"When I was a kid, I'd tell my mother that I wanted to become an artist. I don't think she took me seriously back then, because this didn't seem like a realistic career (it still doesn't). I loved drawing a lot as a kid, then as a teenager I realised that I could express my inner 'self' in words too. You can say that my life has been one long attempt at finding ways of combining images and words." This is how Raphael Vella, artist, editor and Art co-ordinator within the Faculty of Education at the University of Malta talks to Babelmed.net about his involvement with the arts.

You are an artist, curator and educator. How do you manage these three 'occupations'? Are they separate activities in your life or do they feed off each other?

The answer is that I'm not sure whether I manage to do all three activities as well as I'd want to. I don't see myself as a full-blown, freelance curator; actually, I'm more like an artist who is also interested in working with other people's ideas and works. Then, my role as a lecturer within a university exposes me to other areas of art: education, advocacy, emerging art, and so on. Whatever I do, I'm never far away from the actual process of making art, so art practice remains central to all or most of my activities. But I realised many years ago that Malta lacks the infrastructures that artists in other European countries take for granted, so Maltese artists simply cannot wait for these things to fall from the sky. For instance, I realised that nobody was writing seriously and theoretically about contemporary art, so I became deeply involved in art theory and criticism. And if nobody is interested in writing the history of Maltese contemporary art (or if it is being written only by those who do not really have the desire to understand it), then Maltese artists need to write their own history. From an academic perspective, this is a bit absurd, because you cannot write your own history and simultaneously keep a critical distance from the 'subject'. But if one keeps in mind the fact that I and some others like Mark Mangion (of Malta Contemporary Art) were so central to the creation of artists' groups, exhibitions by Maltese and non-Maltese artists, artists' publications, and so on, then I guess that one can also understand the importance of listening to the voices of those who were there when things happened.

You have been very active in promoting contemporary art in Malta. Which do you consider to have been your greatest achievements/successes? Why?

It is not a cliché to say that one couldn't have done anything without the help, and sometimes, the guidance, of others. It's very true. The challenge is to find the right individuals for the right task; believing in other people is also an 'achievement'. I like working with other people on my projects, though I admit it's far from easy at times. Coordinating the work of others, especially young people, usually gives me a lot of pleasure, hence my interest in education. The changes I made to the Art programme within my faculty transformed the outlook of our students, and I like to think that this is a small achievement too, but it wouldn't have been possible without the help of other lecturers.

Recently you curated 'Relocation' and very soon your Masters students will be having their end of course exhibition 'Strati' ... are they similar in any way? How does your curatorial role (involvement in the selection of works, organisation, etc) change? Do you differentiate between artists and students? In what way? Why?

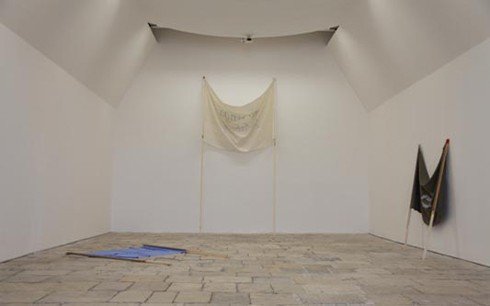

These exhibitions are in fact very different from each other. I never select students for exhibitions I'm curating, because I'd consider this to be ethically problematic. Once the students graduate and move on to develop their own work, then the situation changes. In fact, I do work with ex-students at times. And there is also a clear difference between Masters students and undergraduate students. While I encourage all students to develop their own ideas and research into exhibitions or installations, undergraduate students generally need more guidance because, in many cases, this would be their first experience of showing work to a public. It's not easy to show your work for the first time, though I can't say I remember that feeling with any clarity (too many exhibitions!). 'Strati' is a research exhibition of works and process documentation by a group of students in a Masters programme I coordinate at the University of Malta. There's no overarching theme in it. 'Relocation' was different. There, I was commissioned to conceive an idea for an exhibition and choose artists to sustain and possibly challenge that idea. I thought the problem of the relocating Maltese artist - moving both physically and intellectually between Malta and beyond was relevant and could be 'illustrated' with a diversity of works and media. Basically I had a thesis about contemporary Maltese art, and the challenge was to give this thesis a visual form by picking works that either dealt with this issue directly or else indirectly by avoiding it.

What are the challenges of art education in Malta? How prepared are Maltese art teachers and teachers in general to face the new challenges which contemporary society presents?

I think art education is challenged everywhere, not only in Malta. It's always difficult to convince people to invest money, time and space in something as unstable as human emotions, ideas, performance, and so on. In Malta, there have been some improvements in recent years, but the main issue remains one of a dearth of provisions. You can see this at primary level but also at tertiary level. I am positive, though, that many younger teachers are becoming more aware of how to present the subject to children in schools and are also exposing themselves more frequently to different ideas in educational institutions in other European countries.

How do you feel about Malta not having a National Museum of Modern and Contemporary art? How would it change your position/work?

My real concern is not whether a Museum of modern and contemporary art will ever materialise, but whether it will be done well whenever it materialises. The question of whether we need one or not is no longer even a question, to my mind. You cannot hope to form part of a larger world or political entity like the EU without showing a clear interest in the intellectual, artistic and technological development of the country. But if we end up with an embarrassing museum, then I think I'd rather have nothing at all. We all know that as long as you have nothing, you can at least hope that something good will happen, but when a new institution is made badly, the country is stuck with it for years, with no hope of improvement.

You are constantly in touch with young people, aspiring artists (to use a cliché). What do you feel/think about this new generation of creators? How do they differ from previous generations?

There are many differences: more international outlook, more prone to travel, more regular shows outside the country, more technologically oriented, less didactic, less existentialist. Actually, I think that the main difference is that young artists are becoming less self-conscious about their 'Malteseness', less prone to allow the cultural insularity and local restrictions to affect their work in a direct way. I wrote once that we will only become artistically 'independent' (if that is at all possible or desirable) when we stop thinking about becoming independent. This problem of the 'centre' and the 'margins', and how this problem has affected my generation and younger artists, is an issue that has interested me for some years now. Being born outside a perceived 'centre' is clearly something that can only be understood if you experience it yourself. I recently showed a short text I wrote about contemporaneity and marginality to a young artist from Vienna, and she realised after reading it that Austrian artists - unlike Maltese artists - feel that they are at the centre of things, despite coming from a relatively small country. I think that education combined with more hybrid artistic methodologies today are helping younger Maltese artists to move away from this marginality.(ÇT)