Predictions about short-term politics are almost always unreliable. They require constant attention to political actors, daily monitoring of statements and subtexts, and endless speculation about shifting possibilities. This task becomes even more confusing in contexts where political actors claim decisive influence without actually possessing it. In such moments, clearer understanding is often gained not by following words, but by situating events within a broader historical and systemic perspective; one grounded in long-term structures rather than daily rhetoric. This difficulty is especially visible today in Turkey, where intense speculation about negotiations, leadership struggles, and state power often obscures the deeper transformation underway.

This essay follows that approach. It first outlines the historical and global context of the present moment, then draws comparisons with earlier periods of systemic rupture. It subsequently turns to the Kurdish question and the renewed negotiation process between the Kurdish freedom movement and Turkish political actors, before cautiously outlining possible trajectories emerging from this conjuncture.

I. Where are we?

Since the collapse of the Soviet system in 1990, the Middle East and the wider world have been undergoing slow, chaotic, and unpredictable transformations. Increasingly, our present moment resembles that of 1919, immediately after the First World War, when the former Ottoman territories were dismantled and redesigned. Today; Turkey, Iran, Syria, Iraq, and the surrounding region are passing through a comparable shakeout; one in which established political forms are losing coherence while new ones have yet to fully crystallize. Instability, contingency, and violence -hallmarks of the post–First World War period- once again shape the present.

This situation invites reflection on recurring historical patterns such as cycles consıst of approxımatelz 100 years. This is not a deterministic claim, but a heuristic way of thinking. If such patterns can be identified, they tend to operate across different temporal scales—long, medium, and short—each with distinct dynamics. These patterns should not be understood as laws of history, but as analytical lenses that help identify recurring structural pressures during periods of systemic crisis.

From this perspective, the First World War finds a contemporary parallel in the Arab Spring that began in 2011, not in terms of ideology or aspiration, but in their shared function as moments of systemic rupture. In both cases, the disintegration of established political orders created conditions in which existing institutions were reconfigured and mobilized to exercise extreme forms of violence. The Armenian Genocide stands as one of the most extreme historical expressions of this dynamic: mass violence carried out through state institutions whose legal and administrative frameworks were reshaped under conditions of imperial collapse. A century later, the brutality of ISIS -public executions, slave markets, and ritualized cruelty- represents a contemporary manifestation of a similar structural logic. Without implying direct equivalence, both cases reveal how, during periods of profound systemic disintegration, institutions themselves can become vehicles for unbounded violence, operating under narratives of survival, purification, or historical destiny.

This reading, in a broader cyclical perspective, resonates with Immanuel Wallerstein’s argument that we are living through a period of systemic chaos. Writing in 1999, Wallerstein argued that the capitalist world system had reached its geographical and structural limits and was entering a prolonged crisis in which the old order could no longer reproduce itself, while the contours of the new system would remain uncertain and contested. He suggested that this transition -initiated by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990- would take approximately four to five decades. The outcome, he warned, was not guaranteed to be more just or more stable than what preceded it.

From today’s vantage point, this diagnosis appears prescient. The transformation is not confined to the Middle East but encompasses the global system as a whole. Politically, we are witnessing a growing erosion of binding norms and rules, particularly among powerful states. Economically, volatility has become the norm. Long-standing pillars of the post-1970s monetary order -established after the United States depegged the dollar from gold- are under increasing strain. Soaring public debt, financial instability, and the renewed attraction of gold as a reserve asset signal not an immediate collapse, but a profound loss of confidence in the existing order. The sharp rise in gold prices in 2024 and 2025 should therefore be read less as a cause than as a symptom of deeper structural unease.

In short, the global system is changing slowly but chaotically, marked less by sudden collapse than by prolonged instability. When attention shifts from the global to the regional level, these systemic fractures become more concrete and politically consequential. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Middle East, where the upheavals unleashed since 2011 have not only redrawn borders of power but have also destabilized the very forms of statehood inherited from the twentieth century. Across the region, centralized nationalist states are struggling to reproduce themselves, while new forms of authority -military, sectarian, economic, and transnational- compete to fill the resulting vacuum. It is within this unresolved regional reconfiguration that Turkey’s current trajectory must be located: not as an exception, but as a particularly intense and revealing case of a state undergoing regime transformation under conditions of systemic crisis.

II. Negotiation amid regime breakdown

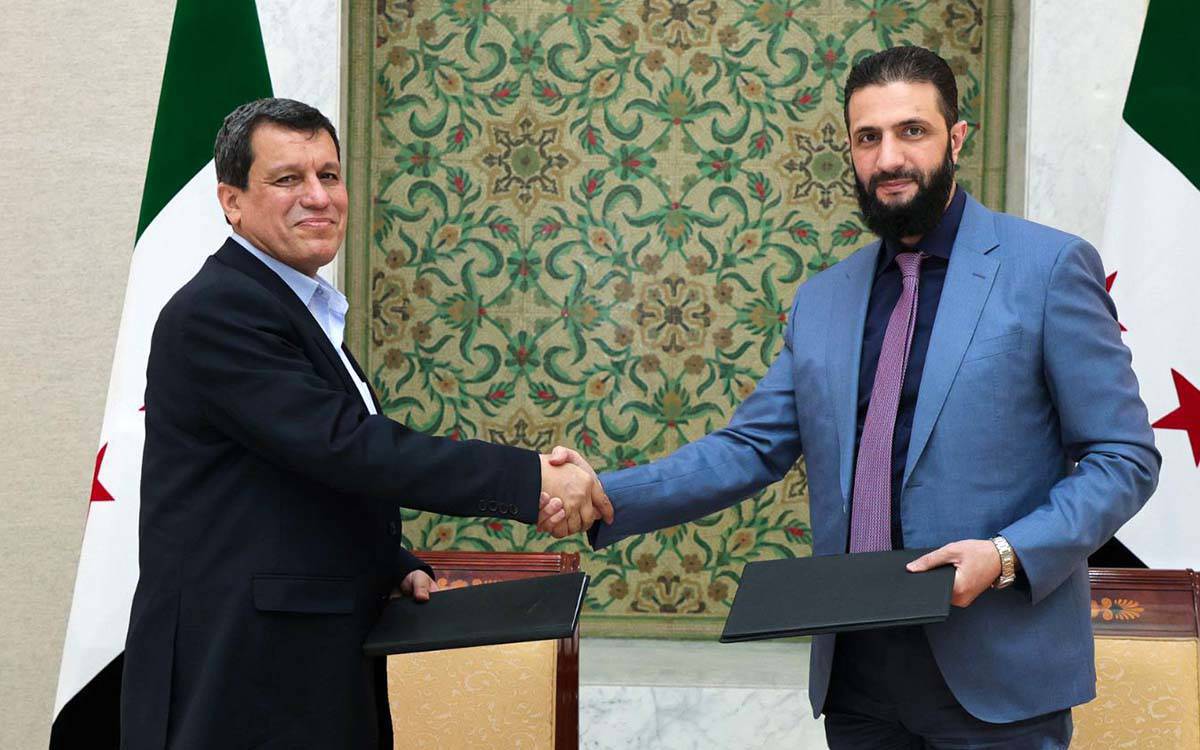

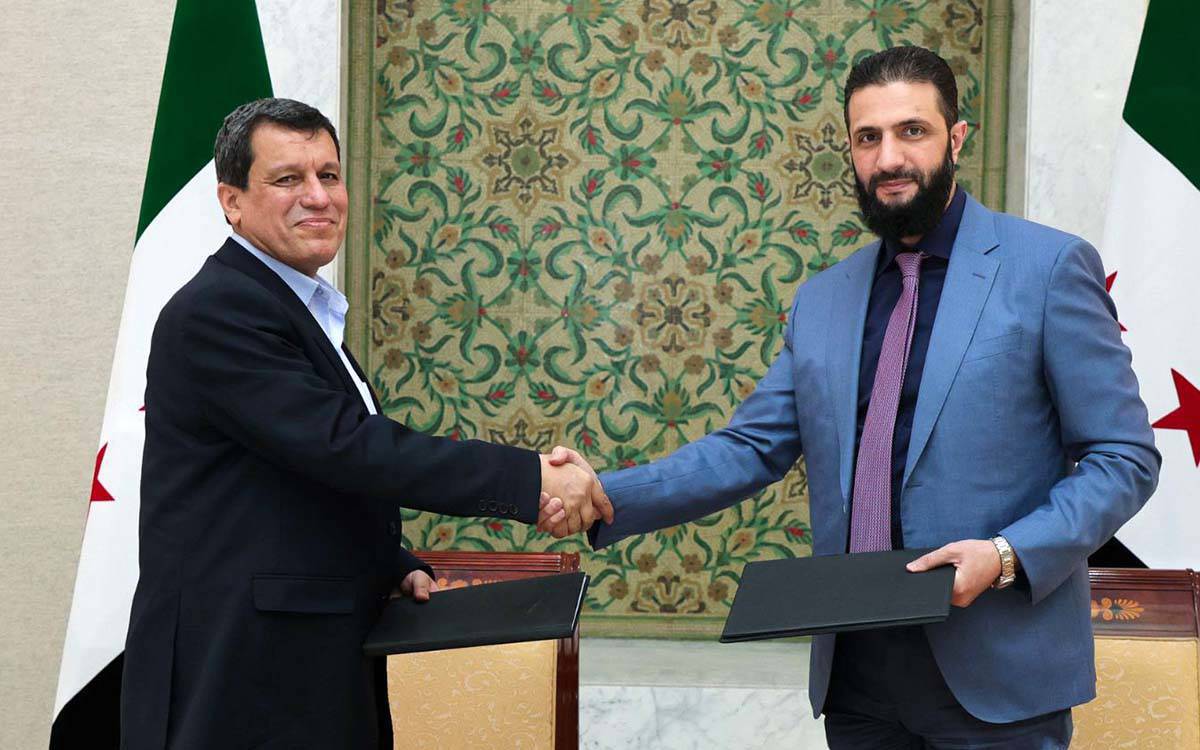

Within this broader regional and global context, a negotiation process has been unfolding between Turkey and the Kurds, led by the far-right Turkish politician Devlet Bahçeli and Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdish Freedom Movement. The negotiation process has opened a new and deeply uncertain phase, one in which confident prediction is impossible.

Initiated in October 2024 following Bahçeli’s call, the process has so far advanced cautiously in a generally positive direction, despite the Turkish government’s failure to take concrete confidence-building steps. At the center of this impasse stands President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who appears deeply unwilling to advance the process yet lacks the political capacity to openly reject it. Instead, he has sought to slow it down, an approach that risks pushing the entire process toward collapse.

To understand this tension, it is necessary to examine the transformation of the Turkish state itself. From the outside, the state projects an image of unity, strength, and centralized control; indeed, even over-centralization under Erdoğan’s presidential system. Beneath this hardened shell, however, lies a decomposing administrative body in which coherence, predictability, and institutional responsibility have given way to improvisation, factionalism, and personalized rule. What is unfolding is not simple institutional breakdown, but a regime-transformative process through which the old republican order is being dismantled while a new one struggles to take shape.

Since 2015–2016, Turkey has no longer functioned as a unified state in the classical institutional sense. The period from 2015 to 2023 was marked by the collapse of the earlier peace process, the July 2016 coup, and years of governance characterized by exceptional measures and legal arbitrariness. The result was the systematic erosion of institutional norms. What emerged was not a coherent state structure, but a fragmented configuration of power centers orchestrated around Erdoğan. While the external shell of sovereignty was preserved -and even hardened- the internal administrative logic was progressively stripped away. This fragmentation does not signal collapse, but transition: the destructive phase through which the old regime has effectively come to an end.

As a part of cyclical analysis outlined above, a comparable moment can be found in the late Ottoman period. On 23th January 1913, members of the Committee of Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terakki), including Enver Paşa, mobilized street pressure and carried out the Bab-ı Âli coup, forcibly entering the seat of the grand vizier, killing those who resisted, including the minister of war (Nazım paşa), and compelling Grand Vizier Kâmil Paşa to resign. Following this rupture, a narrow cadre governed the empire through informal power until its defeat in the First World War. In both cases, (1913-1918 and 2016-2023) legality was not overthrown by a mass revolution. Instead, it was hollowed out from within, as exceptional power gradually replaced institutional governance. The parallel is not one of intent or ideology, but of structure: a regime entering its terminal phase through lawlessness, concentration of power, and governance by a narrow circle operating under narratives of survival or greatness.

Since late 2023, a different process appears to be underway: the gradual formation of a new state framework. Regime transformations are rarely experienced as sudden ruptures. Even during moments of rapid change -such as the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 or the fall of the Berlin Wall- daily life often continues uninterrupted, with institutions functioning and actors recognizing the new order only retrospectively. Seen from this perspective, the claim that the Turkish Republic, in its twentieth-century institutional form, effectively ended in May 2023 is not an exaggeration but an analytical judgment. The system had already exhausted itself economically and politically; what followed was not continuity, but reconfiguration.

Within this emerging order, there appears to be little space for figures whose power rests on legal exceptionalism. Erdoğan’s role was decisive in dismantling the old regime, yet the new configuration taking shape is not necessarily compatible with his continued dominance. From this perspective, the claim that Erdoğan was “appointed” to ruin the Turkish state gains partial plausibility; not as an assertion of conspiracy, but as a retrospective reading of how structural necessity and personal ambition converged. He was not selected by hidden forces; rather, he was enabled to accelerate a transformation that had become structurally necessary. The twentieth-century Turkish state, shaped by nationalism and Cold War alignments, had grown increasingly dysfunctional within a Middle East undergoing long-term reconfiguration. Erdoğan thus functioned less as the architect of an emerging order than as the figure through whom the old one was dismantled.

Erdoğan’s political self-fashioning reflects this contradiction. In rhetoric he admires Sultan Abdülhamid II but imitates Enver Paşa, the Committee of Union and Progress leader who helped depose Abdülhamid and dragged the empire into the First World War. Yet Erdoğan resembles neither figure as much as Joseph Fouché, the master survivor of the French Revolution, the symbol of instrumental self-interest, guided less by ideology or principle than by an acute instinct for self-preservation. Loyalty, morality, and doctrine remain subordinate to political survival.

Regardless of whether Erdoğan ultimately supports or sabotages the peace process, his historical function appears largely complete. He has been a destroyer rather than a builder, and his capacity to shape a durable future order is therefore severely constrained. This paradoxically increases the incentive to obstruct a process that could render him politically redundant. If the peace process collapses, Turkey risks entering a period of uncontrolled violence and fragmentation, from which Erdoğan himself would not emerge politically intact. If it succeeds, the outcome may resemble a negotiated transition, comparable in certain respects to South Africa’s. Such analogies have limits, but they underline a central point: a successful transition would redefine political roles, leaving little space for figures associated primarily with destruction rather than reconstruction.

Conclusion

Taken together, the global systemic rupture, the regional reconfiguration of the Middle East, and the internal disintegration of the Turkish state form the backdrop against which the current peace process must be understood. Turkey is being reshaped through and alongside these broader transformations, and the peace process is not merely a political choice but the point at which an ongoing transition must crystallize into a new regime. Yet within a system hollowed out by legal exceptionalism and institutional fragmentation, such a process also constitutes a structural threat: any attempt to establish legal clarity, institutional coordination, and predictable authority inevitably exposes the underlying decay of the state itself.

The Kurdish question stands at the center of this conjuncture, determining whether the emerging order will take a more inclusive or a more exclusionary form. Should the peace process succeed, it will almost certainly produce a new state framework, more flexible than the existing republican model and potentially accompanied by constitutional change, nd being open to further alterations.. Should it fail, the transition will not be halted but violently displaced. In either case, the Kurdish question will define the character of Turkey’s next regime. The only remaining uncertainty is not whether a transition will occur, but how much destruction will accompany it. (SRD/VK)