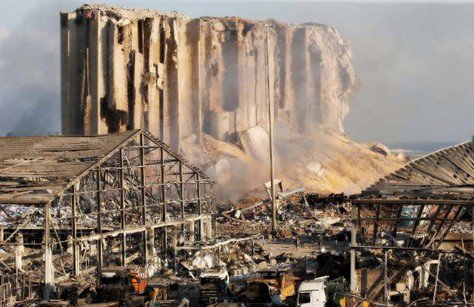

* Photo: Anadolu Agency (AA)

Click to read the article in Turkish

The question of "How did we end up like this?" is playing on everyone's minds in the Arab and Muslim world today!

What happened? Why did it happen?

Several opinions have been put forward; some have attributed this deliberation to the collapse of the Ottoman State in 1918, some have considered the 1967 Israel-Arab War to be the starting point, some have pointed to Iraq's occupation by the United States of America (USA) in 2003 and what happened afterwards... It has been discussed and written about so much; the Middle East has always kept on living as a tangle of problems, from the colonial past to the nation state.

We, the ones who live in the region, have come to these days by living through the Cold War, wars, coups, kings, authoritarian states, Islamic states, the republic, elections and, lastly, the "Islamic Jihad terror".

What has changed today?

If we consider it a period of nearly 103 years (1918-2022), we are talking about four generations: The ones who were born in the early, mid- and late 20th century and the ones who were born in the 21st century.

Turkey has seen itself as the true heir of an Empire; a multireligious, multisectarian, multilingual, multicultural structure that reigned over three continents. We are talking about an Empire where İstanbul, a unique city in which religions, languages, cultures bloomed and flourished for centuries, was the capital and which brought continents together! For four centuries of this history, the Arab geography had been under the Ottoman rule.

It was in the 20th century that they seceded from the Ottoman State and became independent states. This process was tough and had its ups and downs on the part of Arabs. Their relations with the Republic of Turkey were very different from those in the Ottoman era; they developed on the level of independent nation states.

'We'

I have written all these to explain the word "we" that I used in the beginning of my article. As a person who lived and worked in different cities of the Middle East and is in close relations with especially Lebanon and Beirut, I felt myself as "we" in these countries, rather than as a foreigner.

Perhaps the same feeling is also the case for the Balkan countries. Having a history, lifestyles, food and culture in common... For this reason, I see what is happening in Lebanon, what people go through and the sorrows and losses they suffer, which is the subject of this article, as "we".

Lebanon has been grappling with a grave economic crisis that broke out in 2015 and the crisis is still ongoing today. Before touching upon the reasons behind this economic crisis as well as the political structure of Lebanon based on sects, I would like to begin with today.

I was actually planning to be in Beirut on the days when I wrote this article. I could not go there after the horrible blast that happened in the port of Beirut in August 2020 and blew up a part of the city, leaving hundreds of people dead and thousands of others wounded.

Another trouble called COVID-19 was hovering over us; traveling was difficult and risky. By writing from afar, getting the news and enrolling in the courses offered by the "University for Seniors" special department opened by the Beirut American University for elders, I could follow what was happening there and how difficult days people were going through.

August 4, 2020/AA

Beirut

This year, trusting my vaccines, I wanted to stay there for some time and to see and live the sorrows of Beirut. I wrote to a very old friend of mine who still lives in Beirut, or tries to live, to be more precise, and said that I was coming. The response came quickly.

Are you sure that you want to come? The Beirut where you lived and that you know is not here anymore. Even the Beirut where you lived in the most difficult times of the civil war is not here anymore. The cafes where we sat across the Mediterranean and engaged in heated discussions are not here, either. Most of them have been closed. The days when we took to the streets in 2019 and shouted together against Lebanon's long-established order based on sectarian and ethnic identities, saying, 'Go away, go away you all', are also long gone. There is not even a state, a government in Lebanon anymore, we just go on and live. The most basic public services that you may think of such as electricity, water, rubbish collection, sewerage, are no more. I am sending you the link of an article penned by a young Lebanese woman translator and writer, Lina Mounzer. Read it and decide. Do you want to come to Beirut?

This answer from a friend who went through so many hardships over so many years, lost loved ones in the civil war, but still held on to life shocked me profoundly. I thought that I would definitely go there but I could not. COVID-19 or a similar disease confided me to home. I read Lina Mounzer's article while I was lying.

Women

Lebanon has been a very fertile land in terms of women writers, artists and filmmakers. Especially the women aged 35-55 talk about what they went through, the effects of war and the development of feminist movement through Beirut in a very powerful expression.

The main feature of women's expression is that in a field where men are more reserved, they are focused on the emotional world such as the individual's daily life, their reactions to the environment of violence and war that they are brought against, their sorrows, joys and rage.

Still dominating the politics in Lebanon and as the sole responsible ones for the current situation of the country, male politicians maintain a discourse that is comprised of limited words and does not say much in essence while they stay in a protected area that never touches them, sustaining their own comfort zones rather than developing solutions for problems.

In the face of women's audacious expressions that say "What else is there left to lose", an army of men saying "Just don't lose what we have"!

Lina Mounzer tells

"Lebanon as We Once Knew It Is Gone"

"I never thought I would live to see the end of the world.

"But that is exactly what we are living today in Lebanon. The end of an entire way of life. I read the headlines about us, and they are a list of facts and numbers. The currency has lost over 90 percent of its value since 2019; 78 percent of the population is estimated to be living in poverty; there are severe shortages of fuel and diesel; society is on the verge of total implosion.

"But what does all this mean? It means days entirely occupied with the scramble for basic necessities. A life reduced to the logistics of survival and a population that is physically, mentally and emotionally depleted.

"I long for the simplest pleasures: gathering with family on Sundays for elaborate meals that are unaffordable now; driving down the coast to see a friend, instead of saving my gas for emergencies; going out for a drink in Beirut's Mar Mikhael strip without counting how many of my old haunts have shut down. I never used to think twice about these things, but now it's impossible to imagine indulging in any of these luxuries.

"I begin my days in Beirut already exhausted. It doesn't help that there's a gas station around the corner from my house. Cars start lining up for fuel the night before, blocking traffic, and by 7 a.m. the sound of blaring horns and frustrated shouting from the street is fraying my nerves.

"It is nearly impossible to sit down to work. My laptop battery lasts only so long anyway. In my neighborhood, government-provided power comes on for just an hour a day. The UPS battery that keeps the internet router working runs out of juice by noon. I'm behind on every deadline; I've written countless shamefaced emails of apology. What am I even supposed to say? "My country is falling apart and there's not a single moment of my day that isn't beholden to its collapse"? Nights are sleepless in the choking summer heat. Building generators operate for only four hours before going off around midnight to save diesel — if they are turned on at all.

"Every few days there's a new low to get used to. One recent morning I needed to exchange some dollars to buy groceries, chiefly bread. At the exchange shop there was a long line of people because the dollar rate was slightly down. There had been rumors that the new prime minister was close to forming a government. At this point such news is like a joke — we've been without a government since the cataclysmic port blast on Aug. 4, 2020, and the three prime ministers delegated by Parliament to form a government since then have failed to do so because of infighting between political parties, the same ones who've brought this country to ruin. Still, all markets are susceptible to rumor, and whenever the dollar rate goes down, people flock to convert their useless Lebanese lira into dollars.

"Once I had my money, I headed to the supermarket, and on my way I encountered a tiny old woman sitting on the pavement. I wanted to give her some money and a bottle of cold water. I went to four shops before I found one. This was how I first learned that we are now also facing a shortage of bottled water. The week before, I'd discovered that there was a shortage of cooking gas after our canister ran out and I had to make a dozen calls — and pay five times what it once cost — to replace it. While cooking gas is vital, the shortage of bottled water is an even bigger disaster in a country where most Lebanese believe the tap water isn't even safe enough to cook with. (Tap water, too, is at risk of being shut down.) I read about it later: There isn't enough fuel to power the machines forming the plastic bottles or the pumps that fill them. No fuel for the trucks making deliveries."

Lina's article is long. It goes on. But I am exhausted.

Crisis

My house is warm. My water runs. My bed is clean. I have my cat with me!

While I am one the Internet at night, a Reuters news report catches my eye: "Lebanon's savers to bear burden under new rescue plan".

Lebanese administrators offered a solution to close the huge gap opened in the financial system of the country as a result of their own politics. To close it, the savings of not the state and banks, but people will be used!

The plan will reportedly seek to revive the moribund banking system of the country by making depositors cover more than half the 69 billion dollar gap, which is three times the size of Lebanon's economy. It will include converting a large portion of dollar deposits to Lebanese pounds at rates that wipe out much of their value. The state, central bank and commercial banks will contribute 31 billion dollars, or less than half.

As reported by Reuters, savers in Lebanon with less than 150,000 dollars will have dollars preserved - amounting to about 25 billion dollars - but, like other depositors, the money will be paid out over 15 years!

"The Lebanese pound, which before the crisis was exchanged at 1,500 to the dollar, now trades around 20,000."

I turn off the computer and close the lights.

The voice of Sezen Aksu fills my room:

I don't even have a cat

Do you understand

Come on, smile!

(MUT/APK/RT/SD)