"The State is by nature authoritarian; once it exists, freedom becomes impossible." — Mikhail Bakunin, God and the State

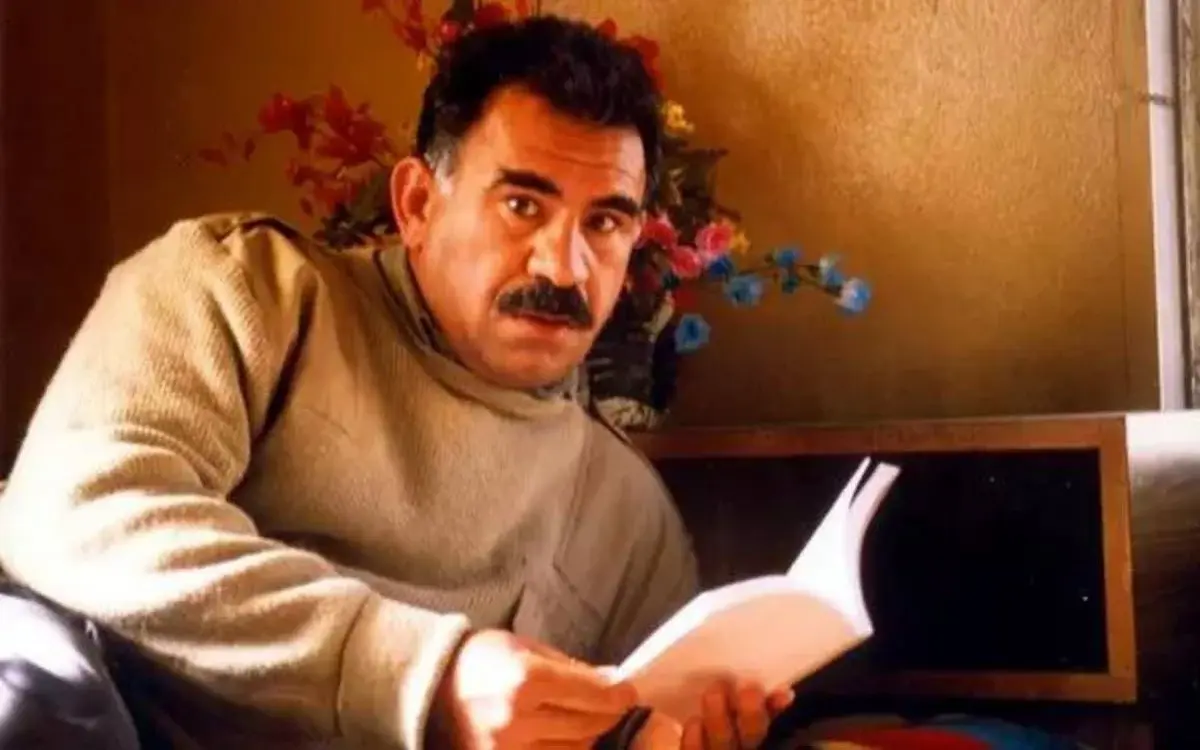

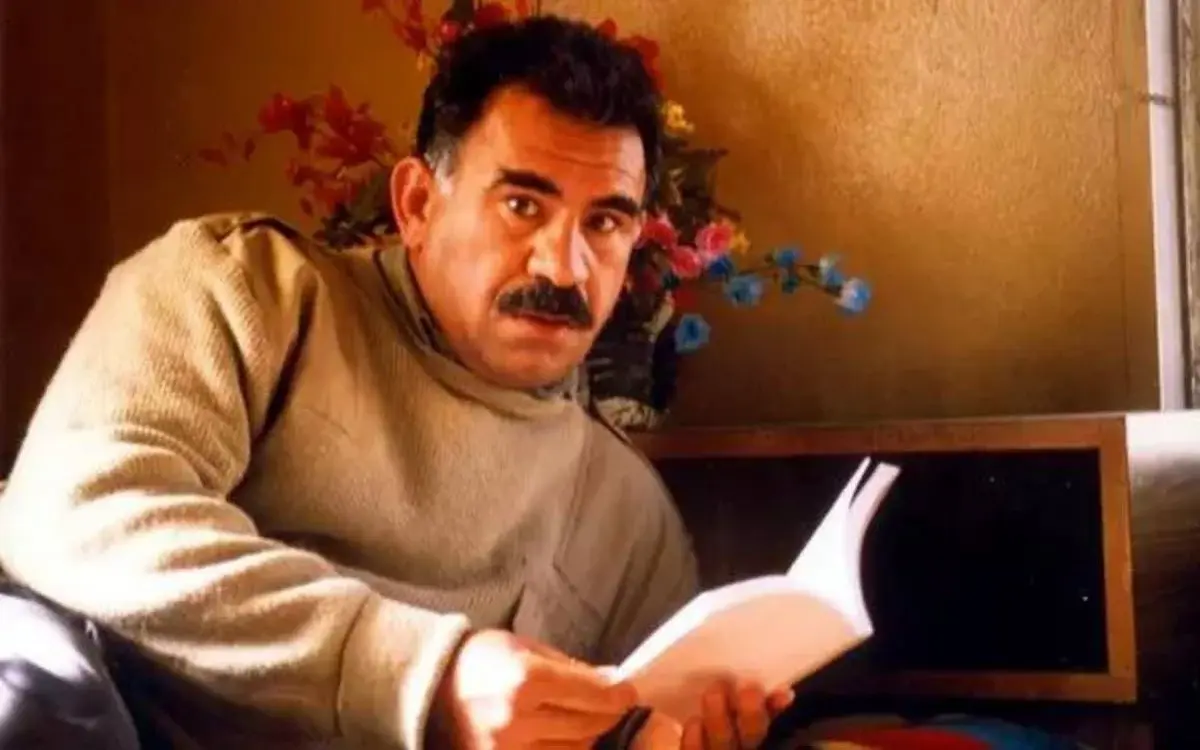

Rooted in an intellectual tradition opposed to the state and deeply critical of hierarchy and authority, anarchist theory has historically developed radical alternatives to centralized power structures and apparatuses of coercion[1]. Within this theoretical lineage, the concepts of “democratic nation” and “democratic confederalism” developed by Abdullah Öcalan in recent years are increasingly discussed within anarchist literature[2]. Öcalan’s critiques of the state, power, hierarchy, and the human-nature relationship have taken on new dimensions, particularly under the intellectual influence of Murray Bookchin[3]. This article aims to explore the intersections between Öcalan’s thought and anarchist theory, as well as the ways in which his approach diverges to carve out an original path.

In the revolutionary thought of the 19th century, the debates between contemporaries Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876) and Karl Marx (1818–1883) highlight the historical points of divergence between the anarchist and Marxist traditions[4]. While both thinkers placed the struggle against capitalist exploitation at the center of their thought, they diverged significantly in terms of method and ultimate goal. Marx argued that a workers’ state, led by the proletariat, was a historical necessity for the transition to a classless society[5]. Bakunin, on the other hand, regarded all forms of the state—whether bourgeois or proletarian—as reproducing structures of authority and domination[6]. He rejected centralism and party vanguardism, warning that even a “temporary” dictatorship of the proletariat would inevitably give rise to a new ruling class.

One of Bakunin’s primary criticisms of Marx was directed at his historical determinism and his vision of authoritarian socialism[7]. Marx’s historical materialism presented a linear model of inevitable social evolution based on the development of the productive forces, whereas Bakunin championed a more flexible and autonomous understanding of revolution, centered on human freedom and will. For him, revolution should be constructed not through a central authority, but through the direct participation of the people, via local assemblies and collective structures[8]. In this sense, Bakunin argued that Marx’s proposed revolutionary process was open to authoritarianism and would ultimately undermine the essence of socialist revolution. These debates not only marked an ideological rift between the two thinkers but also symbolized a radical opposition concerning the strategic and ethical foundations of modern revolutionary movements.

Marx 'won', Bakunin 'lost'

The conflict between Marx and Bakunin within the First International (1864–1876) culminated in Bakunin’s expulsion—along with the anarchist current he represented—at the 1872 Hague Congress[9]. This ideological and strategic conflict profoundly shaped the fate of revolutionary movements. The height of the clash came when Marx proposed relocating the International’s headquarters from London to New York—a move interpreted as an attempt to consolidate centralized leadership. At the same congress, Bakunin and his close collaborator James Guillaume were expelled on the grounds of “organizational indiscipline” and “conspiring to form a secret organization”[10].

Marx’s line laid the foundation for the Second International and later for Leninism and Soviet-style socialism. Bakunin’s vision, on the other hand, continued to live on through anarchist, autonomist, and direct action movements[11]. Following 1872, the First International was effectively split, with the anarchists organizing their own “anti-authoritarian” congress in St. Imier[12].

For Öcalan, who declared that “the state is one of the most dangerous inventions in human history; it is the crystallized form of monopoly on power”[13], the idea of a “stateless democracy” occupies a central place in his ideological transformation. This idea can be read as a re-enactment of the ideological conflict between Marx and Bakunin—this time in Rojava[14]. At The Hague, Marx defended the dictatorship of the proletariat and the central role of the party during revolutionary transition; Bakunin, by contrast, proposed a social transformation rooted in people’s assemblies, grassroots organization, and decentralized structures.

Öcalan’s radical critique of the state, along with his proposal for a horizontal and pluralistic political structure based on direct participation, revisits and revitalizes this historical debate. Particularly after 2012, the self-governance structures developed in Rojava—communes, assemblies, women’s councils, and people’s defense units—can be seen as a concrete and contemporary realization of Bakunin’s vision of stateless social organization.

Although Öcalan does not directly reference Bakunin, his paradigm resurrects the path Bakunin envisioned, in opposition to the colonial-modernist state structures of the Middle East. By exploring the possibilities of a politics beyond the state, Öcalan offers both a new theoretical framework and a practical foundation. The Rojava experience represents an effort to construct an alternative to centralized and authoritarian socialism through popular self-organization. In this way, what had long been seen as the defeated legacy of Bakunin finds renewed life in one of the most volatile regions of the world—in a social fabric composed of multi-ethnic, multilingual, and multi-faith communities. Öcalan’s paradigm can thus be understood as the reawakening of the anarchist current suppressed at The Hague, now in defiance of the colonial state formations of the Middle East[15]. (EJA/VK)

Notes

1 - Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism, HarperCollins, 1992.

2 - Thomas Jeffrey Miley, “Abdullah Öcalan and the Post-Statist Political Imagination”, Globalizations, 2022.

3 - Abdullah Öcalan, Manifesto of Democratic Civilisation, Volume 1, Aram Publications, 2009.

4 - George Woodcock, Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Penguin, 1986.

5 - Karl Marx, The Civil War in France, 1871.

6 - Mihail Bakunin, Statism and Anarchy, 1873.

7 - Paul McLaughlin, Mikhail Bakunin: The Philosophical Basis of His Anarchism, Algora, 2002.

8 - Daniel Guérin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice, Monthly Review Press, 1970.

9 - Wolfgang Eckhardt, The First Socialist Schism: Bakunin vs. Marx in the International Workingmen’s Association, PM Press, 2016.

10 - Robert Graham, We Do Not Fear Anarchy – We Invoke It, AK Press, 2015.

11 - David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004.

12 - René Berthier, Bakunin et Marx: Alliances et Ruptures, Éditions du Monde libertaire, 2009.

13 - Abdullah Öcalan, Civilisations System I: State, Aram Publications, 2001.

14 - Dilar Dirik, The Kurdish Women’s Movement: History, Theory, Practice, Pluto Press, 2022. ↩

15 - Joost Jongerden, “Rethinking Politics and Democracy in the Middle East: The Kurdish Case in Syria”, Ethnicities, 2019