"Our native land is Greece. Our land of citizenship is Türkiye," Esat Ergelen, vice president of Lozan Mübadilleri Vakfı (Lausanne Emigrants Foundation), explains in his office, hidden in a side street of İstanbul's Beyoğlu district.

The foundation, set up in 2001, is one of the few organizations trying to research and uphold the history and heritage of those who forcefully migrated from Greece to Türkiye in 1923. At the time the countries' officials and the international community deemed it a necessary pact to 'normalize relations', 'bring tranquility to the region', and 'unmix of peoples' after years of war and struggle.

At breakneck speed, 1.2 million Greek Orthodox residing in the newly formed Republic of Türkiye and around 400.000 Muslims in now Modern Greece were uprooted. To live in places they had never visited, next to people they often had nothing in common except for religion. Some spoke the language of their new country fluently, others had an accent, and some did not all. One hundred years later, these past tragedies still stalk the region.

Turkish national identification pot

In Greece, the population change meant that the country had to absorb 1.2 million new citizens in a country of 5 million people, severely impacting its national and cultural fabric.

This was evident in the era's music, such as rebetika. This musical expression, born out of the exchange, serves as a testament to those tumultuous times by reflecting the emotional scars of the dispossessed in a melodic mix incorporating both Turkish and Greek Anatolian vernacular.

However, where in Greece, the event's magnitude was impossible to overlook, oppressive assimilation policies and the struggles for survival kept Türkiye's first two generations of mübadil (exchangees) mainly silent.

At the onset of the newly constituted republic, the state, instead of directly confronting the remains of its imperial past, opted to bury everything that could disrupt its newly formed national identity.

Assimilation campaigns were set up to force people to speak Turkish, and laws were enacted to punish the 'insulting of Turkishness'.

Articulating dissidence was actively discouraged in both public and private life. Hence, the mübadil were expected to melt into the Turkish national identification pot and to "forget the exchange."

Now, with the past slowly opening up for questioning, its third generation seeks to piece their family histories and cultural heritage together through photos, stories, songs, recipes, conferences, and excursions.

.jpeg)

Esat Halil Ergelen of the Lausanne Emigrants Foundation

Mahmutbey

In Ergelen's office, covered with pictures and posters of exchanges and events of the Mübadil, he elucidates that the idea of creating a foundation emerged in the 1990s as the first generation started to pass away. Additionally, this period marked the mainstream introduction of the internet.

"Internet had also just entered the world, and I decided to open a website. In order to make sure that their struggles and difficulties in building up a new life here were not forgotten," Ergelen explains, who himself is an İstanbul born third-generation Mübadil.

As part of the exchange, his grandparents moved from Naipli, a small village in rural Greece, to Mahmutbey. A small village at the time, but nowadays, part of suburban İstanbul's Bağcılar district along the E-80 highway holding home to the large İstoç trading center.

Mahmutbey was mainly inhabited by expelled Rum (Orthodox citizens living in the Ottoman Empire and Türkiye). Their places were filled with incoming migrants, a common practice by the government during the exchange.

The Mübadil's new occupations would be picked according to their place of origin. Ergelen's grandparents' area was known for tobacco, so they became tütüncü (tobacconists). Others became farmers, grape growers, or dealers in olives.

.jpeg)

''I didn't feel like a stranger''

His grandparents would never return to their place of birth, and Ergelen never thought about going to Greece, as the 'propaganda surrounding Greece and the Greeks' affected him.

However, diplomatic relations revitalized between Greece and Türkiye due to a series of devastating earthquakes that struck both countries in 1999, while the passing away of his grandparents evoked a yearning for his heritage.

"In 1994 my grandfather died, and in 2000 my grandmother. I felt rootless," Ergelen describes. In 2001, together with the foundation, he finally decided to go to Greece.

When he found his ancestor's village, it was not the garden of Eden as told by his grandparents. ''It was more like a Balkan village.''

A short time after going around Naipli, inhabited these days by only a couple of families, he started to feel something different, like this was his homeland.

"I walked around and thought a bit. Then, I realized that I didn't feel like a stranger here. I felt inside an incredible sense of peace."

Nevertheless, sadness took hold of him, "before going to Greece, I went to many different places like the US, China, and Singapore. But I never went to this place, so close to me," Ergelen explains, expressing remorse that he did not visit the place when his grandparents were still alive.

Furthermore, he was astonished to be able to speak Turkish with the people in the village.

"I went to my village in Greece. But they all spoke Turkish." Ergelen enthusiastically describes, while opening up a video on his laptop showing footage of an old woman in Naipli singing a Türkü, an oral tradition of folk poems sung in Turkish. "My father and grandfather knew the same Türkü's."

Bu gönderiyi Instagram'da gör

Just like his grandparents settling in homes abandoned by Rum in Mahmutbey, Greek immigrants from Türkiye relocated to Naipli.

''Then there was this old person called Esirbeyoğlu,'' he continues, who, in a Yozgat accent, explained to him, "When we lived in Türkiye, they called us Rum. Here they call us Turks."

"We lived the same pain and can understand each other very well. We are two sides of the same coin," Their stories are the same as those of my grandfather. That's why in the last twenty years, I go there and come back," Ergelen says.

However, this is becoming increasingly difficult with recent economic woes and visa issues. Consequently, on the occasion of the exchange's 100th anniversary, the foundation appealed for simplifying the visa process, aiming to prevent a recurrence of the hardships associated with these exchanges.

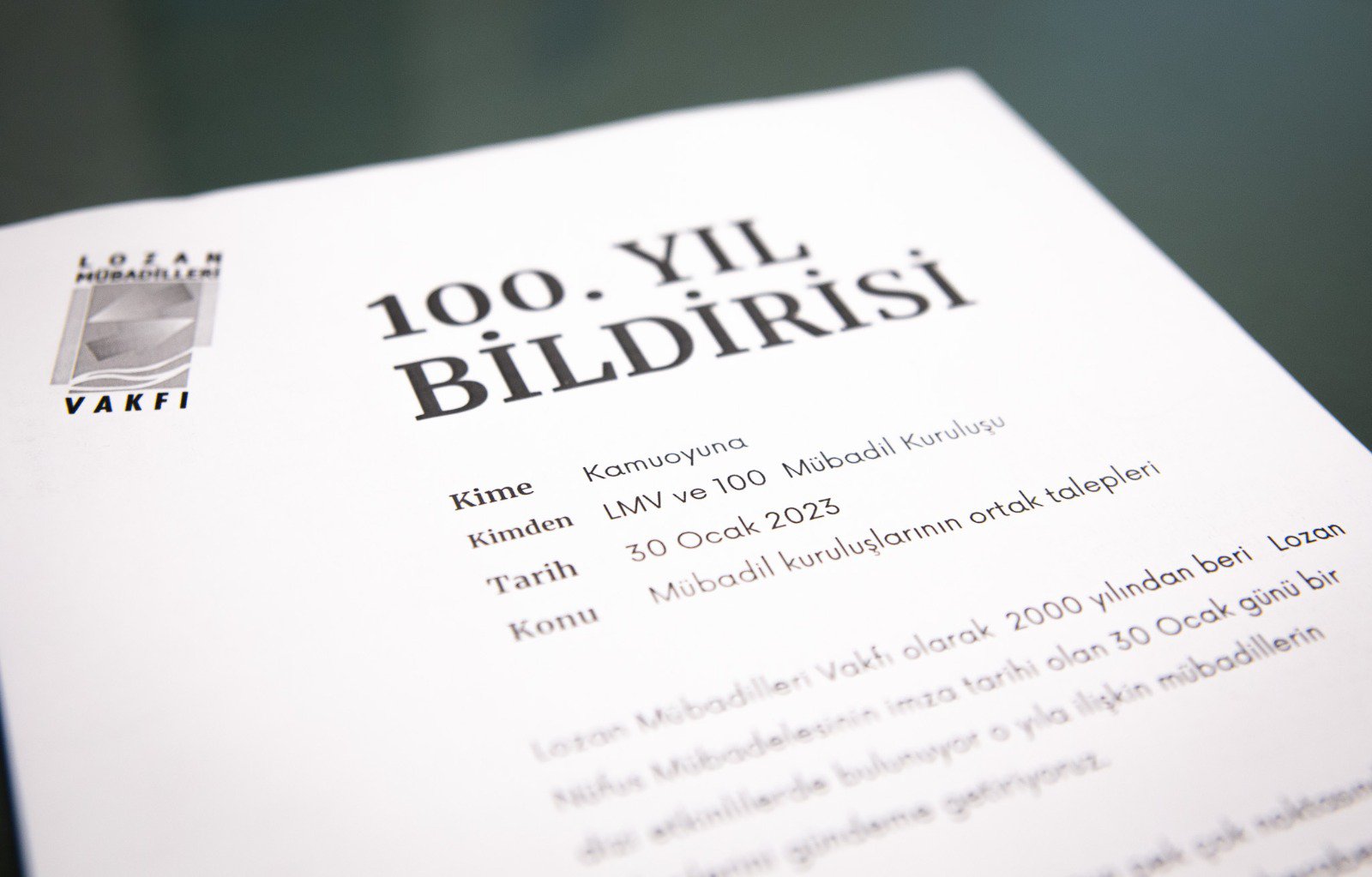

The 100th-year anniversary statement by the Lausanne Emigrants Foundation

(WM)

.jpg)

as.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)