Click to read the article in Turkish

You get used to it. My world is the Bakırköy Women's Ward and Closed Penitentiary. In our town of around 1,100 women in the heart of Istanbul, and you can guess it, like a town, there are all types of people. I am not only talking about the prisoners convicted or not. There are also all types of employees, naturally.

I think there are around 150-200 workers in Bakırköy. There are few but really few men. The gendarmerie that guards the prison's entrance is primarily men, but they are not included in this number. Considering that all the convicts and inmates are women, it is no wonder that I call it a women's town.

It is possible to guess more or less who the detainees and convicts are. But who are the old guards with these old names and the prison officers with modern names?

CLICK - Gezi trial: Aggravated life sentence for Osman Kavala, 18 years in prison for seven others

CLICK - Who are the eight convicts of the Gezi case?

I will generalize, almost all of them studied at university, but barely anyone of them studied for their field of work (So far, I have encountered a total of five people who studied law or to become a warden). There are those who were not able to find work in the field of study. (Those who get 80-90 points in the KPSS exam are sifted, like in any issues in our country, these are naturally also here). They started to work as a ward at the Ministry of Justice on a contract basis. In the corridors of Bakırköy, you can find all professions, from paramedics to teachers, from dental technicians to sports trainers.

The Ministry of Justice has not been hiring correctional officers for eight years. In the last eight years, none of the prison guards got an indefinite contract. All of them work on a contract basis. When I ask, "But what about job security?" The answer is significant: "Our job security is that no one else wants to do it."

As I said, almost all of them have studied, but basically none of them studied in the field of justice or enforcement. Therefore, in prison, which is a place that really requires education, they have to deal with people and their emotions and thoughts. You guessed it right, they hardly get any training to work in a tough place like a prison.

These civil servants, who come from different disciplines, and only had an eight-week in-service training, before starting to work in, for example, Bakırköy are condemned to their observations. They have to develop their work lives with what they have learned from more experienced officers. Of course, this is difficult for every profession, but believe me, it is even more difficult in prison, where it is possible to meet people of all types, psychology, and moods.

Bakırköy prison mainly holds judicial prisoners and convicts. Most of the prisoners here are convicted or suspected of drug-related crimes; some are also addicted. And for example, prison guards are trying to deal with addiction cases.

There are around 300 non-Turkish detainees and convicts from all over the world. This comes with a language barrier. Think about living daily and keeping your head above water with those whose language you don't know and cannot understand. This is tough for both sides.

The working conditions are also not easy. In shifts, the officers work from 8.00 in the morning to 20.00 in the evening. At 8.00 and 20.00 the shifts change, which means that they come to work at 7.30 and leave around 20.30-20.45. A good guess is that a daily work shift is 13 hours.

For security reasons, they cannot leave the building they entered at 7:30 in the morning, not even for lunch. They are locked in here until 20.30. When they enter inside they are not allowed to bring their phones, they can't even bring a bottle of water.

I think most workers' lives are more difficult than convicts and prisoners. They are not allowed to bring anything in, like us, they are restricted to only taking something from the prison's canteen. Just like us, they are allowed to weekly to order from the grocery store and store fruit in the fridges of the officer's office, nowadays as much as possible...

There is a cafetaria in Bakırköy. The daily menu for the prisoners and the officers is the same. We actually have an advantage as we have fridges and a kitchen counter in our wards where we can have breakfast.

Officers who leave the house, who knows what time, to be at 07:30 in the morning in prison, mostly have to deal with the breakfast issue here. Although the law states that "the state provides three meals a day and drinking water", there is no breakfast and drinking water in Bakırköy, not for the prisoners and not for the officers.

In the morning, the officers eat whatever they can snack on. Since they are not even allowed to bring water with them, "Let's bring something healthy from home" is not possible either.

I can say that the canteen is that not really healthy either. Let's just say, the meal takes care of itself, but my main concern is that the officers do not get any fresh air for more than 12 hours. We have a 40 square meter courtyard that opens at least at 08:00 in the morning and stays open until 17:00. I honestly said to the officers, "Come and stay in that courtyard for ten minutes" from time to time! (Of course, they can't stay).

You can guess that the officers are in uniform. They wear blue uniforms. For this reason, it is forbidden to bring blue and these shades of clothing into prisons. Green is also prohibited because it is the color of the gendarmerie. Voila! Here is information just for information's sake. These uniforms, from their coats to their t-shirts to their boots, are provided by the government, of course. But how many?

One coat and one pair of boots, that's normal. But for example, T-shirts? Without air conditioning, the summers are extremely hot. You can believe spending time here in summer is tough. In clothes that are not one hundred percent cotton, living conditions are unbearable. And yes, you guessed it right, the government-issued short- and long-sleeved summer and winter officer T-shirts are 100 percent polyester. Officers are not allowed to wear anything else. They only have government-issued t-shirts.

Let's return to the start, these people come here at 7.30 and leave at 20.30. This means that if they live somewhere close, they arrive home at 21.00. How feasible is it that one can T-shirt be washed, dried, and worn the following day again? Is there no other solution possible? There is. The state sells 100 percent short sleeve T-shirts for 170 lira a piece. How many the long sleeves are, I don't know, probably 200 lira.

Speaking about money, let's talk about wages. In April, when we got arrested, the salary of contracted officers in Bakırköy was 7,100 lira. The permanent staff, who you can count on both hands, received as perhaps 1,300 liras more. With the raises in the summer, the salary of the contracted workers was somewhere in the 9 thousand, however, the increase did not make much sense as they moved to a higher tax bracket.

Remember, this year we had a very long holiday, nine days. Contracted shift workers worked non-stop for those nine days and did not receive any overtime pay for their work. Those nine days were not compensated in any way.

So how is all of this reflected in daily life in prison? Naturally, with unhappiness, despair, impatience, and anger. As I said, naturally.

You are doing one of the most unpleasant jobs in the world under such dire conditions and you don't get even a tenth of your effort. Your job is solely with people, moreover, with people whom society accepts as "bad", "criminal", and "that deserves it all".

And with these conditions, you are expected to establish a healthy prison-guard-prisoner relationship. You do not receive any training or support in this regard. You are limited by your outlook on life, your conscience, and what you know. This is, of course, terribly unfair. You cannot raise your voice against this injustice. You cannot organize. You cannot unionize, because it is forbidden.

No matter what you say, those young officers who have studied in different disciplines and dreamed of different jobs constantly take the KPSS exam, they try their luck over and over again, experience a thousand exam disgraces, they cannot be appointed again, and they are again with exam preparation books in their hands, in the prison corridors that drop below 10 degrees from time to time. They stand guard under the UFO heaters, which they were forced to install with a lot of struggle. By the way, I know Silivri is cold, but Bakırköy is also cold. Probably in also Kandıra or Xinjiang. Let's not skip those, please.

I don't want to end without saying this. We've been here for about nine months. Except for a few isolated "moments", we did not experience anything "unpleasant" in the officer-prisoner relationship. Of course, there are those that live, I'm sure of that, but not in my personal experience.

But this, one way or another, does not, of course, change the conditions and experiences of the prison guards. Hah, let me add that in the last few weeks, the most important issue here, as you can imagine, are contract rights and salary increases, like the country...

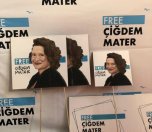

About Çiğdem Mater

Filmmaker, producer and journalist. She made documentaries, and short and full-length films. Yaban (2022 - İstanbul Film Festival National Competition), Ah Asuman (2019), Silivri'den Mektuplar [Letters From Silivri] ( 2019), Sivas (2014), Soluk (2019), Toz Bezi (2015), Sivas (2014) and Çoğunluk (2010) are among her films that received award from Turkey and abroad. She was the executive producer of international projects such as Ai Weiwei's documentary Human Flow (İnsan Seli) and Mohamed Ben Attia's Weldi. Coordinator of Caucasian programs at Anadolü Kültür (2005-2009) Coordinator of Boğaziçi University Alam Film Center (2009-2010) Turkey coordinator of the Turkey-Armenia Cinema Platform. Between 1997 and 2005, she worked as a translator, producer and reporter for international media outlets including ABC News, Boston Globe, Sky News, Radio France International, ARTE, Le Nouvel Observateur, and Los Angeles Times. She completed her undergraduate degree in cinema at Anadolu University and her master's degree in media sociology at Marmara University. |

(ÇM/APK/WM/VK)

.jpg)