Tell me, Gitano, where is our land? Our mountains, our rivers, our lands, our forests, our homeland, our graves? They are where the words are, they are in our language.

It is with this sentence that the sociologist Jiménez Gonzales immerses us in the torment that has always accompanied the Romani populations, the oldest and most numerous minority in the world. We can consider them as the first "refugees" in history and therfore the most discriminated against.

In Spain, their wanderings ended under authoritarian regulations and mass persecutions. But the search for their roots is never finished. Rather, it becomes more and more relevant in a country where, like in no other, their identity is a living heritage: "In Spain, despite the persecutions - emphasizes Jiménez Gonzales - the degree of integration of Gitanos in society and in popular culture is higher than the other countries, not only in Europe, but the whole world."

In Spain, their wanderings ended under authoritarian regulations and mass persecutions. But the search for their roots is never finished. Rather, it becomes more and more relevant in a country where, like in no other, their identity is a living heritage: "In Spain, despite the persecutions - emphasizes Jiménez Gonzales - the degree of integration of Gitanos in society and in popular culture is higher than the other countries, not only in Europe, but the whole world."

Discrimination in the Iberian Peninsula persists, but in recent decades there has been a great commitment to defending the minorities. The price paid in order to reach the current level of integration was very high, starting with having to sacrifice part of their own culture. The Anglican clergyman George Borrow, who for ten years had traveled in various parts of Spain to get to know the realities in the area, had already reported it in 1830: "I doubt that there is another country where measures are enacted to suppress the name, race and way of life like those of the Gitanos."[1]

Gitano populations, in their migration process from East to West which started in the 10th century with the escape from the region that lies between the north of India and the current Pakistan, managed only from the 14th century onwards to have access in Europe. In the long journey that lasted centuries, many communities took refuge in Cappadocia, Turkey, once known as Asia Minor. This is where comes the name "Egyptian", attributed until a few decades ago to Gitanos, who were considered erroneously to be from Egypt[2].

Henceforth, their access to the west Europe takes place thanks to a safe conduct granted by Pope Sixtus V at the Council of Constance, to allow the Gitano pilgrims to visit the tomb of apostle James in Santiago de Compostela[3]. The first group of three thousan people arrived in the Iberian Peninsula iIn 1425 under the Crown of Aragon. King Alfonso V decided to extend the papal disposal and in a few decades comunities were established in the municipalities of the territory, especially in Andalusia. A honeymoon that will not last long. Dedicated to handicrafts and manual works for the nobles, the Gitanos were fascinating the people with their skill in singing and dancing. They participated in the Catholic processions of Guadalajara, Segovia and Toledo until 1478. But soon, the immense talent, the colorful costumes, and an alternative lifestyle opened the way to the prejudices.

Henceforth, their access to the west Europe takes place thanks to a safe conduct granted by Pope Sixtus V at the Council of Constance, to allow the Gitano pilgrims to visit the tomb of apostle James in Santiago de Compostela[3]. The first group of three thousan people arrived in the Iberian Peninsula iIn 1425 under the Crown of Aragon. King Alfonso V decided to extend the papal disposal and in a few decades comunities were established in the municipalities of the territory, especially in Andalusia. A honeymoon that will not last long. Dedicated to handicrafts and manual works for the nobles, the Gitanos were fascinating the people with their skill in singing and dancing. They participated in the Catholic processions of Guadalajara, Segovia and Toledo until 1478. But soon, the immense talent, the colorful costumes, and an alternative lifestyle opened the way to the prejudices.

The Catholic Church considered the practice of oriental medicine to be next to witchcraft, to be defeated with the Inquisition. While the first expulsions began in European countries, Spain was in full process of unification (1492-1517). The Catholic kings wanted to "standardize" the kingdom, and started the persecution of Jews, Muslims and Gitanos. In 1499, the "Pragmatic" law demanded that "the Egyptians no longer roam the Kingdom" and that they found a permanent job. A provision for foresaw progressive punishment, from 60 days in prison to amputation of ears, up to slavery[4].

"It is from this moment - underlines Sergio Rodríguez López-Ros, current director of the Cervantes Institute in Rome, an academic and author of the book "Gitanidad" - with the start of the repression that the Spanish Gitanos abandon their nomadic lifestyle and become sedentary communities. They work the land as laborers for the nobility. Others go to the cities to become artisans. Their historic quarters, such as Triana in Seville, El Rastro in Madrid and La Cera in Barcelona are born around the walls of access to the urban centers."

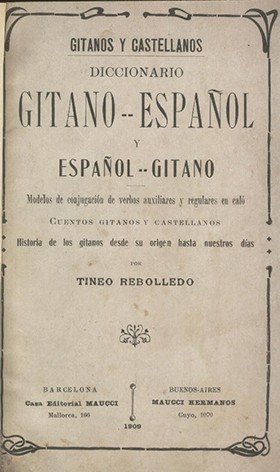

From Romani to Caló

New draconian laws, such as the prohibition of the use of Romani language and traditional clothes, were introduced in a "crescendo. All provisions bringing repression and risk of expulsion. In 1749 Fernando VI opened the way for the persecutions with mass arrests and confines at least 12 thousand people to forced labor. A loosening of controls against these communities did not come until 1783. Charles III granted them the "freedom" to work. But the language was definitively banned. "The strict regulations have led the communities to relegate the Romani language within the family and community, both as a means of cohesion and protection from the gadje, members of the social majority. Over time the language, which has Sanskrit origins – says Sergio Rodriguez – mixes with the Castilian. It is gradually replaced by caló. Today there are only a few words that come from the Romani and that are used within the Spanish grammar." The caló can not be defined as a dialect of Romani, but as an intersection of two cultures that gave birth to the neologism "pogadolecto".

For the Spanish Gitanos, the Kalé, it is a transformation set in history by the persecutions. It deprives them of the ancient language,

which despite the long migration is the common element with the other Romani communities scattered in the world. Throughout the centuries until today, this idiom has been a vehicle of both identity and self-defense, says the Gitano scholar with British origins, Ian Hanckock: "The language has been not only a tool to communicate but also a shield against persecution." To survive, the Spanish Gitanos, have had to sacrifice a part of themselves, which is now further threatened: "We, the Spanish Gitanos, speak caló – explains the sociologist Jimenez – but it is in danger of extinction. If all languages have "communication" as their basic function, it is a long time that the caló has ceased to be used in this regard. Today it serves only as a tool of identity that helps trigger the solidarity between communities." But the Castilian was not immune from the influences, either. In this language there are many words that come from the Romani, such as "chaval" which means "boy", "camelar" (want), or "jallar" (eat). Many, especially in Andalusia, are in current use, so much so that a motto of melting pot was born: "Here it is not known where a Gitano ends and where an Andalusian begins".

which despite the long migration is the common element with the other Romani communities scattered in the world. Throughout the centuries until today, this idiom has been a vehicle of both identity and self-defense, says the Gitano scholar with British origins, Ian Hanckock: "The language has been not only a tool to communicate but also a shield against persecution." To survive, the Spanish Gitanos, have had to sacrifice a part of themselves, which is now further threatened: "We, the Spanish Gitanos, speak caló – explains the sociologist Jimenez – but it is in danger of extinction. If all languages have "communication" as their basic function, it is a long time that the caló has ceased to be used in this regard. Today it serves only as a tool of identity that helps trigger the solidarity between communities." But the Castilian was not immune from the influences, either. In this language there are many words that come from the Romani, such as "chaval" which means "boy", "camelar" (want), or "jallar" (eat). Many, especially in Andalusia, are in current use, so much so that a motto of melting pot was born: "Here it is not known where a Gitano ends and where an Andalusian begins".

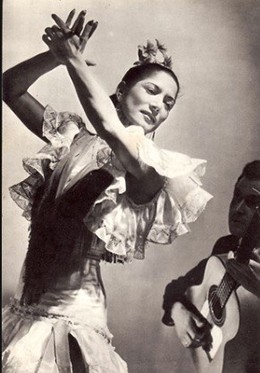

The Gitano flamenco

In addition to the language, music and flamenco have also helped Gitanos penetrate into Spanish society. The first examples ofcafé chantant in Andalusia, in the 1850s, became the stage for the artists, who until then were forced to hide underground. Through art, in an aesthetic that blends improvisation and movement, the world of the Kalé found a space in Spanish society, thanks to sensational figures like the bailaora Carmen Amaya[5]. "When we, th Gitanos, sing flamenco - says the artist Tomás de Perrate - we are doing much more than just music. We pass our culture orally." More dramatic is the feeling transmitted by a legend of the Andalusian flamenco, Tia Anica la Pirañaca from the city of Jerez. When asked what drove her to that painful lamentation, she replied: "The moment I feel the pleasure of singing, I feel the taste of blood in my mouth."[6]

But although the art is able to bring these communities closer to the rest of Spanish society, the path to integration is still long and bumpy. Especially because, despite the progress, faced with the industrialization of the countryside in the middle of 1950s, the Gitano communities were forced to migrate to the big cities, remaining on the margins of the production system. The peripheral districts where they settled became "ghettos", the opportunities for the inhabitants increasingly limited and the structure of the traditional family is altered by the phenomena of drugs and deviance.

The associationism in defense of the Romani communities

The associationism in defense of the Romani communities

It is in this alarming condition that, thanks also to the efforts of some sectors of the Catholic Church, have emerged the first structures in defense of the Gitanos. A new collective consciousness spreads among the younger generation. "We have to train mediators, develop teaching materials, create our media and fight to become part of the institutions" warned even back then the psychologist Domingo Jiménez.

Thus was born the Gitanes Secretariat of Barcelona in 1965, which in collaboration with fifteen dioceses, inaugurates a series of projects of social intervention and public awareness to spread knowledge and respect for their culture.

References that institutionalized the discrimination against Gitanos were eliminated from the 1978 Constitution. The Franco regime had returned to a heavy persecution. In addition to preventing the use of calò, it had introduced two laws against the communities considered "criminals" accused of "social dangerousness" and "nomadism".

But at the end of the Franco regime, with the introduction in the Constitution of the article on freedom of association, new organizations such as the Gitanos Association of Valencia and the Romani Union were born.

The government designed a development program for the Gitano in 1985, providing subventions. At the political level the autonomous parliaments, such as the Catalan Parliament, approved a resolution which recognizes "the identity of the Gitano people and the value of its culture". "Now they participate directly in political life - says Sergio Rodriguez. And all parties include the Gitano question in their electoral program. Transversely there are structures within institutions, such as the Ministry of Culture, to hear their voices."

Among the first to dedicate himself/herself to the political struggle for improving the condition of the Gitanos people there was definitely Juan de Dios Ramírez-Heredia, member of the Spanish Parliament from 1977 to 1985, and of the European Parliament later until becoming the president of the Romani Union.

But centuries of prejudice can not be overcome in a few decades, and many anti-Gitano stereotypes still influence the lives of these communities who hardly see their fundamental rights and their cultural differences and specificities respected.

The number of Gitanos in Spain are about 750.000 and they are still socially excluded and marginalized[7].

According to the complaints of the Romani organizations, 60% of young people aged over 16 years are illiterate. The occupational conditions are very grave too, with 36% of the Gitanos population unemployed. A problem that is becoming chronic, given that in the last ten years the unemployment rate has tripled and seasonal jobs have virtually disappeared.

"The tools to combat discrimination have improved in the last 10 years but the discrimination has not diminished – explains Sara Giménez, from the Gitano Secretariat Foundation – Gitanos are denied services, access to employment, housing and education."In the last year, 151 cases of discrimination year were registered. "There are circumstances in which there is everyday rejection which often crosses into aggression, violence, racist protest or attacks on the homes."[8] A large part of the responsibility lies in the means of communication (32%), which spread and feed anti-Gitanos stereotypes. On social networks and the internet (19%) "discrimination is turning into incitement to hatred". In the world of work there are 22 cases, reported by Secretariato Gitano Foundation (FSG), of people who were denied work because of being part of this minority. Many, according to some associations, avoid reporting the cases.

The economic situation of many communities that have been hit further by the crisis is also difficult[9]. Today, three out of four citizens of Romani ethnicity in Spain live below the poverty line and 54% of the Gitanos population is in extreme poverty. Among them are many communities, consisting approximately of 40 thousand people, who arrived from Eastern Europe in recent years, particularly from Romania and Bulgaria. Escaping from a continuosly growing racism, they have sought refuge in the "Spanish model".

Translated from Italian by Övgü Pınar

Click here for the details of Babelmed Project "R.O.M. Rights of Minorities "

1 - From the book “Los Zincali, Los gitanos en España” by George Borrow, published in 1841 and now available in 2000 edition form Portada Editorial.

2 - From the book “Gitanitad, otramanera de ver el mundo” by Sergio Rodríguez López-Ros, Kairos Edizioni, 2011.

3- Starkie W. (2010) El camino a Santiago.Las peregrinaciones al sepulcro del apóstol. Ed. Cálamo, Palencia.

4 - “Los gitanos, seissiglosdiscriminados” by Ramon Chao, Le Monde Diplomatique, Aprile 2012.

5 - From the book “Carmen Amaya 1963. Taranta. Agosto. Luto. Ausencia”, with the text by Ana Maria Mox, foto by Colitai Julio Ubiña, EditorialeLibros del Silencio. 2013.

6 - El Pais, “Murió a los 88 añosTíaAnica la Piriñaca”, 6 November 1987.

7- Source: Gitano Segretariato Foundation, from El Pais “750.000 maneras de sergitano” , 2 September 2013.

8 - El Mundo,“Las mayoresdiscriminaciones a la comunidadgitana se dan en prensa y empleo”, 4 February 2015.

9 - PNUD. The Health Situation of the Roma Communities.Analysis of the Data from the UNDP/World Bank/EU Regional Roma Survey.http://issuu.com/undp_in_europe_cis/docs/health_web#