"Real socialism, rather than solving the problem of freedom, often turned into a mechanism of power that deepened it. Systems established in the name of the dictatorship of the proletariat reinforced the domination of bureaucratic classes rather than enabling genuine self-governance." — Abdullah Öcalan

The 1917 October Revolution in Russia marked a historical turning point for the transformation of Marxist socialism into a concrete practice of state power. However, it also signaled the suppression of anarchism’s role within the revolution. Though initially claiming to represent the people's will through workers’ soviets and peasants’ councils, the Bolshevik-led revolution soon brought these structures under the absolute control of the party [1].

Lenin and later Trotsky’s theoretical and practical orientation was based on a strategy of centralizing the revolution through a vanguard party. This shifted revolutionary initiative from the people to the party apparatus. Although anarchists—particularly in Ukraine through Nestor Makhno’s movement—played a fundamental role in the revolutionary struggle, they were suppressed by the Bolsheviks, especially after events such as the bloody repression of the Kronstadt Uprising in 1921 [2].

This process of elimination laid the groundwork for Marx’s notion of the “transitional state” to evolve into an authoritarian and centralized apparatus in real socialist practice. In the Soviet Union, the state became a structure that held power in the name of the proletariat, reproducing a bureaucratic caste. The principles defended by anarchists—self-governance, decentralization, and direct democracy—were systematically crushed [3].

Between 1918 and 1921, the Red Army suppressed the free territories in Ukraine, dismantled Makhno's forces, and either executed or exiled many anarchist leaders. At the same time, anarchist collectives in Moscow and Petrograd were disbanded, their publications closed, and mass arrests and executions took place. In the name of revolutionary unity, the Bolsheviks eliminated every pluralist revolutionary actor and monopolized power, thereby systematically purging the anarchist presence from the revolution [4]. These developments led anarchists to characterize the Bolshevik regime as a “counter-revolution in the name of revolution.”

Thus, the anarchist tradition was largely excluded from 20th-century socialist movements, while the Marxist line evolved into a political reality that legitimized the continuity of the state. Yet Bakunin’s warning that “the new state established in the name of revolution will merely be a refined version of the old tyranny” was historically validated in the Soviet experience[5]. For future generations, this experience became not only a case of authoritarian degeneration but also a vital historical lesson showing why anarchist principles must be defended in revolutionary processes.

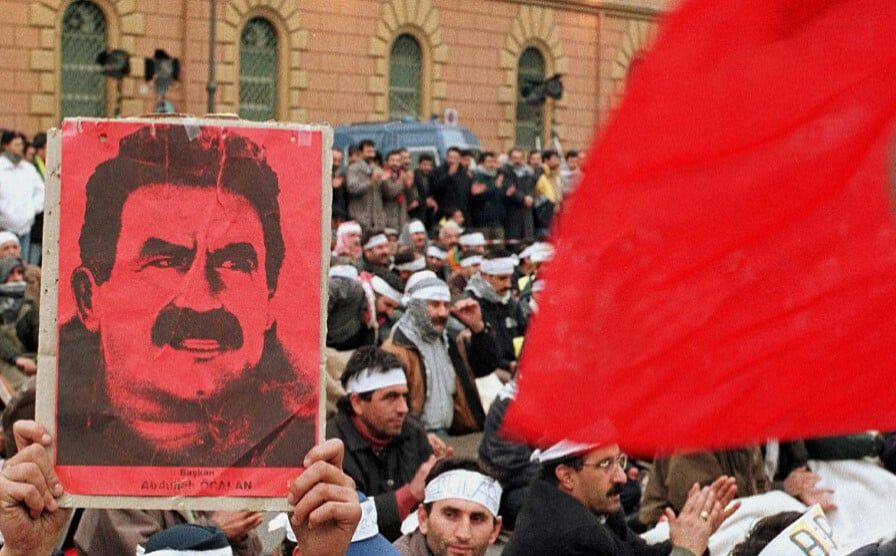

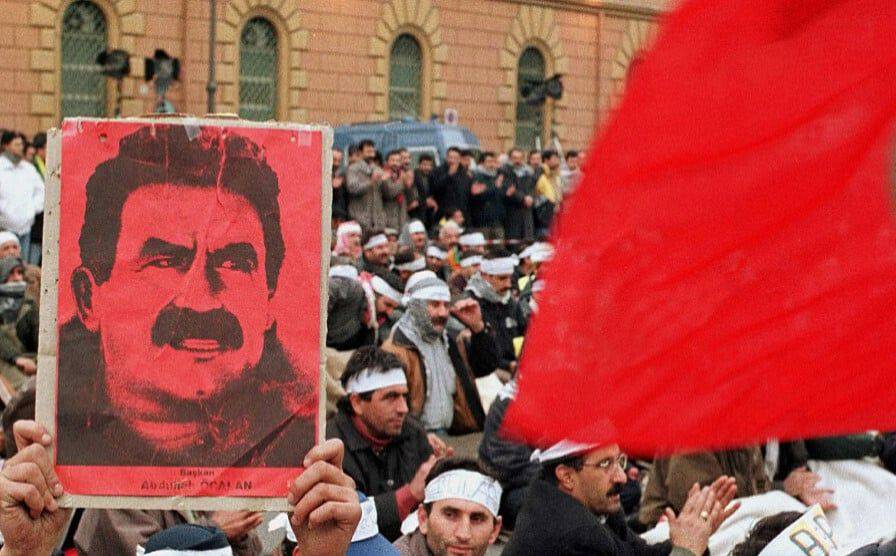

The authoritarian degeneration of Soviet-style socialism can be seen as a decisive historical experience that profoundly reshaped Abdullah Öcalan’s relationship with the socialist paradigm. From the late 1990s onward, Öcalan interpreted the collapse of the Soviet Union not merely as a victory of imperialism but also as the structural failure of state-centric socialism [6].

At the heart of this critique lies the rapid bureaucratization of the state built in the name of the proletariat, its suppression of popular will, and the reproduction of a centralized power that excluded women and local communities. Öcalan argued that this was not simply a historical deviation, but a form of domination encoded within Marx’s very concept of the transitional state [7]. Consequently, rather than adopting the Soviet model, he pursued a political system based on direct democracy, local self-governance, and the transcendence of the state.

This pursuit intersected with Murray Bookchin’s concepts of social ecology and libertarian municipalism, evolving into a stateless yet organized model of communal life known as democratic confederalism. In this way, Öcalan redefined the socialist promise of liberation through a vision of people’s sovereignty independent of the state and free from centralism.

At the center of Öcalan’s critique of actually existing socialism lies the sanctification of the state and the suppression of popular will through bureaucratic apparatuses. In his view, the Soviet Union and similar regimes, despite claiming to be alternatives to capitalism, reproduced the core structural codes of capitalist modernity—centralization, progressivism, and industrialism[8].

Viewing the state as a “transitional tool,” substituting the revolutionary subject with the party apparatus, and replacing the class with the vanguard cadre all rendered popular participation impossible. In this light, Öcalan saw real socialism not only as a historically failed model but also as a form of domination incompatible with libertarian principles. For him, the collapse of socialist systems resulted not primarily from external interventions, but from their internal dynamics of authoritarianism.

Another central criticism lies in the systematic neglect of gender and ecology. Öcalan argues that class-based analyses treated women's liberation and the relationship with nature as secondary issues, seriously limiting socialism's transformative capacity [9].

Yet a true struggle for freedom requires a multidimensional approach—one that fights not only against class exploitation, but also against patriarchy, ethnic assimilation, and domination over nature. Accordingly, Öcalan redefined socialism as a model based not on the state, centralism, or homogeneity, but on multiplicity, self-governance, and the principles of an ethical-political society. Shaped under the name of “democratic modernity,” this model represents an effort to build a third path in opposition to both the liberal and state-socialist forms of capitalist modernity [10]. (EJA/VK)

I - Will the revolution be with or without the state?

II - The construction of actually existing socialist practices

Notes

1 - Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Armed: Trotsky 1879–1921, Verso, 2003.

2 - Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, Oxford University Press, 1963.

3 - Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists, AK Press, 2005.

4 - Alexander Berkman, The Bolshevik Myth, Dover Publications, 1971.

5 - Mikhail Bakunin, Statism and Anarchy, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

6 - Abdullah Öcalan, Current Issues in Sociology, Aram Publications, 2007.

7 - Abdullah Öcalan, Manifesto of Democratic Civilization, Volume 1, Aram Publications, 2009.

8 - Janet Biehl, Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin, Oxford University Press, 2015.

9 - Dilar Dirik, The Kurdish Women’s Movement: History, Theory, Practice, Pluto Press, 2022.

10 - David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004.