German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier’s visit to Turkey last week sparked a public debate in his country, not because of the recent local elections in Turkey or the future of bilateral relations but of the entire skewer of döner kebab that he brought along.

He brought various guests with him, including actor Adnan Maral, high-profile business manager Mustafa Tonguç and döner chef Arif Keleş with his 60 kg of frozen kebab.

During an event held at a residence owned by the German Embassy in Tarabya, an İstanbul neighborhood boasting a Bosphorus view, Steinmeier enthusiastically joined in slicing pieces of döner. This gesture was intended as a friendly nod to the Turks, utilizing döner, a culinary staple that has become a shared aspect of both countries' food cultures.

The seemingly well-intentioned gesture by the German president, however, faced criticism from Germans with roots in Turkey, a community of nearly 3 million people mostly consisting of Turks and Kurds. They argued that it perpetuates a stereotype of viewing them solely through the lens of döner restaurants, as if they are outsiders in the country.

Lawyer Seda Başay-Yıldız said on X that she was left speechless for “being reduced to döner,” reflecting the sentiments of many people from her community, who still carry wounds from decades of being excluded from society.

“Even in 2024, [Steinmeier] and his advisors can only think of döner when it comes to what they obviously associate most with people of Turkish origin. Is that really the only thing that comes to mind?” she further wrote.

Social Democrat politician Lale Akgün shared a similar sentiment to the lawyer. “While people with Turkish roots are struggling for their identity and a place in this society, the president, probably with the best intentions(!), assigns them a place in the fast-food restaurant,” she said.

Furthermore, there are also many Germans with roots in Turkey who have never been to Turkey, don’t speak Turkish and don’t have a closer relationship with döner than any other German.

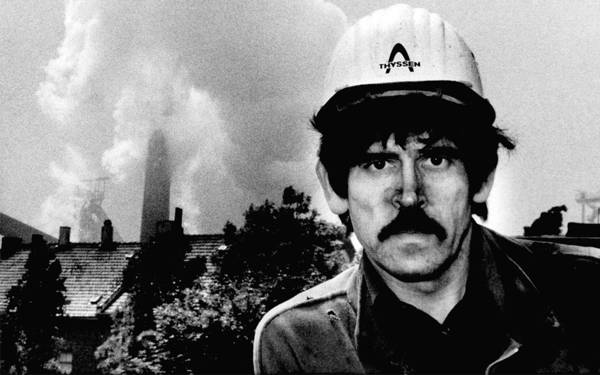

A significant portion of Germans with roots in Turkey are children and grandchildren of the first generation of the so-called Gastarbeiters, a German term for “guest workers,” referred to as gurbetçi in Turkish, which measn "expat." These people arrived in Germany during the 1960s and 1970s as part of a 1961 labor migration agreement between the two countries, often taking on hard labor jobs in factories.

German döner and döner murders

Some Turkish people in Germany developed the German version of döner kebab in the early 70s, which is served in a toasted bread and contains various salads and sauces, in contrast with the more plain Turkish version of the dish. Even in Turkey, there has been a rise in the opening of döner shops offering what is dubbed "German döner" in recent years. Döner is one of the most popular foods in Germany, with döner restaurants found on almost every street corner. This culinary phenomenon has led to a significant economic impact, with the döner industry estimated to be worth 7 billion euros.

Therefore, some people argue that döner is indeed a strong symbol for the success of Turkish immigrants in Germany and for their integration into society. Arif Keleş, the döner chef who accompanied Steinmeier in İstanbul, expressed his appreciation for being allowed on the trip. “This trip is also about the history of the Gastarbeiter. I am very glad that the president thought of us for this opportunity.” They also assert that it is a good gesture that the president doesn’t only highlight the achievements of famous actors and academics but also hard-working restaurant owners.

Döner holds a place in the expat memory not just as a symbol of goodwill but also as a reminder of a series of murders perpetrated by neo-Nazis. The “döner murders” targeted nine people with Turkish and Greek origins.

Instead of looking at the right-wing extremist scene, police had suspected that the murder must be part of the immigrant community and targeted the families and friends of the victims. The whole investigation was later found to be based on racist stereotypes.

Germans with Turkish roots don’t hate döner. But they don’t love it more than other Germans. And they may choose to open a döner restaurant, but they may also choose something else. And they are tired of being associated with döner like their path and their place are already decided for them. (NN/VK)