"Every system that draws boundaries rather than dreams for children under the name of education produces obedience, not equality; and MESEM is doing exactly that today."

Vocational Education Centers (MESEM) are presented in official discourse as “an educational model that provides equal opportunity and integrates youth into production.” However, when this discourse is examined in terms of the social function of education, it becomes clear that MESEM functions not as a tool of equalization but, on the contrary, as a mechanism that reproduces existing class inequalities. This system removes education from being a space for individual development and transforms it into a process where early and insecure labor is normalized for the lower classes.

The vast majority of students directed to MESEM are children of families with limited economic, cultural, and social capital. While children from middle and upper-class families are guided toward academic high schools and universities, children from lower-class families are pushed toward MESEM with the rhetoric of “at least they’ll have a trade.” This situation means that education ceases to be a tool for elevating individuals and instead becomes a mechanism that cements class positions.

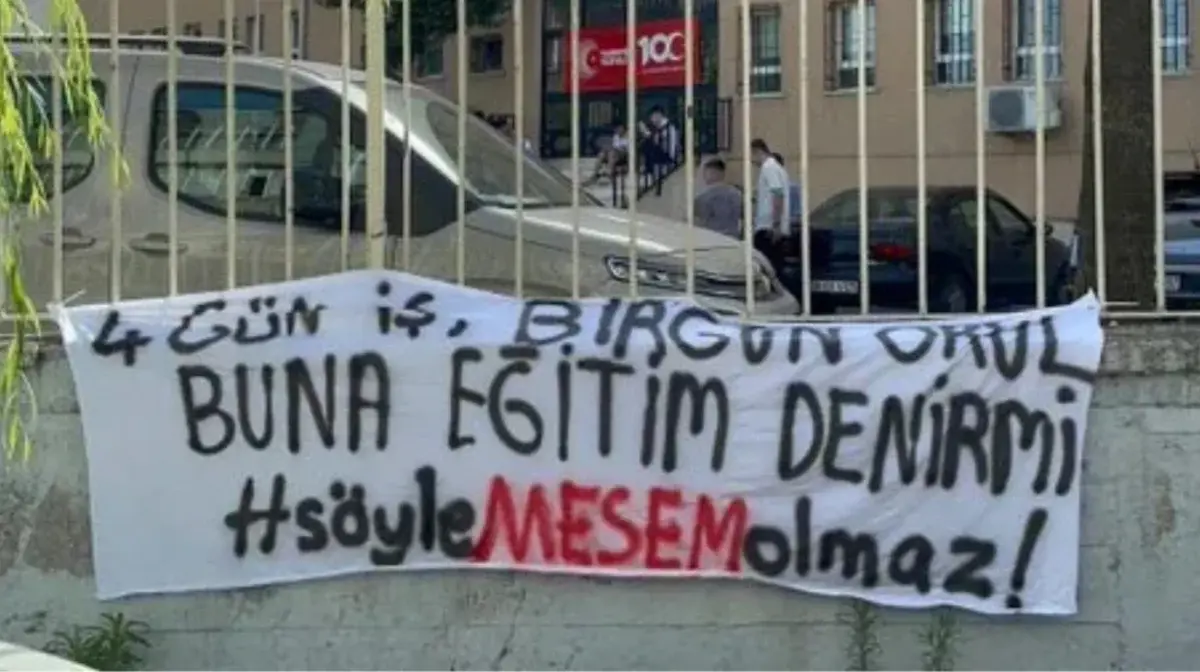

Turkey's vocational education system draws scrutiny amid child worker deaths

By pulling students into working at a very young age, MESEM instills in them not only a profession but also a sense of class destiny. For students who work four days a week and attend school for one day, education ceases to be a space for dreaming; life is reduced early on to a compulsion of “having to work.” This leads especially children from poor families to internalize social inequality.

One of the strongest defenses of MESEM is that it provides students with a salary and insurance. However, this argument is a discourse that conceals the class reality because the insurance provided under MESEM does not count toward retirement. In other words, while lower-class children spend their youth working, the long-term value of this labor is systematically ignored. This turns the concept of social security into a hollow promise.

MESEM advocates claim that the path to university remains open. Yet in practice, this path is meaningful only for the upper classes. MESEM students, who are deprived of cultural courses and lack opportunities to prepare for the exam system, are thrown into academic competition under unequal conditions. Thus, university becomes a goal that is theoretically possible but practically unreachable for the lower classes.

The phrase “not everyone can go to university” is often presented as a factual observation, but in reality, it serves only to legitimize class privilege. The issue is not whether everyone goes to university, but who is allowed to go. MESEM leaves this decision not to the student’s talent but to the economic power of their family.

Children 'exploited, killed' under the guise of vocational training in Turkey

Workshops and evaluations conducted by Eğitim-Sen on MESEM clearly reveal that this system arises not from a pedagogical need but from the needs of the neoliberal labor regime. The union defines MESEM as the institutionalization of child labor under the guise of “vocational education” and emphasizes that students’ right to education is being sacrificed to meet market demands. According to Eğitim-Sen, MESEM removes children from a qualified and holistic educational process and condemns them to insecure work at an early age, thereby deepening class inequality instead of reducing it. The most fundamental finding highlighted in the workshops is that despite being presented as an employment policy, MESEM is a structure that systematically excludes children’s academic, cultural, and personal development and positions them as “cheap labor.” In this respect, as Eğitim-Sen also underlines, MESEM functions as a mechanism that erodes the public and equalizing nature of education and reproduces class divisions through education.

Rather than producing equality through education, MESEM serves to deepen existing class divisions. While upper-class families steer their children toward knowledge, academia, and secure futures, children from lower-class families are condemned at an early age to work, insecurity, and narrow life prospects. At this point, education ceases to be a space that liberates the individual and becomes a mechanism that sends them back to the class position they were born into. MESEM, rather than building a future for youth, teaches them what kind of future they are not allowed to demand. This model, which restricts options instead of offering them and normalizes acceptance instead of generating hope, does not reduce inequality but institutionalizes and perpetuates it. Education loses its meaning unless it expands the fate of the individual. MESEM, today, stands before us as the concrete embodiment of that very loss of meaning. (AÖ/NÖ/VK)