“Mıgırdiç Melkonyan, the son of Harutyun from the village of Garmrig in Kesgim town, Erzurum Province, was sent to the Aleppo region during the 1915 expulsion. His uncle, Serovpe Gırmanyan, is looking for him. He is reportedly staying with Arabs. Please contact Mr. Apraham Der Aprahamyan at Mehmet Paşa Han No: 8 in İstanbul…” (October 23, 1924)

“Annig Kunduracıyan, a native of Sivas, is missing. She was said to have lived in Sivas for many years before being taken from Amasya to İstanbul by a Turkish official. A reward of 10 liras will be given to anyone who can provide the official's name or relevant information by contacting K. Kantaryan at Celal Bey Han No. 27, İstanbul, either in person or by letter.” (January 18, 1920)

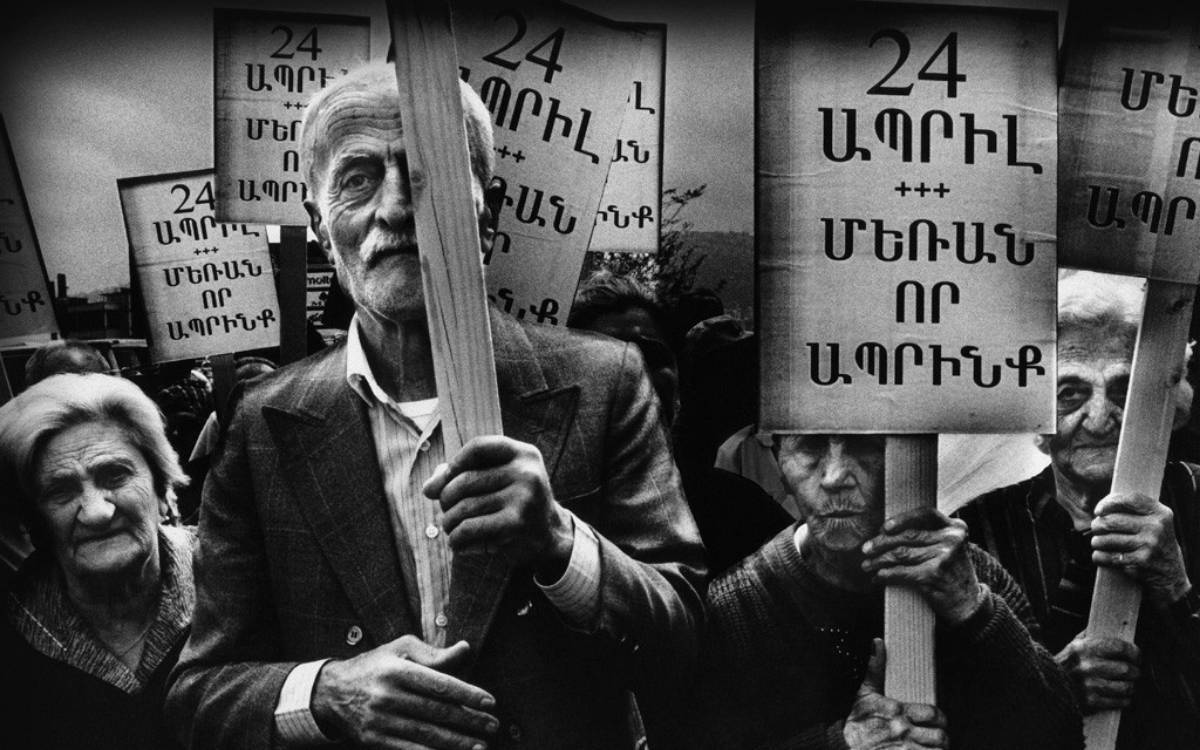

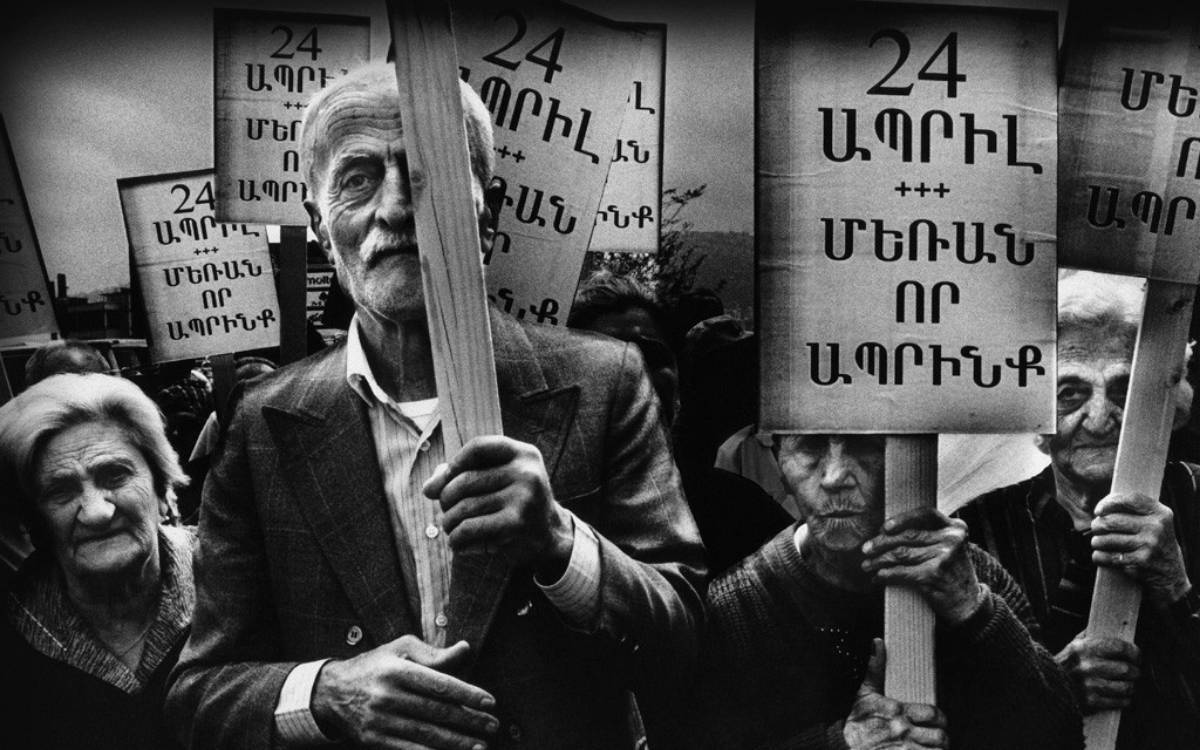

This year marks the 109th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide.

As in recent years, the İstanbul Governor's Office has once again banned the commemoration of the genocide in Kadıköy. Therefore, Armenians in Turkey could hold a large-scale remembrance for their lost loved ones.

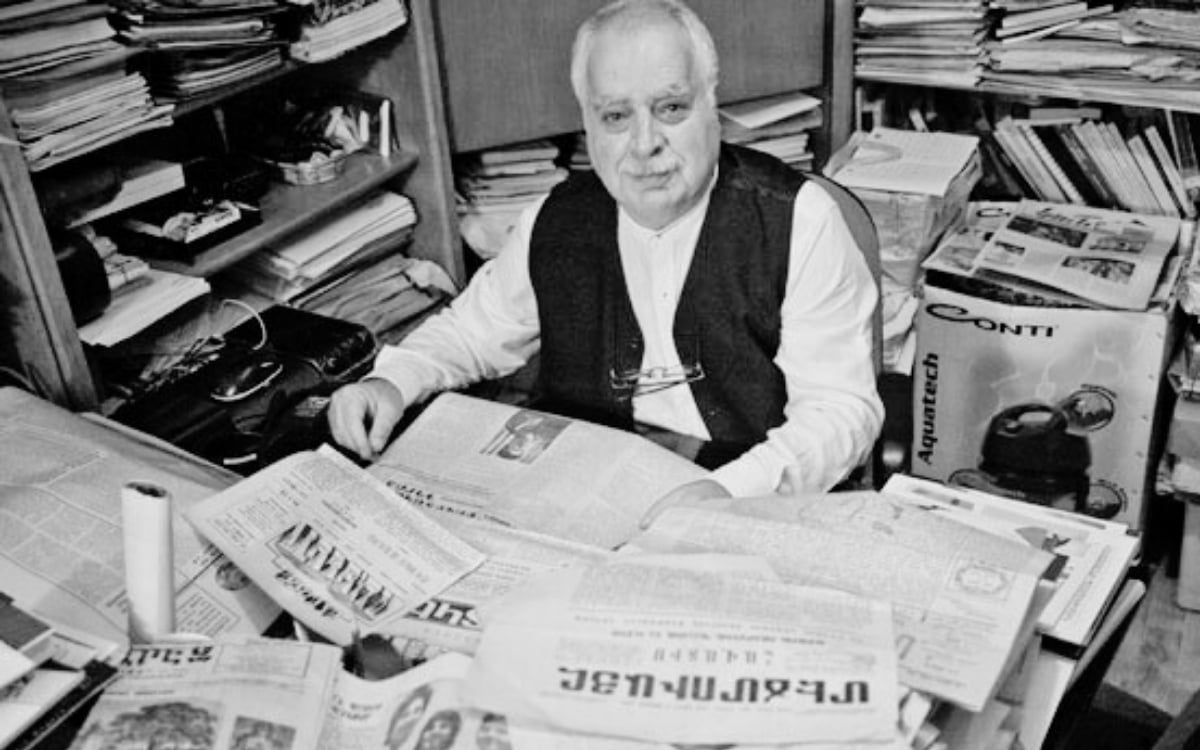

Zakarya Mildanoğlu, an architect and researcher known for his work on Armenian periodicals, has also studied the "Missing Persons" ads published in Armenian newspapers following 1915. These newspapers were first published within Ottoman borders but continued their circulation in various parts of the world.

These ads were placed by people who had lost loved ones in the genocide and had not heard from them since.

Agos, a newspaper currently published in both Armenian and Turkish, continues to share these ads free of charge, just like the periodicals of the time.

We spoke to Zakarya Mildanoğlu about his search for the "Gı pındrıvin" (Missing Persons) ads, their content, and what ultimately became of them.

Can you tell us about the "Missing Persons" ads that were published after 1915? What newspapers were they in, and who were these people searching for?

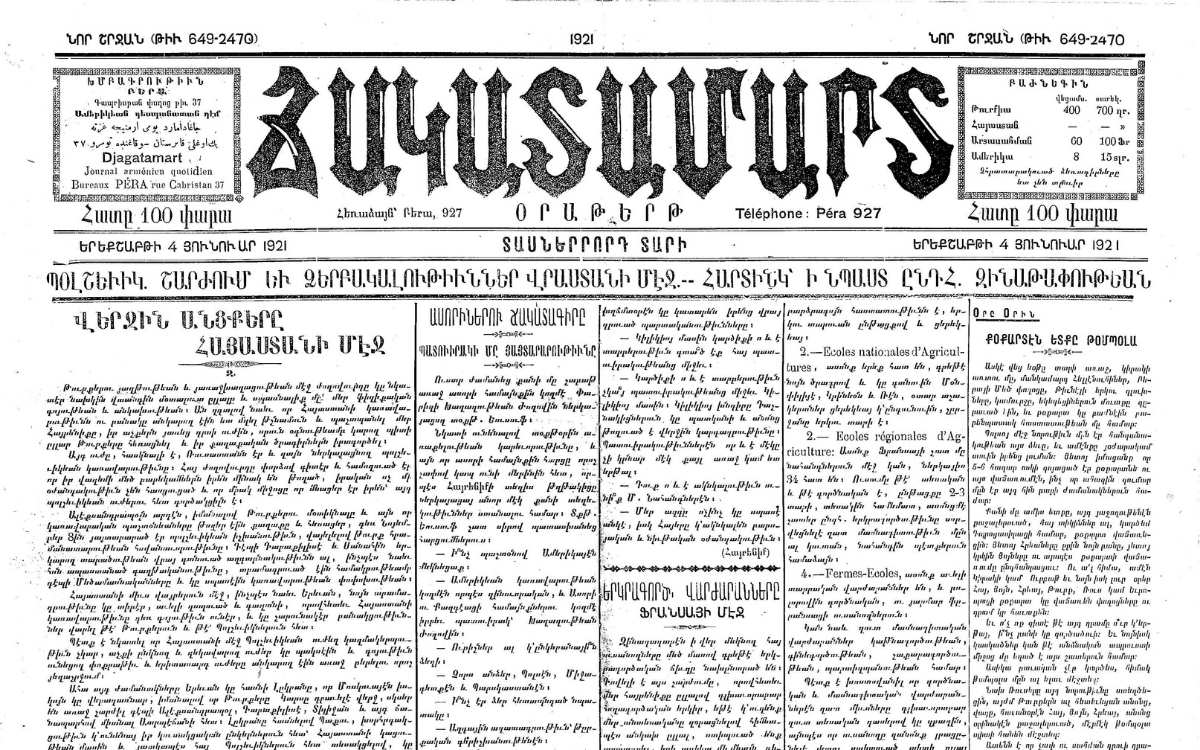

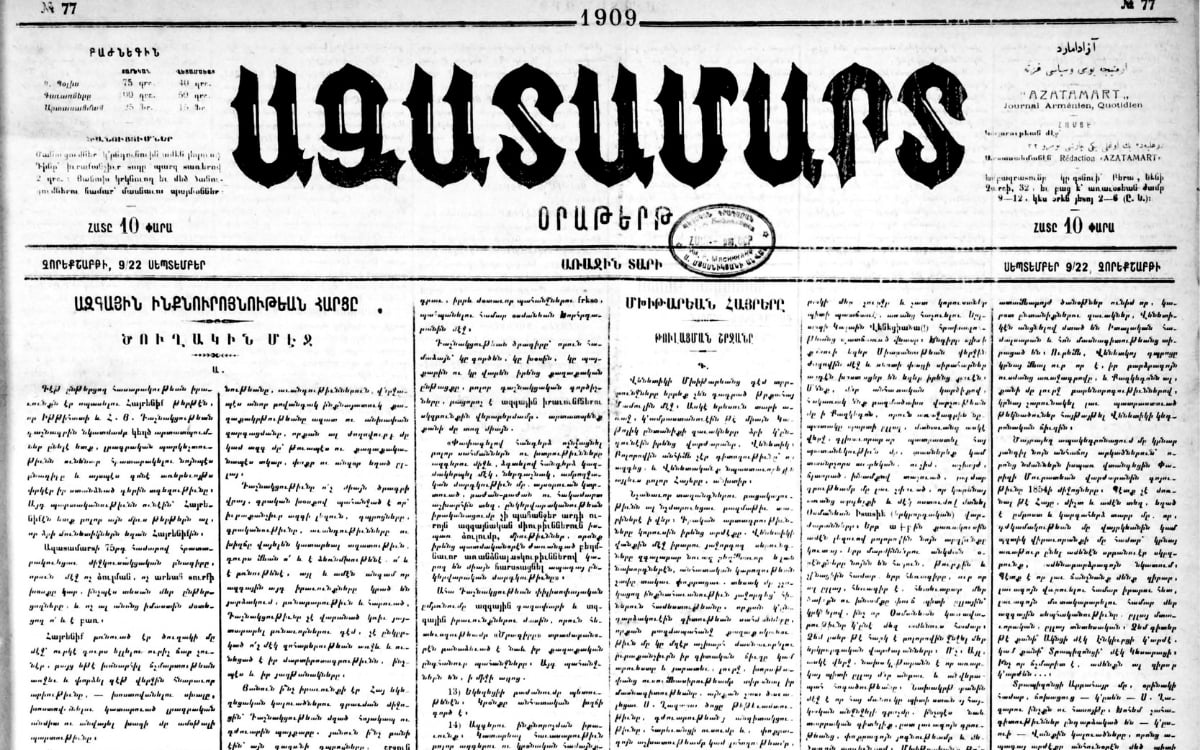

While studying the history of Armenian periodicals, I found "Gı pındrıvin" ads (meaning "missing persons" in Armenian) in the newspaper Cagadamard (Battle). This newspaper was first published in 1909 under the title Azadamard (Struggle for Freedom) and continued under different names until 1921. Its contributors and editors were notable Armenian writers, intellectuals, and politicians, many of whom were interrogated, arrested, and released before being the first to be imprisoned, exiled, or killed on April 24, 1915.

Some announcements were only a few words long, others a few lines, and some stretched to several paragraphs. It didn’t take long for me to realize that the missing persons were connected to those lost in the Armenian genocide of 1915. I scanned all issues of the newspaper I could find and categorized them by year, month, and day, then translated them into Turkish. These announcements originated in İstanbul but were soon published in cities around the world where Armenians lived.

"Kıdnıvadz"

Let me name just a few. There was Cagadamard (Battle), Azadamard (Struggle for Freedom), and Püzantiyon (Byzantium) in İstanbul; Hay Tzayn (Voice of the Armenians) in Adana; Arevelyan Mamul (Eastern Press) in Izmir; Hayrenik (Homeland) in New York; Arev (Sun) in Egypt; Alik (Wave) in Thessaloniki; Hayasdani Goçnag (Armenia’s Bell) in Boston; as well as publications in Argentina, Georgia, Syria, Lebanon, France, Bulgaria, the UK, and Italy.

Thousands of "Missing Persons" ads were published. Some were repeated for consecutive days, while others ran for months. Although rare, a few of these ads had a "Kıdnıvadz" (Found) heading. None of the newspapers charged for publishing these announcements. Some included requests like, “Please share this ad with other newspapers.” There are thousands of such ads, and reading them requires courage. Those searching or being searched for included mothers, fathers, spouses, husbands, siblings, grandchildren, children, aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces, nephews, in-laws, and friends, ranging in age from six and up.

When did these ads start being published?

They could have been published earlier, but I began reading them from newspapers printed in 1919. The ads continued for many years, albeit in decreasing numbers, until the 1950s and still appear occasionally today. Agos sometimes receives requests for publications under the title, "We are searching for our relatives." Many people who think or suspect that they have Armenian ancestry, despite their official identification showing they are Muslim, search for their loved ones.

“All newspapers went silent”

In which provinces were these ads primarily published?

Initially, the ads were published in İstanbul newspapers. After April 1915, all Armenian press ceased, and all newspapers went silent. The first victims of April 1915 were Armenian journalists, editors, writers, intellectuals, and politicians. Between 1915 and 1919, no Armenian newspapers were published except for a couple in Adana and Izmir, and these newspapers also published such ads.

These ads came from all the provinces, districts, and villages where Armenians lived. İstanbul and Izmir, supposedly spared from deportations, were no exception.

Have people been found through these ads?

Yes, some have. We occasionally see "Kıdnıvadz" (Found) ads, though there are also those that leave you speechless. Life is full of surprises, as in the case of a notice from Cagadamard dated May 26, 1921, which Kemal Yalçın mentions in his book Kardeşlerim Var Uzaklarda (I Have Siblings Far Away):

“Vahan Karagözyan of Sivas is looking for his uncle, Yesayi Karagözyan, who served as a doctor in the Turkish Army’s 4th Division under the name Şevket Bey during the World War. Please provide information to Vahan Karagözyan at Boys Orphanage A.G.R.N.G. Beyruth-Gebel.”

Who is Vahan Karagözyan? He is the person who ran away from Yesayi Karagözyan's house with his mother, saying, "We will go where our other siblings went," and was never heard from again. His story is quite long, but in 2010, ninety years later, Vahan’s cousin learned through this “Missing Persons” ad that Vahan had not died then, and efforts were made to find him.

“Twenty-five Armenian publications in Van alone”

Let’s also discuss the newspapers. In 1915, all of them ‘went silent,’ as you said. Cagadamard is considered one of the most important ones, right?

Yes, many newspapers had high circulation within the Ottoman Empire. By 1915, there were publications in various categories, reflecting the issues of Armenians both in Turkey and abroad, as well as matters of education and culture. They were published daily, weekly, or monthly and serialized novels translated into Armenian. Besides political publications by political parties, there were also publications aimed at women and youth. There were humor, medicine, law, religion, sports, health, and agriculture magazines and newspapers, some of which created a rich collection in Turkish with Armenian letters. These were published in 41 locations across modern Turkey. Just a month ago, I presented 25 Armenian newspapers and magazines from Van alone at a panel held there. The Ottoman State’s official newspaper, Takvîm-i Vekâyi, was also published in Armenian, Greek, and Arabic.

Cagadamard played an important role among Armenian periodicals. It was published in İstanbul between 1914-1915 and 1918-1924. After Azadamard was closed, Cagadamard continued its legacy. Its owner was Vırtanes Mardigyan. The editorial team included important intellectuals such as Şavarş Misakyan, Hagop Siruni, K. Mıkhitaryan, Kurken Keleryan, and Garo Kevorkyan.

Like many newspapers, Cagadamard’s publication was cut short in 1915. Most of its writers and illustrators were killed. The newspaper resumed publication in 1918, focusing on Armenian orphans and exiles and serving as a bridge between Armenians dispersed worldwide.

What would you say about Agos, which is currently one of the most important publications in Turkey?

Today, only three Armenian newspapers remain to track the Armenian community's agenda in Turkey: Jamanak (Times), Agos, and Nor Marmara.

Agos, where I volunteer as a writer, was founded in 1996 by Hrant Dink and a group of friends to highlight the issues facing Armenians in Turkey. It is published in Armenian and Turkish. Agos doesn't just address Armenians and their problems but also covers national issues. It has Turkish and Kurdish contributors and stands firmly against

One of the most important publications currently in Turkey is the Agos Newspaper. What would you like to say about Agos?

Today, only three newspapers cover and try to amplify the voices of the Armenian community in Turkey: Jamanak (Vakit), Agos, and Nor Marmara.

I contribute voluntarily as a writer for Agos, which was established in 1996 by Hrant Dink and a group of his friends to highlight the issues facing Armenians in Turkey. It is published in both Armenian and Turkish. Agos doesn't just address Armenians and their concerns but also follows the main national agenda to a limited extent. The writers include Turks and Kurds as well. The publication stands against hatred, exclusion, violence, and enmity.

Despite the financial and moral crises affecting Turkish media, Agos and other Armenian newspapers continue to persevere. Media has undergone significant changes, with most outlets transitioning to digital formats. You know this well. Our news and articles have adapted in form and structure. Agos continues to stand strong through voluntary financial and moral support. I hope it will keep publishing for a long time.

To read Zakarya Mildanoğlu's articles in Agos, click here [Turkish], and for detailed information about the newspaper's subscription system, click here.

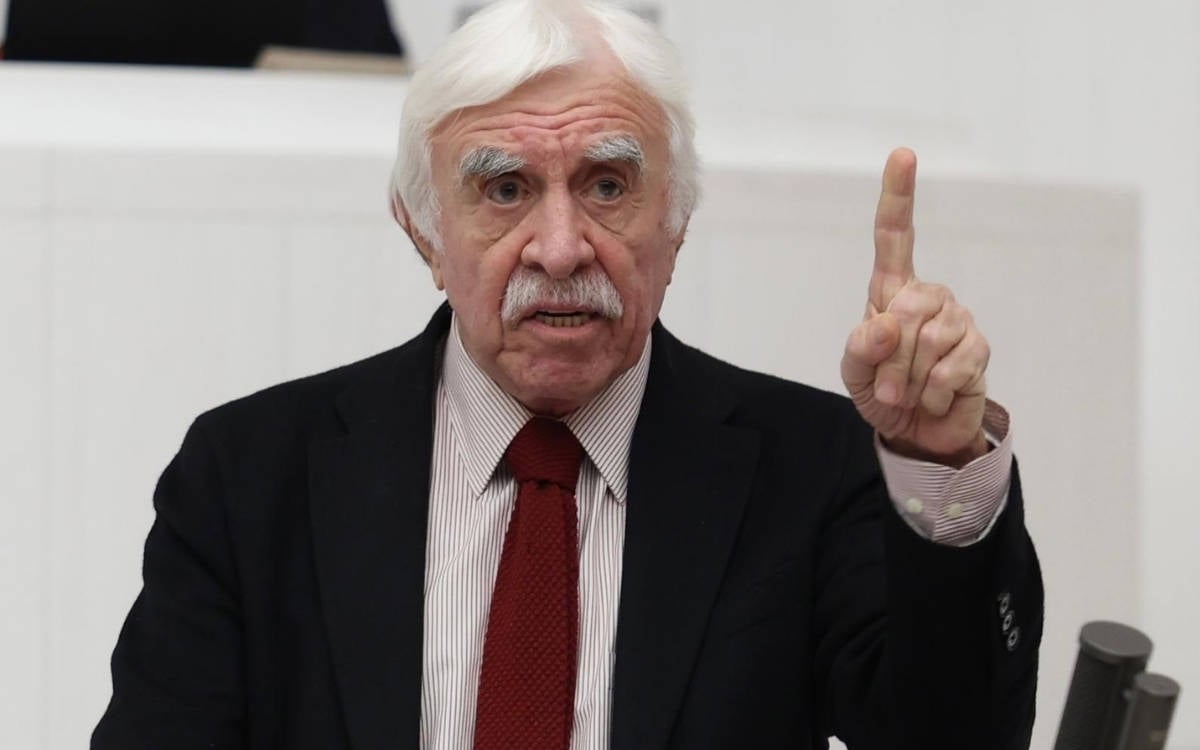

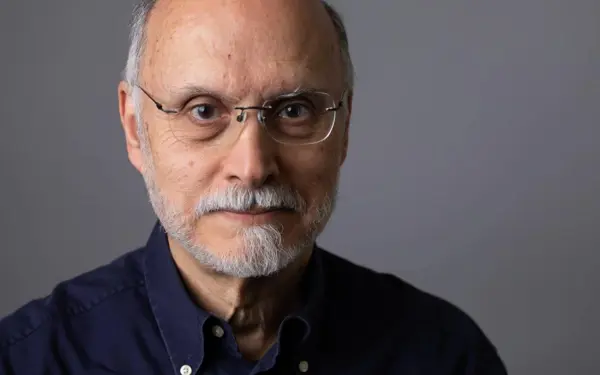

Who is Zakarya Mildanoğlu?

Berge Arabian

Berge Arabian

Architect, researcher, and writer.

He completed elementary school at the Karagözyan Orphanage in Şişli, İstanbul, and attended middle and high school at Üsküdar Surp Haç Tıbrevank School. He studied architecture at İstanbul Technical University. During his college years, he was active in youth movements and in the Turkish Workers' Party (TİP). In 1976, he joined the Turkish Communist Party (TKP). He was imprisoned for three years following the TKP İstanbul trial after the September 12, 1980, coup.

Throughout his architectural career, he led restoration projects like the Ortaköy Andonyan Union Monastery and the Beşiktaş Meryem Ana Church. As an observer for the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey, he participated in the restoration of Van Akhtamar Surp Haç Church. He received an award for the Diyarbakır Surp Giragos Church Restoration project presented at the 2012 Yerevan Biennale.

From 2008 to 2011, he wrote columns for Agos Weekly. He gave numerous talks and participated in symposia on Armenian art history, Armenian settlements in Anatolia, and the history of Armenian press in cities across Turkey, the U.S., and Europe. His long-standing work culminated in the publication of the book *Ermenice Süreli Yayınlar 1794-2000* by Aras Publishing in 2014.

He was born in 1950 in the village of Ekrek (Köprübaşı), Kayseri.

(TY/VK)