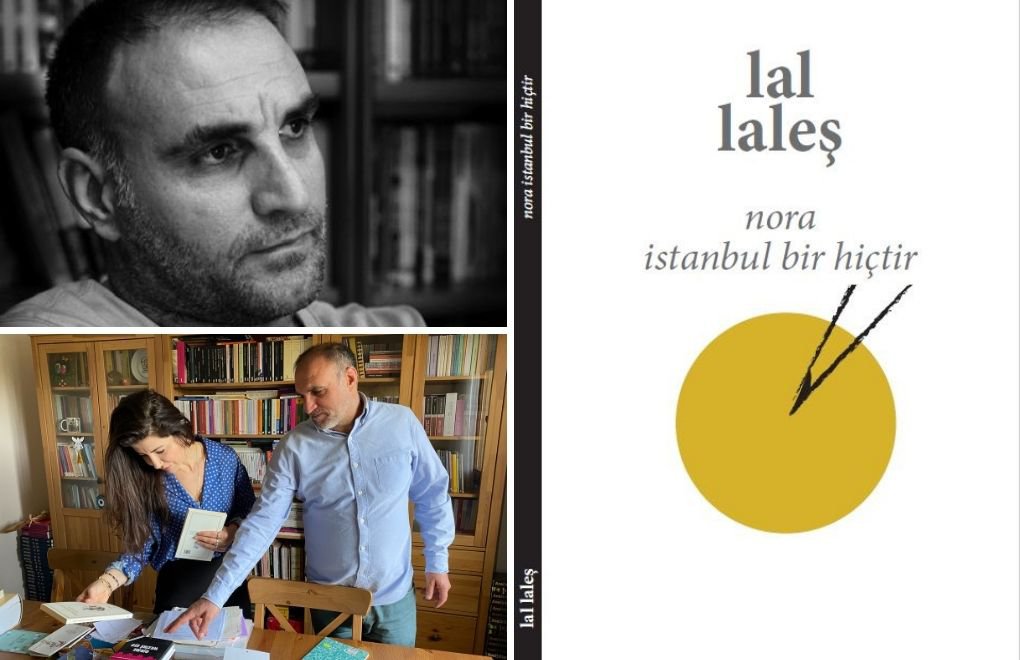

* Photo in the lower left hand corner taken by Murat Bayram during interview

Those who are familiar with the socio-cultural and political situation of Turkey's Kurds might think that the title of this article is either a rhetorical or a nonsense question. Given the lack of Kurdish language formal education, the years of bans on linguistic and cultural expression in Kurdish, the restriction on publications and narrow readership resulting from all of these in Turkey, many authors of Kurdish origin have been writing in Turkish, the colonial language. So, this is no surprise.

In fact, some authors of Kurdish origin even write very well in Turkish. For instance, ethnically Kurdish Yaşar Kemal, who died in 2015 at the age of 92, and was Turkey's first Nobel Prize nominee, wrote all his stories and novels in Turkish. He is one of Turkey's best-known authors and still remembered for his tremendous contributions to the enrichment of Turkish.

There are also many other ethnically Kurdish writers, such as Suzan Samancı and Yavuz Ekinci, who write in Turkish, but unlike Yaşar Kemal, their works do not fit into the canon of mainstream Turkish literature due to their choice of themes, cultural elements, characterization, and the political attitudes in the texts [1]. However, the works of Kurdish authors such as these cannot be grouped together with the general category of Kurdish literature either, because they write in Turkish.

The dilemma of writing in one's native language and in the language of the oppressor is still controversial in both colonial and post-colonial contexts (e.g. literature of African countries, Tibet).

The works of Kurdish authors such as Samancı and Ekinci can be considered under the category of 'minor literature' for creating new linguistic forms "within a major language" [2], which Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari define as a literature that does not come from a minor language; it is rather that which a minority constructs within a major language [3].

In this context, it can be said that those Kurdish writers in the 'minor literature' group use Turkish as a means to convey a message reflecting the 'Kurdish mind'. They could still maintain their identity or reveal traces of Kurdish culture and a way of thought in their texts even while writing in the language of the oppressor. So, the Kurdish touch is applied through Turkish in their texts, which, therefore, still represent the political (even if not the linguistic) struggle of the Kurdish literary intelligentsia.

Intolerance in politics, intolerance in public

Although the use of Kurdish in public space has been banned since the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, Prime Minister of Turkey in the 1990s, Turgut Özal, ethnically a Kurd, partially eased the prohibitions in the context of his neoliberal politics; however, much wider freedom for it to be used both in public and media outlets was granted in 2002, when the Justice and Development Party (AKP) became the ruling party.

Despite continuing restrictions on freedom, the Kurdish literary scene expanded around a growing number of writers, readers, literary journals and publishers in the cities of Kurdistan, especially Diyarbakır, who shared a strong sense of resistance to the years of prohibition and oppression of the Kurdish language.

An increasing number of Kurdish youths have become enthused to write fiction in Kurdish; likewise, Kurdish language and literature courses have become available at some universities (e.g. Mardin Artuklu University), prompting a substantial increase since 2002 in the number of Kurdish readers, though these are mostly self-taught due to lack of national education in Turkey.

Notwithstanding these liberalizations, the approach of the Turkish state to the Kurdish language has been very inconsistent, especially since 2014; for instance, Turkish authorities can still ban Kurdish language plays in both municipal and private theatres without having to provide legal justification.

This intolerance of the Kurdish language in a political context has also resulted in intolerance of the use of the Kurdish language in public. There have been several physical attacks and assaults on people speaking Kurdish in public reported in the last few years. Still, none of these grounds is enough to answer the question, why would someone who has complete mastery of written Kurdish write in the Turkish language?

But the Kurdish author I am referring to most specifically in the title is Lal Laleş, whose literary background and narratives are very different from Yaşar Kemal or those Kurdish writers grouped in the category of 'minor literature.' Why is Lal Laleş different? The answer is simple. Because he is one of the most talented, prolific and creative Kurdish literary intellectuals in Turkey.

'The text chooses the language'

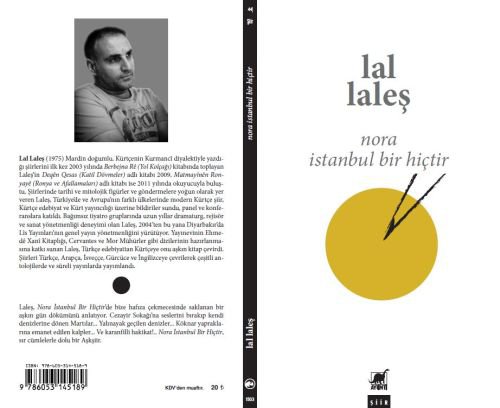

The founder of one of the biggest Kurdish publishing houses, Lîs, based in Diyarbakır, Lal Laleş has been one of the main conductors of a literary movement which promotes publishing and intellectual discourse in Kurdish, an act of protest and a weapon against socio-cultural and linguistic assimilation. He has recently published a poetry book in Turkish for the first time, entitled Nora, Istanbul is Nothing (Nora, İstanbul Bir Hiçtir). The book narrates a love story in a unified form excluding any ethnic or cultural traces.

His mastery of the Kurdish language, dozens of publications in Kurdish and, more importantly, his defence of the Kurdish language for decades both at the personal and professional level has resulted in heated discussion and even frustration amongst Kurdish intelligentsia in Turkey over his choice of the Turkish language for his latest poetry book, although not all the reactions have been negative.

Why on earth did a Kurdish publisher, author and, most importantly, Kurdish language advocate write his recent collection of poems in Turkish and get it published by a Turkish publisher rather than under his own imprint?

I put this question directly to Lal Laleş. Regardless of endless questioning by others and feeling a pressing need for self-justification, he first sighed and then answered calmly, "The authors who are bilingual do not choose the language of the text, but the text chooses the language. This book of mine, Nora, Istanbul is Nothing, has chosen Turkish for itself, not Kurdish".

His answer shows that he neither aims to subvert the imperialism of Turkish as the major language, nor his confession of his muse, which came in Turkish rather than his native language, representing a rejection of exclusionary and disjunctive logic.

He later argues that he wants to use the possibility and probability of both languages and experience both languages outside any strategy or framework. He continues, "The experience with each language is different, you get different pleasures from each language. I do not want to miss the pleasure that I get from both languages".

This short and direct answer made me question bilingualism and what it means to be bilingual. Kurds, in fact, do not see themselves as bilingual as bilingualism connotes peace and a freedom of choice as to which language a native Kurd chooses in both private and public spheres. For Kurds, Turkish has been the language of hegemony and power. Kurdish linguistic competence and the authors' political stance against Turkish assimilative language politics have determined their language choice. If one knows Kurdish and is not assimilated, then one is expected to write in Kurdish.

So, being competent but not writing in Kurdish could be seen as some sort of betrayal, as Lal Laleş' case indicates. It is interesting to note that those who are illiterate in Kurdish have more freedom in the choice of the language that they use in their literature.

'An author cannot hate a language'

At one level, Lal agrees that in the 1990s, all his hard work in supporting Kurdish literature, along with other authors and translators gathered around the Rewşen group, was intended to revive the Kurdish language, and he wrote three poetry books in Kurdish and translated a number of books written in different languages into Kurdish [4]. But he also thinks it is time to turn his face and interact with Turkish readers as his target audience this time.

He not only thinks that this interaction with Turkish readers is beneficial for their understanding of Kurdish literature, as it will make them curious to know more about Kurdish literature, but he also thinks that the Kurdish language no longer needs to be saved. He affirms, "I am not worried about the situation of the Kurdish language anymore. It will not die. The language is not responsible for the problems of the system. An author cannot hate a language. An author who hates a language cannot be an author either".

This statement is a way to assert that writing in Turkish could be considered a normalization strategy for the Kurdish language, a halt to seeing it as vulnerable, instead simply treating it as a medium for creativity and literary inspiration, like any other language [5].

He was criticized and was the target of verbal attacks on social media just because he wrote his recent book in Turkish. Despite the heated intellectual debate sparked by Lal's choice of language for his new book, it did not signify that writing in Turkish meant he was accepting the supremacy of Turkish over Kurdish, instead it meant that he owns Turkish as much as Turkish speakers own it. Lal demonstrates "the feeling of being attached to and torn between two languages that lie at his heart" [6].

More importantly, he shows that it should be possible to switch back and forth between Kurdish and Turkish, and thereby deterritorialize his literary products both in majority and native languages. He underlines the fact that this does not mean he has given up on writing in Kurdish, he will continue his works with 'Wêjegeh Amed' (Diyarbakır Literature House) in partnership with Diyarbakır Arts Centre and Literature Across Frontiers, which he founded in 2019, organising Kurdish literary events.

So, the reality is that choosing to write in a major language rather than one's native one exemplifies a personal and intellectual acknowledgement by an author of his intercultural and interlingual identity, which is both unrestrictive and fluid, and is not a contradictory literary approach.

Nora, Istanbul is Nothing should simply be seen as the piece of work which marks Lal Laleş' passing from being 'a Kurdish author' to being 'an author'. Nevertheless, his status as just 'an author' does not negate or contradict with the authenticity of his Kurdish identity. (ÖBG/SD)

About Lal LaleşHis poems in the Kurmanji dialect of Kurdish were first collected in the book Berbejna Rê (Road Armrest) in 2003; his book Deqên Qesas (Murderer Tattoos) was published in 2009 and Matmayînên Ronyayê (Ronya and her Bewilderments) was published in 2011. Making constant references to historical and mythological figures in his works, Laleş made statements on modern Kurdish poetry, Kurdish literature and Kurdish publishing, attended panel discussions and conferences in Turkey and different countries of Europe. With years-long experience in independent theater groups as a dramaturgist, stage manager and art director, Laleş has been the Editor-in-Chief of Lîs Publishing in Diyarbakır since 2004. Having contributed to Lîs' publication of Ehmedê Xanî Library, Cervantes and Purple Seals series, he has translated over 10 books from Turkish into Kurdish. His poems have been translated into Turkish, Arabic, Swedish, Georgian and English and published in various anthologies and periodicals. He was born in Mardin in 1975. About Özlem Belçim GalipShe is a research fellow at the University of Oxford School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography and works on Kurdish migrant women's activism financed by Horizon2020. She is a postdoc research fellow at the University of Oxford Department of Oriental Studies; she taught both academics and students Kurdish there. In addition to her research at the universities of the United Kingdom (Middlesex, Open, Manchester, City University of London, Oxford), she took on a series of nonacademic roles in some women's and refugee organizations, including Kurdish non-governmental organizations and Refugee Action Center. She is currently at the post-production phase of her ethnographic documentary about Kurdish intellectual women Everywhere: Letters to My Unborn Daughter and her personal journey as a Kurdish woman migrant in Turkey's Kurdish-majority provinces. The film will come out in Germany, the UK and Sweden in Fall 2021. |

[1] Suzan Samancı published one of her Kurdish books, Ew Jin û Mêrên bi Maske (The Men and Women with Masks) in 2015.

[2] Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Trans. Dana Polan. Foreword. Reda Bensmaia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1986, p.6.

[3] Ibid. 16.

[4] The Rewşen group takes its name from the journal Rewşen (Brightness, 1992-95), which was renamed Jiyana Rewşen (Bright Life, 1996-2000), and has significantly contributed to the literary achievements of Diyarbakir. Other prominent members include Lal Laleş, [5] Yaqop Tilermenî and Kawa Nemir, Rênas Jîyan.

[6] Personal interview with Lal Laleş (Diyarbakir, 8 April 2021).

[7] Perez Firmat, Gustav. Tongue Ties: Logo-Eroticism in Anglo-Hispanic Literature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, p. 4.