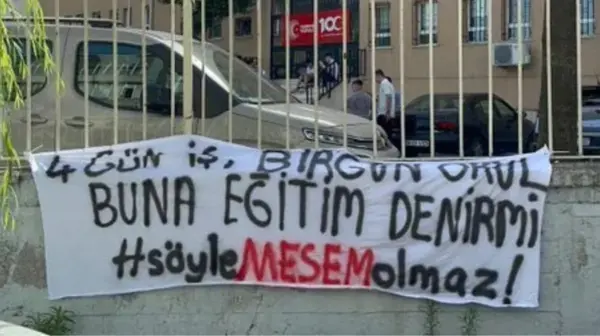

Data showing that one in three children in Turkey lives in poverty and one in five children goes to school hungry reveals a picture of not only economic inequality but also a threat to the future of the education system. A child who is not adequately nourished is directly affected in terms of learning capacity, psychological development, and sense of social belonging. Despite this, Turkey still lacks a systematic, nationwide school meal program.

Hunger widens the learning gap

Moreover, the high cost of food in school cafeterias, which is beyond the means of most families, further exacerbates children's nutritional problems and widens the gap between hunger and learning. Yet, even developing countries such as Iran, India, and Brazil have implemented school meal programs as a fundamental social policy. More importantly, in developed countries such as the UK, Finland, Sweden, and Japan, school meals are seen not only as nutrition but also as a pedagogical tool, an integral part of the educational process. Pedagogical research shows that malnourished children:

-Have shorter attention spans

-Have reduced memory capacity

-Have weakened problem-solving and creative thinking skills

-Have increased absenteeism rates

Education gains meaning through equal opportunity

Hunger directly interrupts the learning process, no matter how good a teacher's methods are in the classroom. The child's mind focuses on the biological alarm state created by hunger; it turns to survival, not knowledge. Education gains meaning through equal opportunity. However, when children from economically disadvantaged families come to school hungry, they are actually at a disadvantage even before the lesson begins. While children from middle-class families enter class having had breakfast, for poor children, starting the learning race from behind creates lasting pedagogical inequality.

At this point, school meals serve not only to satisfy physiological hunger but also to ensure social equality. School meals are not only nutrition for children, but also a place for learning together and socializing. In Finland and Japan, school meals are considered part of the curriculum; students eat together and even participate in meal preparation. This develops a sense of community, sharing, and belonging in children. In Turkey, this deficiency increases the alienation of poor children from school.

Why is the school meal program important?

The absence of school meal programs leads to short-term problems such as distraction and learning difficulties, and long-term problems such as:

Disengagement from education, increased school dropout rates, increased supply of unskilled labor in the labor market, and intergenerational transmission of poverty, causing serious pedagogical and sociological problems.

The reasons for the lack of serious efforts regarding school meals in Turkey can be examined in several dimensions:

While infrastructure investments in education are prioritized in the public budget, social support remains in the background. School meals are still seen as a “luxury” or "aid" and are not evaluated from a “rights” perspective. Education is seen as limited to teaching lessons, neglecting the child's holistic development (psychological, social, physiological). If a significant portion of children in Turkey go to school hungry, this should be addressed not only as a social state responsibility but also as a pedagogical necessity.

The school meal program should cover not only poor children but all students; thus, stigma should be prevented and the equalitarian nature of education should be strengthened. Any education policy that does not ensure the mental, social, and emotional development of children is doomed to be incomplete. Therefore, school meals should be seen not as “nutrition” but directly as the “right to learn.” (AÖ/NÖ/VK)