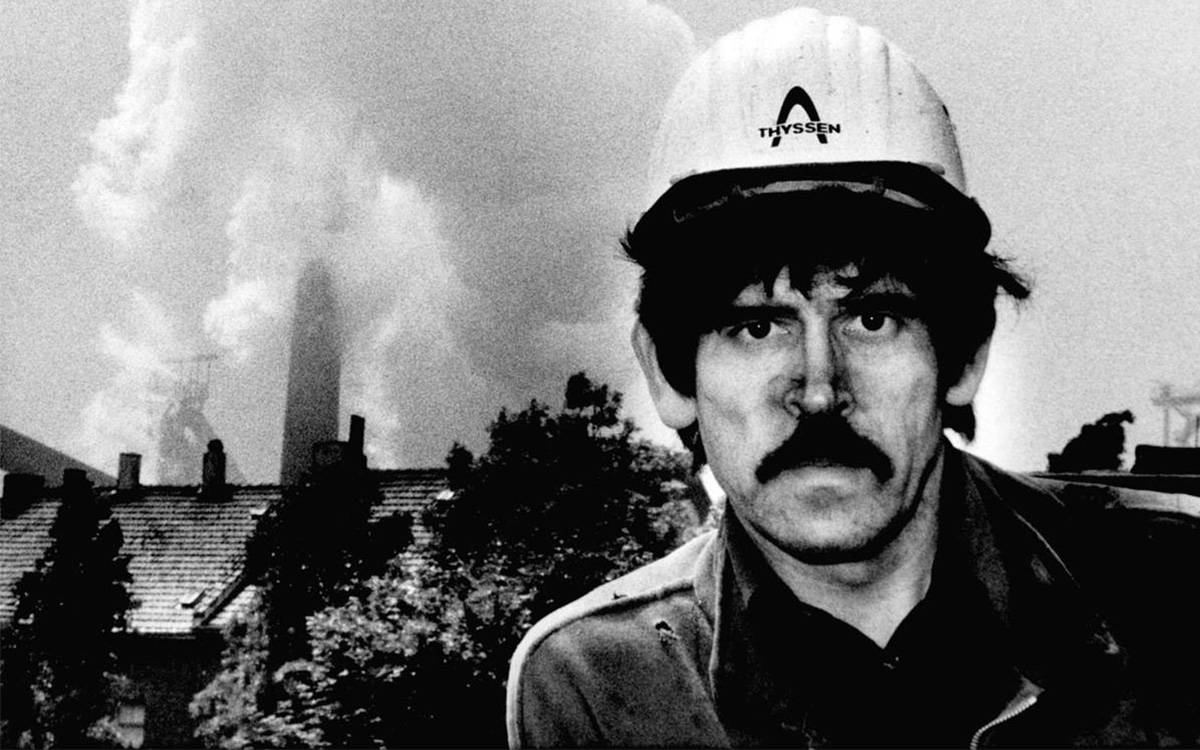

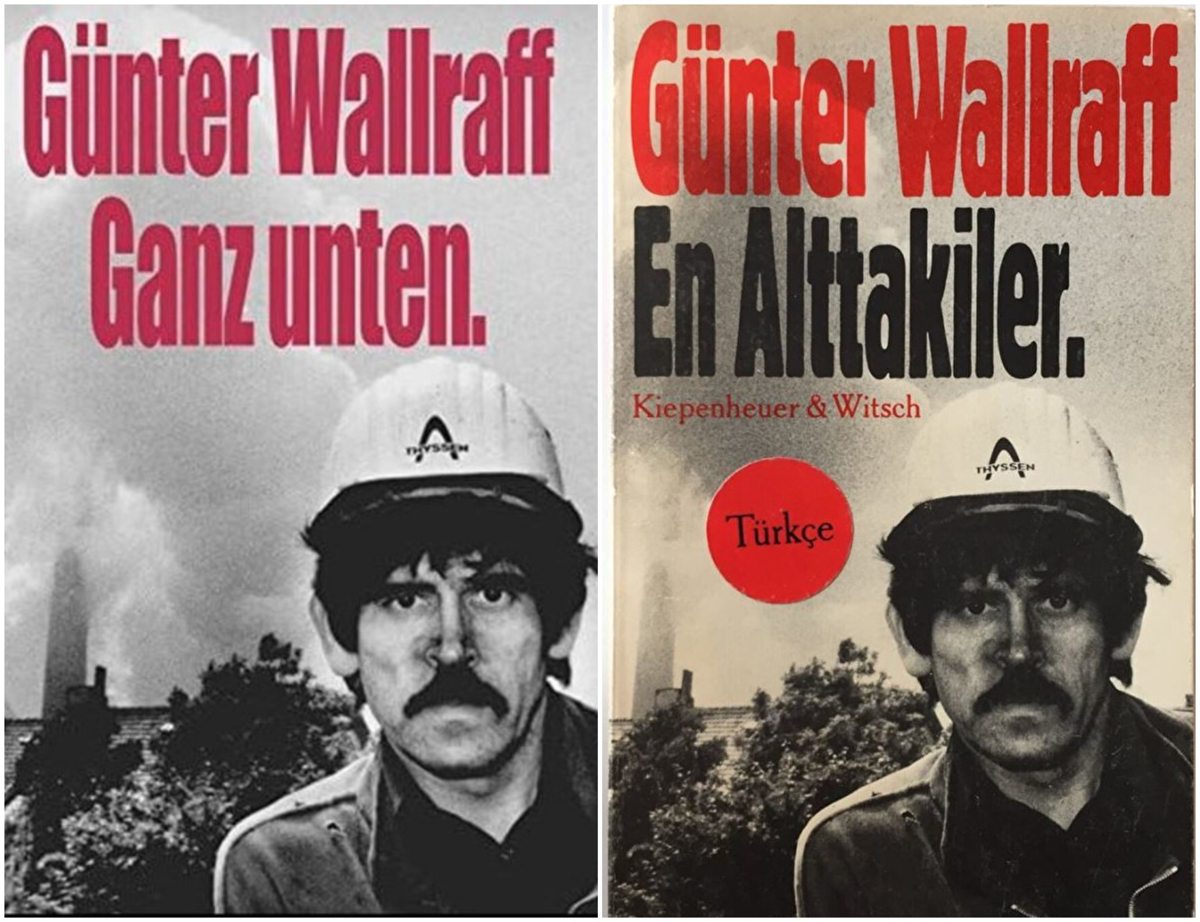

He used contact lenses and a wig in order to make himself look younger and “Turkish”. He started to talk in a stereotypical accent, sometimes skipping the last syllable of a word or using the wrong articles (German nouns can have three genders). Also, he created a story for himself: He said that his father was Kurdish and his mother Greek and that he grew up in Greece and therefore didn’t speak Turkish. After this preparation, he announced in a newspaper: “Foreigner, strong, looking for work, no matter what, hard and dirty work as well, also for little money.”

His role as an immigrant allowed him to see a side of life in Germany that he could not have seen without his masquerade. In the two and a half years that he lived as Ali, Wallraff worked at McDonald’s, on construction sites, as a test object for new medicine and at Thyssen, a huge steal factory. He was working for a sub-contracting company most of the time, which means that he received the money not from Thyssen directly but from the contractor. This practice was popular because it meant that Thyssen was not directly responsible for him and didn’t need to pay him as much as their own workers. He was assigned harsh and dangerous labor, cleaning machines from oil and toxic metallic dust. Like most of his colleagues, he developed problems in his lungs. Sometimes, he had to work 16 hours nonstop, being scheduled for another shift without prior notice. He also didn’t receive any protective gear, unlike his German colleagues, and didn’t have any health insurance. His colleagues were often insulting him and talking about the Nazi times, saying that it was better back then, and that Hitler would have known how to deal with people like him. One day, Ali went to a football match where Germany played against Turkey. He supported the German team and only cheered for German goals. Still, German fans insulted him, threw cigarettes in his hair and spilled beer over him. This was the only time he dropped his identity, because there were some Neo-Nazis in the stadium, and he thought they might hurt him. Wallraff suffered a lot during this research, but he kept going because he knew that there were people who had to work in these conditions not for two but for eight or ten years. Before he started his life as Ali, he was able to complete a marathon in less than three hours. After his research, he could barely do half an hour of jogging without having to rest.

The German society was questioning what they took for granted

In the book, he simply narrates what he experienced in these two and a half years, sometimes adding background research and sometimes even some humor. But what was shocking about the book was its immediacy. People were so surprised that all these things were happening in their time, probably even in their city. When the book was published in 1985, it was an immediate success, prompting huge discussions in Germany. It was the best-selling non-fiction book in Europe at the time and has been translated into more than 30 languages since. German politics reacted to the book by implementing stronger control mechanisms and banning sub-contracting in specific fields. But there were even bigger changes in civil society. People began to look at immigrant workers from Turkey differently.

Close to 900.000 people from Turkey came to Germany between 1960 and 1970, following a labor agreement between the two countries They often worked hard labor jobs in factories, and presented a large contribution to German industrial growth. In German, they are referred to as Gastarbeiter, meaning guest workers. In the beginning, they were expected to return to Turkey after a few years. But around 350.000 of them stayed in Germany.

Many of them were isolated, living at the margins of society, the lowest of the low, as Wallraff writes. The discussion following the book made people question this. There were debates about immigrant rights and integration. Some Germans started engaging with foreigners, which they had not done previously. The German society was questioning what they took for granted: A democratic society where all people are free and equal.

Germany is still not perfect, we still have racism and there is still no equality. In the beginning of this year, the right-wing party AfD was above 20% in surveys. After an undercover research by the investigative journalism center Correctiv revealed a secret meeting in January of right-wing politicians and entrepreneurs, who discussed “remigration”, a German right-wing term describing the ‘deportation’ of people who are not ‘integrated’ enough, even if they have German nationality. This sparked wide discussions and protests in Germany. Since then, the AfD lost more than 5% in surveys. This is why it is important that we have engaged journalists, and Günter Wallraff can be considered the father of politically engaged undercover research in Germany.

(NS/DT)