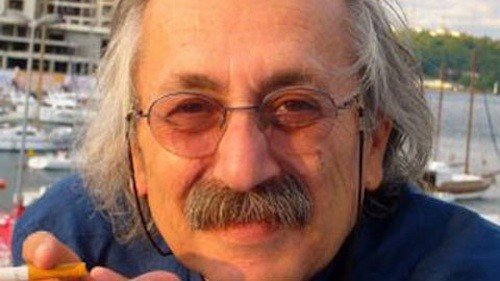

Ankara Civil Courts of First Instance decided that journalist/columnist Erbil Tuşalp and the daily newspaper Birgün should have to pay 10.000 TL as compensation due to the "Stability" (December 24, 2005) and "Get well soon" articles (May 6, 2006) of Tuşalp.

The Court considered that "there has accordingly been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention". The final judgments given in the compensation cases (nos. 32131/08 ve 41617/08) brought by the Prime Minister of Turkey, Mr. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, for protection of his personal rights constituted an interference with the applicant's right to freedom of expression, as guaranteed by Article 10 of the Convention.

According to the Court, the existence of facts can be demonstrated; the truth of value judgments is not susceptible of proof. The requirement to prove the truth of a value judgment is impossible to fulfill and infringes freedom of opinion itself, which is a fundamental part of the right secured by Article 10.

The Court mentioned that two compensation cases were brought by the Prime Minister of Turkey when the articles were published and he was and still is the Prime Minister of Turkey: "It reiterates in this connection that the limits of acceptable criticism are wider as regards a politician than as regards a private individual. Therefore, he was obliged to display a greater degree of tolerance in this context. However, the reputation of a politician, even a controversial one, must benefit from the protection afforded by the Convention.

The court decision on the form of the expressions of the author was: "As to the form of the expressions, the Court observes that the author chose to convey his strong criticisms, colored by his own political opinions and perceptions, by using a satirical style. In this connection, the Court reiterates that Article 10 is applicable not only to "information" or "ideas" that are favorably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb; such are the demands of that pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness without which there is no "democratic society".

The Court also added that offensive language may fall outside the protection of freedom of expression if it amounts to wanton denigration, for example where the sole intent of the offensive statement is to insult; but the use of vulgar phrases in itself is not decisive in the assessment of an offensive expression as it may well serve merely stylistic purposes. For the Court, 'style' constitutes part of communication as a form of expression and is as such protected together with the content of the expression. However, in the instant case, the domestic courts, in their examination of the case, omitted to set the impugned remarks within the context and the form in which they were expressed.

Consequently, the Court is of the opinion that various strong remarks contained in the articles in question and particularly those highlighted by the domestic courts could not be construed as a gratuitous personal attack against the Prime Minister, Mr Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In addition, the Court observes that there is nothing in the case file to indicate that the applicant's articles had any affect on Mr Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's political career or his professional and private life.

"In the light of the above considerations the Court finds that the domestic courts failed to establish convincingly any pressing social need for putting the Prime Minister's personality rights above the applicant's rights and the general interest in promoting the freedom of the press where issues of public interest are concerned. The Court therefore considers that in taking their decisions the domestic courts overstepped their margin of appreciation and that the judgments against the applicant were disproportionate to the legitimate aim pursued."

The fact that the proceedings were civil rather than criminal in nature - as pointed out by the Government - does not affect the Court's considerations above. In any event, the Court would point out that the amount of compensation which the applicant was ordered to pay, together with the publishing company, was significant and that such sums could deter others from criticizing public officials and limit the free flow of information and ideas. It follows that the interference with the applicant's exercise of his right to freedom of expression cannot be regarded as necessary in a democratic society for the protection of the reputation and rights of others.

European Court of Human Rights will take Tuşalp-Turkey case as precedent in similar cases. I wonder if our national law also takes the decision of the Court as precedent.

Will our courts take this case as precedent for the "judgment of dismissal" of the compensation cases that will be sued by the Prime Minister or the politicians?

Will the prosecutors declare to proceed no further by taking the decision of the court as precedent when Prime Minister or the politicians have recourse to prosecution by complaint petition?

Will the adjudicator of a criminal suit use this decision as precedent that Prime Minister registered a complaint?

In which judicial decisions, when and under which conditions the "Tuşalp-Turkey" decision will be taken as precedent? (Fİ/HK)