Israel’s settler colonial regime seeks to keep under its direct control not only people, borders, and resources across the Palestinian territories, but also communication, information, and digital infrastructure. In our previous article, “From Productive Force to Destructive Force: Digital Colonialism in Palestine” we examined how this digital colonialist structure functions on three interrelated levels: the Israeli control over telecommunications infrastructure, the systematic use of surveillance technologies against Palestinians, and the restriction of online spaces of expression.

The article you are about to read focuses on the diverse forms of resistance developed against this regime of digital colonialism. Of course, as long as the settler colonialism and apartheid structures persist, the impact of these practices remains limited. Yet every crack opened in the walls of settler colonialism continues to widen the ground of struggle.

1) Alternative Access Efforts under the Digital Blockade

One of the most challenging fronts in the struggle against digital colonialism lies in the realm of hardware and communication infrastructure. Israel keeps telecommunications and internet networks across the Palestinian territories under tight control. Although the Oslo Accords in the 1990s partially transferred certain powers to the Palestinian Authority, Israel never gave up control over the critical components of the infrastructure. This situation has prevented the development of an independent digital network in Palestine, while enabling Israel to sustain mass surveillance practices and to restrict Palestinians’ digital rights. This domination over infrastructure operates in different ways across various parts of the Palestinian territories.

Gaza: Disruption, resistance, and alternative connections

In Gaza, Israel controls the communications infrastructure by both technical and political means; this same infrastructure also becomes a direct target of its attacks. With the escalation of assaults since October 2023, these interventions have intensified further: power plants, base stations, fiber lines, and media centers were systematically destroyed. Journalists have been among the deliberate targets of these attacks. According to an analysis by Access Now published in November 2023, internet connectivity in Gaza had dropped by more than 80 percent; and by August 2024, as reported by the Associated Press, at least 70 percent of the territory’s telecommunications infrastructure had been destroyed.[2][3]

Despite this devastation, Gazans have long developed new methods to overcome the blockade on communication. Even under the extreme conditions following October 2023, this resistance did not cease: eSIM donation campaigns, portable hotspot devices, radio systems, and mobile signals intercepted from neighboring countries have all been mobilized to restore connection.

eSIM Solidarity against Internet Blackouts

Immediately after the massive communication blackout in October 2023, an international campaign emerged to reconnect Gaza with the outside world. From Egypt to Lebanon, from Europe to the United States, volunteers mobilized to provide people in Gaza with internet access through eSIM technology. Palestinians in the diaspora and supporters worldwide purchased eSIM packages from their local operators and sent the QR codes to Gaza. One of the most visible examples of this solidarity was the #ConnectingGaza campaign launched by Cairo-based journalist Mirna El Helbawi. On October 28, El Helbawi made a call on X (Twitter), inviting individuals to purchase eSIM packages and share the corresponding QR codes with people in Gaza.

The campaign quickly turned into a global movement of solidarity. According to El Helbawi’s statements, by mid-December 2023 donations from 94 different countries had reached a total value of 1.25 million dollars, enabling more than 50,000 Gazans to reconnect to the internet. Donors purchased eSIM packages from their own mobile operators and sent the QR codes to El Helbawi via email or message. El Helbawi and her volunteer team then forwarded these codes to those in Gaza who still had limited internet access, and these recipients in turn used the codes to provide connectivity to phones around them.

Mirna El Helbawi’s call for eSIM support on X:

الغذاء والدواء والتواصل هم حقوق أساسية من حقوق الإنسان. نحن كفريق عمل الحملة فخورين كوننا جزء من دعم غزة بتمكين مئات الآلاف من سكان قطاع غزة؛ شماله ووسطه وجنوبه، من التواصل مع بعضهم البعض ومع المستشفيات ومع الإعلام ومع العالم الخارجي.

— Mirna El Helbawi (@Mirna_elhelbawi) November 24, 2023

قطع الإتصالات والإنترنت هو سلاح قوي وفعّال… pic.twitter.com/nCCRnATlGS

In addition to #ConnectingGaza, other initiatives also emerged. The Jordan-based volunteer group Gaza Online matched donated eSIMs directly with families in need and provided technical support via WhatsApp. The #ReconnectGaza campaign, involving organizations such as the digital rights group 7amleh, continued to advocate not only for eSIM donations but also for the delivery of satellite internet, emergency communication stations, and mobile connectivity solutions to Gaza through international pressure.

“Network trees”: Local access points

One of the most innovative efforts to restore internet connectivity in Gaza came from the Italy-based Associazione di Cooperazione e Solidarietà (ACS), which launched the GazaWeb project and developed what are called “network trees.”

The operating principle of this system is simple yet effective: signals from Israeli or Egyptian base stations still within range in border areas are captured by smartphones equipped with eSIMs. These phones are placed inside waterproof boxes with power banks on rooftops or tall poles where the signal is strongest, and share wireless internet (Wi-Fi) with nearby users through their hotspot feature. These setups are colloquially referred to as “trees,” while the volunteers who install and maintain them are called “gardeners.”

Since early 2024, the GazaWeb team has managed to establish at least 15 access points in areas such as Gaza City, Rafah, Deir al-Balah, and Jabalia. However, building these points entails serious security risks. When too many people try to connect in one location, Israeli forces often interpret the crowd as “suspicious activity” and use it as a pretext for attack. On June 26, 2024, a bomb was dropped on civilians gathered near one such network tree in the Jabalia refugee camp, killing at least eight people. In an interview with Euronews, ACS project coordinator Manolo Luppichini stated that this was the third such incident and that more than twenty people had been killed while trying to re-establish internet connectivity in Gaza. [7]

Despite these attacks, GazaWeb volunteers remain determined to continue their work. Recently, in order to prevent people from becoming targets in open areas, the “tree” systems have been moved indoors. To allow women and children to access the internet without going outside, phones are hung from balconies or windows, enabling signals with a range of two to three kilometers to reach indoor spaces.

West Bank: Alternative communication under restricted access

While the internet infrastructure in the West Bank has not been physically destroyed to the same extent as in Gaza, digital mobility is heavily constrained. Israel keeps direct control over all critical components of the telecommunications network — including frequency allocation, backbone access, and device licensing. This structural dependency not only prevents Palestinian operators from developing their own networks but also forces users to find alternative means to circumvent censorship and remain connected.

One of the most common methods is the use of SIM cards belonging to Israeli operators. These cards, which offer far better coverage and connection speeds, are used by hundreds of thousands of people in the West Bank. According to Reuters, between 2016 and 2018, between 370,000 and 500,000 Israeli SIM cards were in use in the region. [8] This creates a paradoxical situation both economically and politically: to overcome the restrictions imposed by colonial control, Palestinians are compelled to rely on products from the very network of domination.

Similarly, residents in border areas benefit from the signal spillage of Jordanian networks to establish alternative connections. Especially around Jericho and the Jordan Valley, signals from Jordanian mobile operators occasionally extend into the West Bank, allowing people in these areas to connect using Jordanian SIM cards. [9]

Even though internet access remains systematically restricted, alternative communication channels such as FM and internet radio are widely used by Palestinians. For example, the Ajyal Radio Network broadcasts across 22 frequencies in different parts of the West Bank: 103.4 MHz in Ramallah, 92.8 MHz in Jenin, and 100.4 MHz in Jericho and the Jordan Valley. This distribution allows communities isolated by geographical and political barriers to communicate through radio. Another important example is Radio Nisaa, a station that aims to amplify women’s voices.

Through its network of female reporters, Nisaa sustains the flow of news and amplifies women’s perspectives in the struggle for gender equality. [10]

Radio broadcasters operate not only on traditional FM/AM bands but also through internet-based platforms. Founded in Bethlehem in March 2020, Radio Al-Hara has become known as an online station that gives space to “marginalized” voices. During the COVID-19 lockdown, it organized 72-hour live sessions under the title “Sonic Liberation Front,” linking up with international solidarity networks. [11][12] Such internet radios enable the continuity of communication by operating over low-bandwidth connections in regions where the available bandwidth is extremely limited.

Radio and online broadcasting have thus emerged as flexible communication practices developed to sustain the circulation of information under colonial control that deliberately weakens digital infrastructure. In moments when connectivity is cut off and mobile networks are unusable due to surveillance or frequency restrictions, radio remains the most reliable means of transmission.

2) Defying surveillance systems

In occupied Palestine, surveillance functions as a form of control that permeates every aspect of daily life. People know they are constantly being recorded; as a result, they have become reluctant to socialize in public or to protest under the watch of cameras. [13] Reports by digital rights organizations show that East Jerusalem, Hebron, and Nablus today have some of the most densely monitored camera networks in the world. [14]

Palestinians are developing both technical and creative methods to subvert this pervasive surveillance. Among the most common practices are using masks, keffiyehs, and reflective glasses to mislead facial recognition systems, and temporarily covering camera lenses or blind spots with spray paint or laser pointers.

Another strategy lies in the widespread use of digital privacy tools. As surveillance risks have intensified, many Palestinians have moved away from Meta-owned applications and turned to alternative messaging platforms that provide end-to-end encryption. Field observations show that particularly younger users have made tools such as the Tor browser, VPNs, and other anonymity-based applications part of their daily routines. Numerous reports indicate that digital rights defenders across the West Bank now treat these tools as “everyday survival practices.”

Surveillance, however, is not limited to data traffic. In 2021, spyware developed by the Israeli company NSO Group, known as Pegasus, was discovered on the phones of numerous individuals, including human rights workers [15]. These cases revealed that Palestinian civil society had been directly targeted, exposing the depth of Israel’s digital occupation.

On the ground, the Israeli military also deploys facial-recognition applications called Blue Wolf and Red Wolf, which collect photos of Palestinians and build an enormous biometric database across occupied cities. With these applications, soldiers can scan a person’s identity within seconds at checkpoints. The software classifies individuals with “red,” “yellow,” or “green” codes, determining who is allowed to pass and who must be detained. In response, Palestinians have developed counter-mapping practices to reverse these systems of control. Telegram channels share the locations of Israeli patrols, mark checkpoints, and guide drivers to alternative routes. [16] Around Hebron and Nablus, “camera detection” groups photograph newly installed surveillance cameras and report them to civil society organizations; this information is then compiled into open-source maps used by local communities.

At the international level, efforts to hold surveillance companies accountable are also growing. Firms such as Hikvision (China) and TKH Security (Netherlands) provide hardware and software infrastructure for facial-recognition-based surveillance networks in East Jerusalem and Hebron. [17] These companies, linked to Israeli partners, attempt to protect their reputations by adopting marketing terms like “human-rights-conscious surveillance technology” or by rebranding. Yet digital rights groups describe these tactics as “technological whitewashing” [18]

3) Constructing the narrative of a free Palestine

The struggle to build the narrative of a free Palestine represents one of the most significant forms of resistance against digital colonialism. As discussed in the previous sections, despite the systematic destruction of communication infrastructure and the encirclement of daily life by surveillance technologies, Palestinians continue to create their own networks, their own language, and their own regimes of truth. At the core of this effort lies not only the will to “stay connected,” but the determination to define who speaks, what is told, and how it is told. From Gaza to Ramallah, from diaspora collectives to international solidarity networks, this ongoing effort seeks to produce its own counter-narrative amid censorship and algorithmic silence.

Struggling on social media

For years, Palestine’s digital presence has been systematically suppressed. Platforms such as Meta, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and YouTube frequently flag and remove Palestinian users’ content as “violent” or “terrorism-related,” reduce its visibility, or suspend entire accounts. 7amleh’s 2024 report, “Erased and Suppressed: Palestinian Testimonies of Meta’s Censorship” documents numerous incidents after 2023 in which content related to Gaza was deleted or accounts were suspended. Similarly, Sada Social’s digital monitoring reports show that social media companies not only delete content but also employ algorithmic tools to make pro-Palestinian accounts invisible — a practice known as shadow banning.

Under such conditions, Palestinian users have developed both technical and cultural strategies to remain visible on social media. Following growing reports that platforms disproportionately remove Palestine-related content, users began employing creative forms of “algospeak” to bypass algorithmic censorship. [19] These include deliberately mixing Arabic and English, omitting punctuation marks, or distorting key words (for example, writing “Gzz” instead of “Gaza,” or “Plestn” instead of “Palestine”). An article published in Big Data & Society describes such linguistic tactics as “algorithmic resistance” — a counter-writing practice against the linguistic colonization embedded in digital systems.[20] These distorted spellings function not only as tools to evade filters, but also as acts of digital existence for a people whose identity is being systematically erased.[21]

Beyond tactical resistance, institutional counter-censorship mechanisms are also being built. The “7or” Digital Rights Observatory, developed by 7amleh, systematically documents incidents of censorship experienced by users. Each reported case becomes both statistical evidence and a resource for legal advocacy — linking individual experiences into a collective database. Similarly, Sada Social communicates directly with social media companies to have wrongfully removed accounts reinstated.

Organizations such as 7amleh, Access Now, and SMEX jointly issue statements against the censorship and surveillance policies of tech corporations, holding companies like Meta, Google, and Amazon accountable for transparency and fairness. For example, following growing public pressure, Meta was forced at the end of 2023 to acknowledge that certain Palestine-related posts had been mistakenly removed and promised to make its policies “more equitable and transparent." [22]

Journalists and citizens on the ground have also become key actors in this digital narrative. The independent news account Eye on Palestine has been publishing content from the field via Instagram and X since 2014; with millions of followers, it has been repeatedly suspended, becoming a direct target of censorship. The Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU) verifies footage from Palestinian journalists and shares it with international media through English-language infographics. Meanwhile, the Palestinian fact-checking initiative Kashif operates as an Arabic-language verification platform through WhatsApp and Facebook, creating an internal fact-checking network to counter misinformation.

Another form of social media resistance emerged in 2021, during the forced evictions in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. In protest against Facebook and Instagram’s censorship, Palestinian users launched a mass campaign: tens of thousands of people rated these apps with one star on the App Store and Google Play, drastically lowering their scores. This collective digital action made the issue of online censorship against Palestinians visible on a global scale.[23]

All these examples show that social media has become not only a space of propaganda but also a front in the struggle for data justice. Palestinian digital rights organizations emphasize the notion of “digital justice,” linking the demand for freedom of expression with calls for technical transparency and corporate accountability.

Evidence-based counter-narratives: Exposure, verification, and forensic visualization

The Palestinians’ struggle to reclaim their own narrative is not only about gaining visibility, but also about confronting the question of how truth is proven. What Israel attempts to conceal through high-tech means is being documented and exposed through investigative journalism and digital forensic analysis.

One of the most important examples of this approach is the investigative work of journalist Yuval Abraham, published in +972 Magazine — research that we have both drawn on extensively and partially translated into Turkish. Abraham revealed the existence of Israel’s AI-driven systems “Lavender” and “Habsora,” which automate lethal targeting decisions within the Israeli army’s operations. His investigations into the digital infrastructure of Israel’s war on Palestine go beyond these two systems, exposing the deeper entanglement between Israel’s technology strategy and major global corporations. He has shown, for instance, that Microsoft provides cloud services to Israel’s intelligence unit Unit 8200, enabling large-scale analysis of data collected from Palestinians, and that Amazon has developed joint projects with the Israeli Ministry of Defense, becoming part of the digital surveillance apparatus over Palestinian society.

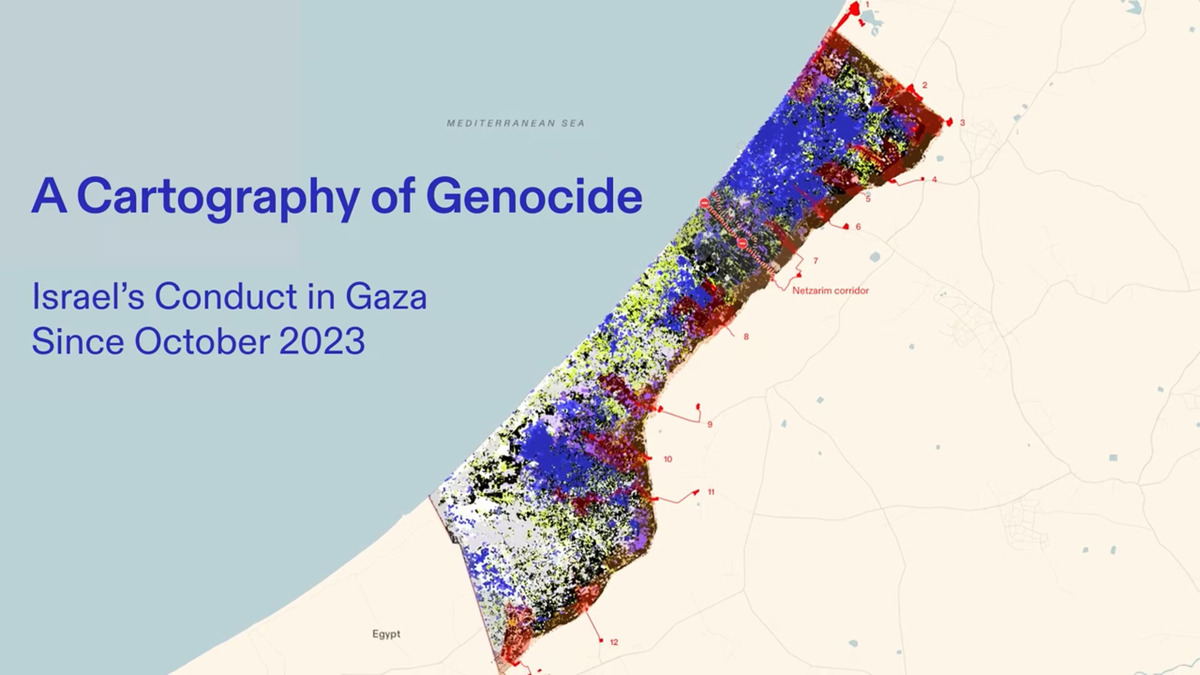

One of the most prominent collectives strengthening the forensic–spatial dimension of this work is Forensic Architecture (FA). Based at Goldsmiths, University of London, FA brings together methods such as satellite imagery, open-source video analysis, 3D modeling, acoustic investigation, and space-time reconstruction to forensically examine attacks in Gaza and many other cases.

FA’s 2024 report “Humanitarian Violence in Gaza” demonstrates that the Israeli army’s rhetoric of “safe zones” and “evacuation corridors” functions as a mechanism for civilian displacement. Satellite images clearly show that populations forced from north to south were later bombed in those same “safe” areas. Another study, “Destruction of Medical Infrastructure in Gaza,” documents the systematic targeting of 28 hospitals, proving that these were not “collateral damages” but part of a planned strategy to collapse the healthcare system. In “No Traces of Life: Israel’s Ecocide in Gaza (2023-2024),” FA evidences the deliberate targeting of farmland, greenhouses, and fishing harbors — linking ecological destruction to the broader annihilation of Palestinian life.

An FA investigation conducted as a continuation of these studies examined the visual materials presented at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) during South Africa’s genocide case against Israel in January 2024. The Israeli defense team had submitted maps, photographs, and videos intended to legitimize its attacks on Gaza, claiming that “Hamas was using civilian areas for military purposes.” However, FA’s analysis revealed that many of these visuals had been manipulated: several locations described as “rocket launch sites” were, in fact, bomb craters, while areas presented as “zones of militant activity” were identified as civilian structures such as schools and hospitals.

As FA researcher Júlia Nueno explains, the collective’s practice “questions how states construct truth.” Their work reminds us that evidence cannot be separated from power relations; architectural knowledge here becomes not only a technical tool but also an instrument of justice and political testimony. FA’s investigations therefore do more than make crimes visible — they actively participate in the public reconstruction of truth.

On the auditory front, this approach is carried forward by the Earshot collective, an independent London-based group working in the lineage of Forensic Architecture. Earshot focuses on the forensic capacity of sound, analyzing audio recordings, videos, and witness testimonies to document human-rights violations in Gaza and the West Bank. In its investigations “5 Attacks on Journalists in Palestine” and “The Killing of Layan Hamada and Hind Rajab” the group examined the sounds of gunfire and explosions to identify Israeli army attack patterns.

Earshot’s analysis of the killing of Ameen Sameer Khalifa at the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation site:

Another project by the collective, “22 February 2023 Raid on Nablus” synchronizes environmental sounds — such as gunfire, screams, and vehicle movements — recorded during an operation in the West Bank with location and time data. In doing so, they create acoustic maps of testimony, even in situations where no visual material is available.

Earshot’s approach expands the boundaries of forensic visualization: evidence becomes not only something seen, but also something heard. In this way, testimony gains a sensory dimension as well as a spatial one.

Visualizing the Palestinian narrative

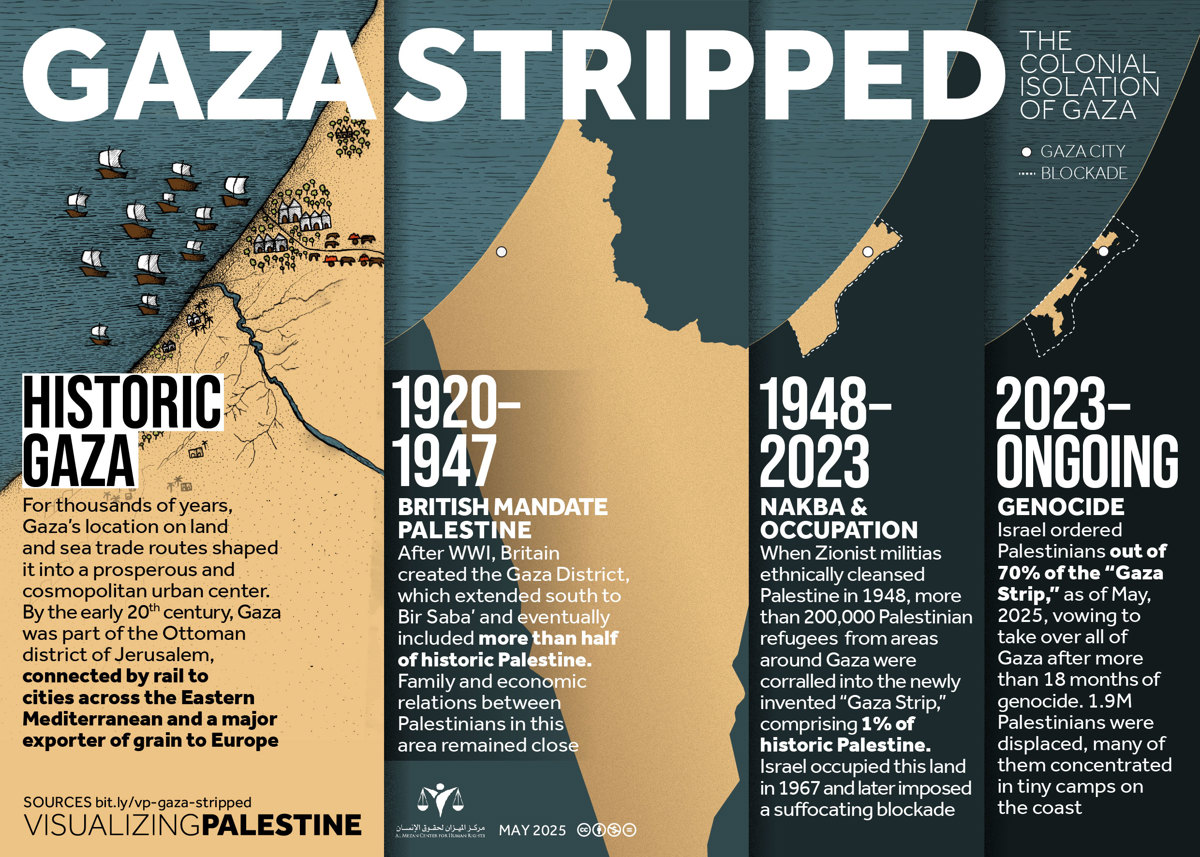

Visuality has become increasingly central to the Palestinian narrative. Maps, infographics, digital archives, and games simplify the complex structure of occupation, transforming data into tools of documentation and political communication. One of the best-known representatives of this approach is the collective Visualizing Palestine (VP), founded in 2012. Guided by the principle of “visualizing justice through data” VP makes human rights violations visible through statistics, maps, and narrative graphics.

Among VP’s prominent projects, “Who’s Complicit?” illustrates—through network maps—the multinational corporations indirectly supporting Israel’s settlement policies. By mapping the relationships between corporations, subcontractors, and research institutions, it exposes the global dimension of the occupation economy. Another project, “Stop Killer Robots,” analyzes Israel’s AI-based targeting systems, using data-driven graphics to show how these technologies contribute to civilian deaths. VP’s approach treats data not merely as a source of information, but as a political ground for storytelling. Issues such as child detention, home demolitions, and the theft of water resources are visualized through graphics that merge numerical data with personal stories—conveying not abstract numbers but the lived, spatial and human context of Palestinian experience.

Visualizing Palestine also produces multilingual materials—Arabic, English, French, and Spanish versions—to reach diverse communities. The datasets and sources used in each visual are publicly shared, allowing researchers, journalists, and activists to reuse them in their own work. By employing visuality as both evidence and narrative form, VP contributes to the global circulation of the Palestinian story.

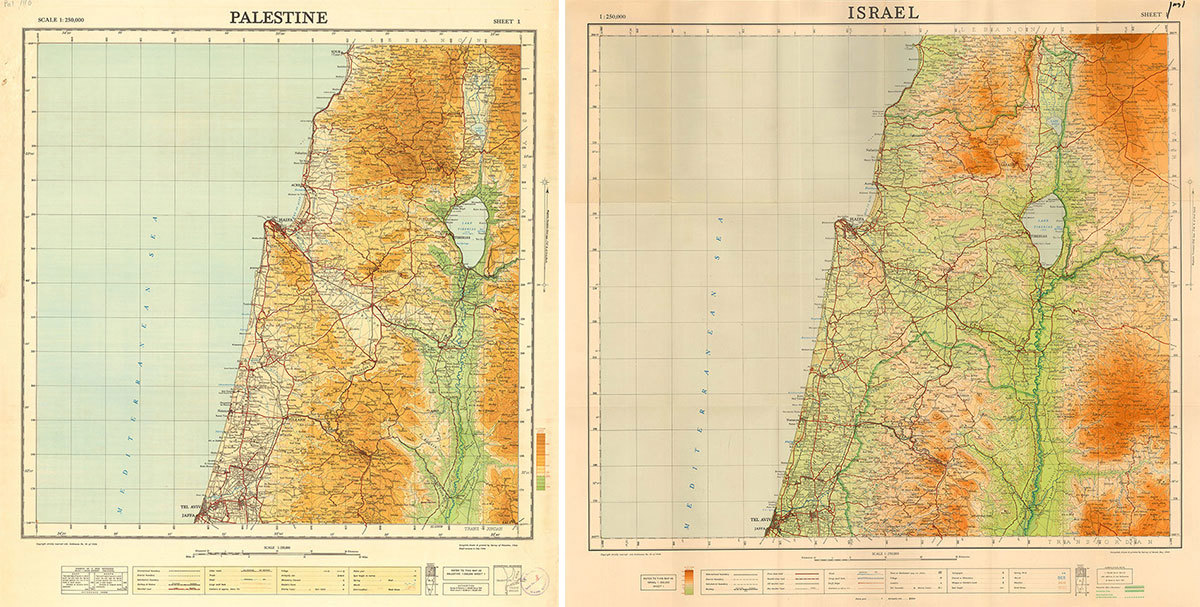

As an extension of this visual-political line, digital mapping and archiving projects have emerged as counter-memory practices against colonial spatial erasure. Israel rewrites geography by deleting the names of hundreds of Palestinian villages on platforms such as Google Maps and Apple Maps, or by restricting access to high-resolution imagery of certain regions.

One of the most significant efforts to resist this is the Palestine Open Maps (POM) project. POM digitizes hundreds of maps from the British Mandate period (1920–1948) and makes them publicly accessible. The platform overlays pre-1948 villages, roads, and place names onto today’s satellite imagery, allowing users to see the locations and spatial memories of destroyed villages. During “mapathon” events held in Ramallah and Beirut, volunteers annotate the maps with lost village names and oral testimonies, turning the archive into a living atlas of collective memory.

A similar initiative is the Palestinian Oral History Archive (POHA), run at the American University of Beirut. Created in partnership with the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs (IFI), the Nakba Archive, and the Arab Resource Center for Popular Arts (AL-JANA), this digital collection makes publicly available over 1,000 oral history recordings of those who witnessed the 1948 Nakba. POHA turns experiences of displacement and exile into a public practice of remembrance, not just an academic resource.

One of the most original forms of counter-narrative against digital colonialism has also emerged in video games. Palestinian game designer Rasheed Abueideh’s 2016 mobile game Liyla and the Shadows of War tells the story of a father trying to save his young daughter during the 2014 Gaza War. Initially rejected by Apple’s App Store for containing “political content,” the game became a symbolic example of the censorship Palestinians face in the digital realm. Liyla soon reached millions of players worldwide, proving that even the space of gaming can become political. Abueideh’s new project, Dreams on a Pillow, centers on the 1948 Nakba and aims to reconstruct the emotional topography of exile through real testimonies and family archives.[25]

This creative field is not limited to individual efforts. The platform Palestinian Voices in Games, founded in 2024, seeks to make Palestinian game developers visible within the global industry and to facilitate resource sharing. By connecting designers and their projects, it functions both as a network challenging the colonial representations of the Western game industry and as a space for collective digital production. Among the platform’s featured works is Pomegranates, an experimental game by Palestinian designer Yasmine Batniji, set in Gaza and focused on reconnecting fragmented memories through objects and spaces. By inviting players to “return to the map” and rebuild ties between past and future, the game transforms artistic creation into a form of resistance.

4) Organizing the struggle across borders

Israel’s occupation and aggression policies are sustained not only by state power but also through the active support of U.S.-based global technology corporations. Cloud infrastructures, artificial intelligence systems, and big data services have become integral components of policies of displacement and annihilation against Palestinians. Thus, digital colonialism extends far beyond a technical or economic issue — it has taken root as a global regime of domination legitimized through corporate and geopolitical alliances. As highlighted by UN Special Rapporteur on Palestine Francesca Albanese, the oppression that spans from digital infrastructure control to surveillance technologies and media narratives is carried out through the coordinated power of transnational companies and allied states. [26] For this reason, the struggle against digital colonialism cannot be confined to a single front; it requires simultaneous forms of solidarity developing across different scales and sectors.

Resistance to digital colonialism is not merely a demand for freedom of expression; it is also a struggle to re-establish collective control over the productive forces. The key steps of this struggle involve politicizing spectrum, infrastructure, and data for the public good; strengthening democratic oversight against platform monopolies; and organizing the institutional disengagement of academia, trade unions, and technology workers from colonial projects through boycott, exposure, and contract termination. The growth of the Palestinian resistance on the digital front therefore depends on linking local struggles with international campaigns and building transnational organizations against imperialism.

Boycott as a method of struggle: The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) Movement

One of the most influential transnational initiatives of the Palestinian struggle is the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, founded in 2005. Inspired by the anti-apartheid boycotts in South Africa, BDS seeks to end global public support for Israel’s occupation, oppression, and apartheid policies, and to pressure Israel to comply with international law. The movement encompasses a wide repertoire of actions — from consumer boycotts and corporate divestments to the rejection of academic and cultural collaborations, as well as calls for governmental sanctions. In doing so, it provides a global platform for the Palestinian people’s struggle for freedom, justice, and equality, while aiming to achieve Israel’s economic and political isolation.

As Israel’s digital colonialism expands on a global scale, the BDS movement has increasingly turned its focus toward the technology sector. According to the BDS National Committee, after the arms industry, technology companies rank among the largest enablers of Israel’s occupation regime and its crimes in Gaza. For this reason, the movement conducts boycott campaigns against companies that provide services to the Israeli military in the field of information and communication technologies. Hewlett Packard (HP) has long been one of the main targets due to its role in supporting Israel’s biometric identification systems and occupation infrastructure. Similarly, Microsoft has faced criticism for its partnerships in cloud computing and artificial intelligence projects. After it was revealed that Microsoft technologies were being used in surveillance operations targeting Palestinians, Palestinian groups and their supporters began to boycott Microsoft products. The BDS movement officially added the company to its boycott list and launched campaigns under the hashtag #BoycottXbox, urging consumers to boycott products such as the Xbox gaming console.

.@Microsoft is a new BDS priority target. Here's why you should boycott @Xbox and pressure your institutions to exclude Microsoft from its contracts. #BoycottXbox pic.twitter.com/I0ee3xikEs

— BDS movement (@BDSmovement) April 9, 2025

Another key example that the movement has focused on is the Project Nimbus agreement between Amazon and Google and the Israeli government — a multibillion-dollar contract granting the Israeli military access to the companies’ cloud computing infrastructure. BDS, together with initiatives such as No Tech for Apartheid, organized global protests demanding the cancellation of the contract. Through these efforts, the boycott front expanded beyond the Israeli state itself, targeting the global technology corporations that sustain its mechanisms of oppression and transforming the boycott into a strategic struggle against the technological supply chain. [27] As part of these campaigns, the involvement of companies such as Dell, Cisco, IBM, and Oracle in providing support to the Israeli military was also exposed. These corporations have since faced shareholder pressure, contract cancellations, and public boycotts as a result.

One of BDS’s most significant achievements has been demonstrating its ability to damage the reputations of global corporations complicit in Israel’s crimes in Palestine. As the movement’s advocates emphasize, “In the capitalist world, corporations care only about profit and image; the way to influence them is to show that supporting racist and colonial regimes carries an economic cost.” Through this strategy, BDS raises the cost of unconditional support for Israel across the global economy and media sphere, while building a universal framework of accountability against digital colonialism.

Tech workers rise up: A front of solidarity with Palestine

Alongside global boycott campaigns, the organized efforts of technology workers have opened a new front of struggle for Palestine. In particular, the deep collaborations between Silicon Valley–based tech giants and Israel are now being questioned from within these very companies by their own employees.

News of the Project Nimbus agreement, signed in 2021, surfaced around the same time as Israel’s bombardment of Gaza in May that year. The project revealed that Google and Amazon would provide the Israeli military with a multi-billion-dollar cloud computing infrastructure, sparking intense backlash within both companies. In October 2021, an anonymous open letter published in The Guardian by signatories describing themselves as “Google and Amazon employees of conscience” stated: “We believe that the technology we build should serve and uplift people everywhere, including all of our users. As workers who keep these companies running, we are morally obligated to speak out against violations of these core values.” [28] Bu mektubun ardından, ABD ve diğer ülkelerdeki 40’tan fazla sivil toplum örgütünün desteğiyle No Tech for Apartheid (NT4A) kampanyası kuruldu. Google ve Amazon çalışanlarının öncülük ettiği bu taban inisiyatifi, kısa sürede Microsoft, Apple ve Meta gibi şirketlerden de destekçiler kazanarak büyüdü. Kampanyanın hedefi, teknoloji ürün ve hizmetlerinin İsrail’in yerleşimci sömürgeci ve apartheid politikalarına alet edilmesini engellemekti.

It noted that, due to fear of retaliation, the authors remained anonymous, and that more than 90 Google employees and 300 Amazon employees had signed it internally. Following the publication of the letter, the No Tech for Apartheid (NT4A) campaign was founded with the support of over 40 civil society organizations across the United States and other countries. Led by Google and Amazon employees, this grassroots initiative quickly grew, gaining supporters from Microsoft, Apple, and Meta as well. The campaign’s goal was to prevent technology products and services from being used to advance Israel’s settler-colonial and apartheid policies.

The actions organized by No Tech for Apartheid (NT4A) revealed a new form of solidarity that goes beyond traditional union structures in the United States. On April 16, 2024, Google employees held a ten-hour sit-in to protest the Project Nimbus contract, with demonstrations taking place simultaneously at the company’s offices in New York, Sunnyvale, and Seattle. These protests became the largest workplace action ever organized against Google’s $1.2 billion contract with Israel. Following the demonstrations, nine Google employees — later dubbed the “Nimbus Nine” — were arrested by police at the company’s request. In a public statement, NT4A reported that Google’s management had directly coordinated the arrests, identifying the protesters through the company’s security cameras and employee ID logs.[29]

Shortly after the protests, Google management summarily fired 28 employees, including several who had not even participated in the sit-ins. The company justified its decision on the grounds of “policy violations,” yet NT4A and union representatives denounced the firings as a blatant act of retaliation and intimidation. In their official statement, NT4A wrote: “This flagrant act of retaliation is a clear indication that Google values its $1.2 billion contract with the genocidal Israeli government and military more than its own workers.” The statement continued: “In the three years that we have been organizing against Project Nimbus, we have yet to hear from a single executive about our concerns. Google workers have the right to peacefully protest about terms and conditions of our labor. These firings were clearly retaliatory.” [30] The declaration also named CEO Sundar Pichai and Google Cloud CEO Thomas Kurian, accusing them of profiting from genocide. As reported by The Guardian on April 27, 2024, the firings were part of a broader, systematic campaign of retaliation by Google against employees who had publicly criticized its involvement in Project Nimbus. [31]

Despite Google’s pressure, No Tech for Apartheid (NT4A) continued to organize protests in front of Google and Amazon offices, raised the issue of human rights violations in shareholder meetings, and carried out advocacy efforts in the U.S. Congress to highlight that Project Nimbus is incompatible with basic human rights principles.

In September 2025, it was revealed that Microsoft, through one of its cloud projects, had been storing surveillance data from Unit 8200, the Israeli army’s cyber intelligence division. Following this disclosure, a boycott campaign launched by NT4A and allied groups forced Microsoft to back down. This development was recorded as a tangible victory of global solidarity among technology workers and their supporters.

Another initiative challenging Big Tech’s complicity in Israel’s crimes is Apples Against Apartheid, a movement formed by Apple employees and digital justice advocates. The campaign emerged in late 2023, as Israel’s attacks on Gaza continued, to protest Apple’s silence in the face of these atrocities. In early 2024, hundreds of Apple employees signed and published an open letter titled “Apples4Ceasefire.” Addressed to CEO Tim Cook, the letter emphasized that “silence is complicity” and urged the company to support calls for a ceasefire. Later, in September 2024, during the week of Apple’s new iPhone launch, the campaign organized a global day of action called “Apple Accountability Day.” Protests were held in front of Apple Stores in more than ten countries — including New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, Berlin, and Sydney — where activists distributed flyers informing customers about Apple’s indirect complicity in the Israeli occupation. Campaign spokesperson Tariq Rauf highlighted that Apple had become “part of this debate” by opening offices in Israel: “By opening doors in Israel in 2012, Apple has immediately stepped right into the middle of the Palestine/Israel conversation, and try as they might, simply put they cannot avoid this subject forever.” Rauf added that public pressure on the company would continue to increase until Apple broke its silence. Apples Against Apartheid states that its goal is to dismantle the culture of fear and retaliation inside Apple and to encourage more employees to speak openly against the company’s stance on Palestine.[32]

One of the most prominent initiatives led by technology workers is Tech For Palestine, a movement founded in December 2023 by a group of software developers, engineers, and tech professionals. The initiative aims to harness technology in solidarity with the Palestinian people’s struggle for freedom. According to co-founder Paul Biggar, the idea for the movement began when his blog post titled “I Can’t Sleep,” written during Israel’s attacks on Gaza, went viral. In the aftermath, developers from around the world began reaching out to him, saying, “We want to work on projects that can help the Palestinian movement”. [33] Within a short time, more than 40 technologists came together, and once the call was made public, thousands of volunteers joined the Tech For Palestine network. Today, the movement functions as an open platform that brings together participants from different countries to develop digital tools and infrastructures supporting the Palestinian cause. Among the projects spearheaded by Tech For Palestine are Boycat, an application that helps users identify products connected to Israeli companies, and BuycatVPN, a secure connection tool developed by the same team. In addition, recent projects created by developers within the network include UpScrolled, an alternative social media platform, and JayWalk, an interactive mapping application designed for protest safety. These projects seek both to strengthen Palestinian solidarity networks in the digital realm and to build a new model of collective solidarity grounded in the ethical and political responsibility of technology workers.

5) Palestine’s Resistance to Digital Colonialism: A Call for Collective Struggle

Israel’s control over digital technologies targets not only Palestinians’ channels of communication but also their very modes of existence. From access to information to the right to visibility, from the ownership of networks to the governance of data, every domain is encircled by the digital extensions of settler colonialism. Cloud services, facial recognition systems, content censorship, and surveillance networks have turned communication from a fundamental right into a mechanism of control.

Under this siege, the rise of eSIM solidarity networks, VPN infrastructures, local access points, radio broadcasting, linguistic strategies to bypass algorithmic censorship, open archives, and forensic analyses represents far more than technical solutions. Through these tools, Palestinians preserve collective memory, articulate their own narratives, and reconstruct the public sphere. These digital practices are not only contemporary responses to dispossession but also the continuation of a long tradition of resistance.

This line of resistance grows stronger as it transcends the local. Initiatives such as BDS, No Tech for Apartheid, and Tech for Palestine make the global architecture of digital colonialism visible, shifting the debate from products to supply chains, contracts, and institutional mechanisms. By exposing Big Tech’s complicity in the occupation regime, these movements link the demand to “socialize technology” with concrete calls for contract termination, transparency, independent oversight, and workers’ right to collective voice.

When digital counter-practices intersect with political struggles on the ground, solidarity networks, women’s care and safety lines, ecological resistance, and cultural production, a multilayered fabric of resistance emerges. The goal here is not merely to “stay connected,” but to share the tools for building a just and free future together.

Every step taken against digital colonialism in Palestine forms part of today’s living struggle for liberation. When these practices intersect with the street, institutions, and networks, they not only gain visibility but evolve into a transformative political force. Our task is not simply to observe these experiences, but to create with them, expand them, and collectivize them—across labor movements, academia, professional associations, and local communities alike.

Today, there is a concrete call for all those who speak in the name of freedom: support local initiatives that sustain connection; contribute to archives and verification networks that resist censorship; scrutinize contracts, investments, and supply chains within our institutions; and strengthen mechanisms of boycott and accountability. Because for Palestine’s freedom—across the digital sphere, the streets, workplaces, and international channels of solidarity—there remains much to be done, and the time to expand that line of resistance, wherever we are, is now.

Footnotes

[1] Undoubtedly, what we have discussed here represents only a fraction of the ongoing struggles. As we continue to follow and research, new examples keep emerging before us.

[2] Marwa Fatafta, Ali Sibai, Zach Rosson, Kassem Mnejja, Hanna Kreitem, Sage Cheng, “Palestine unplugged: how Israel disrupts Gaza’s internet”, Access Now, November 10, 2023.

[3] Fatma Khaled “Internet and phone outage in much of Gaza disrupts humanitarian operations and deepens isolation”, AP, June 20, 2025.

[4] An eSIM is a digital SIM card embedded directly into a device, which can be activated remotely rather than requiring a physical SIM card.

[5] Heather Landy and Yasmin Shabana, “Tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza are staying connected to the world via donated eSIMs”, Quartz, March 20, 2024.

[6] Rasha Aly. “Palestinians in Gaza Using eSIM Cards to Get Around Communications Blackout”, The Guardian, December 17, 2023.

[7] Roberto Ferrer, “‘Network trees’: This Italian NGO helps keep Gaza connected to the Internet amid”. Euronews, July 2, 2024.

[8] Nidal Al-Mughrabi, “Hamas clamps down on Gaza’s ‘insecure’ Israeli SIM cards”, Reuters, November 17, 2016.

[9] World Bank, “West Bank and Gaza Telecommunications Sector Note”, 2008.

[10] Womanity, “Let’s Hear The Woman”.

[11] Elias & Yousef Anastas, “A Sonic Liberation Front from Palestine with Radio Alhara”, The Funambulist, November 2, 2021.

[12] Xerxes Cook, “The Sound of Solidarity”, Atmos, June 6, 2022.

[13] 7amleh, “Erased and Suppressed: The Impact of Digital Rights Violations on Palestinian Narratives Online”, December 18, 2024.

[14] Ali Abdel-Wahab, “Gaza’s Telecommunications: Occupied and Destroyed”, Al-Shabaka, February 4, 2025.

[15] Frontline Defenders, “Six Palestinian human rights defenders hacked with NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware”, November 8, 2021.

[16] Paresh Dave, “How Google Maps Makes It Harder for Palestinians to Navigate the West Bank”, The Wired, December 23, 2024.

[17] Amnesty International, “Israel/OPT: Israeli authorities are using facial recognition technology to entrench apartheid”, May 2, 2023.

[18] Asa Winstanley, “Israel tech site paying “interns” to covertly plant stories in social media”, Electronic Intifada, August 29, 2014.

[19] 7amleh, “The Palestinian Digital Rights Situation Since October 7th, 2023”, November 1, 2023. Adele Walton, “Social media users are bypassing censorship on Palestine, New Internationalist, January 31, 2024.

[20] Reham Hosny, Mohamed Nasef, “Lexical algorithmic resistance: Tactics of deceiving Arabic content moderation algorithms on Facebook”, Big Data & Society, 2025.

[21] Naomi Nix, “Pro-Palestinian creators use secret spellings, code words to evade social media algorithms”, The Washington Post, October 20, 2023.

[22] Human Rights Watch, “Meta’s Broken Promises: Systemic Censorship of Palestine Content”, December 21, 2023, Richard Luscombe, “Meta accused of censoring pro-Palestinian posts on Instagram and Facebook,”, The Guardian, December 21, 2023.

[23] Elizabeth Dwoskin, Gerrit De Vynck, “Facebook’s AI treats Palestinian activists like it treats American Black activists. It blocks them”, The Washinton Post, May 28, 2021.

[24] Diyar Saraçoğlu, “Júlia Nueno: Devletin ‘hakikat’ inşasını sorguluyoruz”, bianet, in Turkish, April 20, 2025.

[25] We also spoke with Rasheed Abueideh and wrote about Dreams on a Pillow: “Bir bilgisayar oyunu ile Nakba hafızasını geri çağırmak”, bianet, in Turkish, January 7, 2025.

[26] Francesca Albanese, “From economy of occupation to economy of genocide”, UN Human Rights Council, 59th Session, July 2, 2025..

[27] BDS, “No Tech for Oppression, Apartheid or Genocide”.

[28] Anonymous Google and Amazon Workers, “We are Google and Amazon workers. We condemn Project Nimbus”, The Guardian, October 12, 2021.

[29] No Tech for Apartheid, “No Tech For Apartheid Statement from ‘Nimbus 9’ Arrestees”, April 17, 2024.

[30] No Tech for Apartheid, “STATEMENT from Google workers with the No Tech for Apartheid campaign on Google’s mass, retaliatory firings of workers”, April 18, 2024.

[31] Michael Sainato, “Workers accuse Google of ‘tantrum’ after 50 fired over Israel contract protest”, The Guardian, April 27, 2024.

[32] Diyar Saraçoğlu, “Tarık Rauf: Apple’ın soykırımdaki suç ortaklığını anlatıyoruz”, bianet, in Turkish, October 5, 2024.

[33] Diyar Saraçoğlu, “‘Filistin İçin Teknoloji’ oluşumunun kurucularından Paul Biggar ile söyleşi”, bianet, in Turkish, August 6, 2024.

(DS/VC)