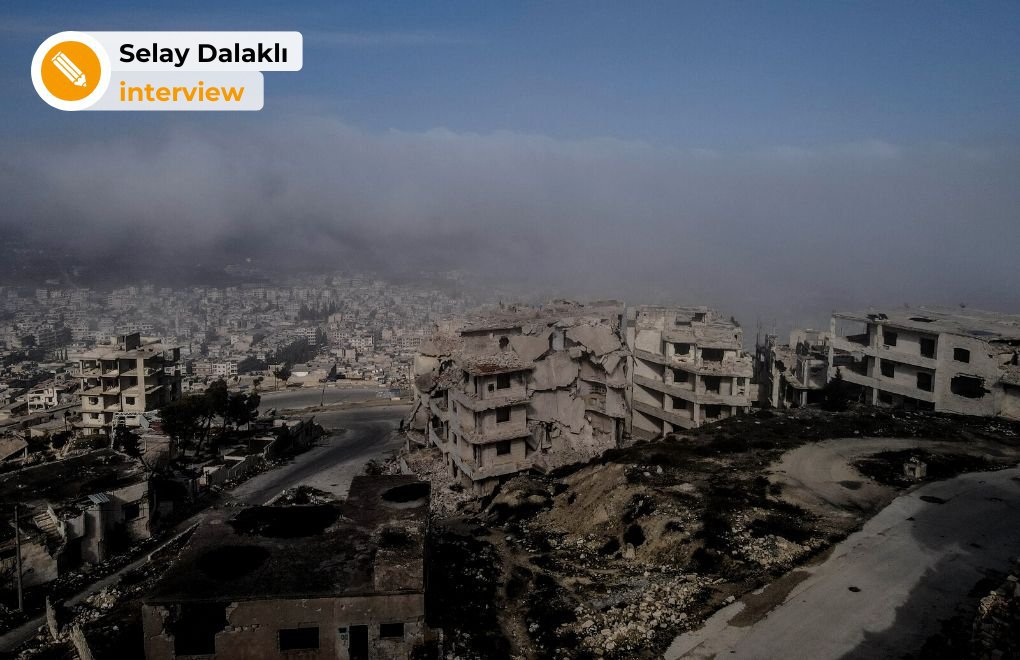

* Photo: Murat Bayram

Click to read the article in Turkish

* The speech made by bianet English editor Selay Dalaklı at the "Editors for Trust" forum held in Montenegro as part of the Resilience project.

When I hear the expression "constructive journalism", I really cannot help thinking about or remembering what kind of a mediascape we have in Turkey. Because I think what we have back there – in the general sense of the term – is anything but constructive.

But I still believe that as a person working for a rights-based media outlet, I can share my – or our – own experience of peace journalism at bianet as an example of how constructive journalism can possibly be practiced in a context which is marked by an ever mounting judicial, administrative and political pressure on the exercise of rights and freedoms.

CLICK - bianet news on peace journalism

As I have said, we, at bianet, embrace peace journalism, along with rights-based journalism, as one of our guiding principles.

To offer a rather broad definition for the term as we understand it, peace journalism is news reporting of any sort of tension, conflict or hostility in a resolution-oriented manner without inciting violence.

Here, news tries to offer a comprehensive picture of the situation by asking how the conflict developed, its causes, the positions of all sides and on what options they might agree, rather than differ.

More importantly, it shows that there are non-violent responses to conflict, which can be considered and valued. It does not only hear or reflect the official voices or numbers, but listens to those who are or may be affected by the conflict and in what ways they are affected.

Moreover, peace journalism does all these with a "the other"-centered ethics, which means it considers that there will always be "the other" of "the other". For instance, if there are refugees, then, there are also women refugees and there are also LGBTI+ refugees. So, peace journalism speaks with the ones whose voices are not heard.

I think this is something that deconstructs and questions the established principles and codes of conventional journalism just as it deconstructs and questions the conventional definition of peace.

Because it offers a positive definition of peace, rather than a negative one in the sense that peace is not solely the absence of war or conflict, but a state free from all types of structural and cultural violence which is – most of the time – coupled with discrimination, hate speech and hate crimes.

And this makes these principles applicable in almost any context.

***

But, speaking of peace... Peace has always been a loaded word in Turkey. It is not always easy to side with or show that you side with peace and resolution in the face of conflicts and violence.

I think the closest Turkey got to peace and peace journalism was – in fact – during the Resolution Process for the Kurdish question from early 2013 to mid-2015. At first, this process seemed to be a turning point for both peace and its journalism in the country.

Because all of a sudden Turkey and its mainstream media seemed to discover that peace was actually something good. When we look at the news back then, we see that especially in the newspapers close to the government, which initiated the Resolution Process in the first place, their headlines read like "Now is the time for peace", "Call for a farewell to arms", "Giant step to peace", etc. That was not something we were familiar with in the mainstream media.

It was good. But this pro-peace and pro-resolution narrative disappeared as suddenly and quickly as it came up. Soon it turned out that this change in the discourse of the mainstream media did not really reflect a change in their understanding of journalism or it did not mean that they embraced peace journalism as a guiding principle, but rather, they just reflected the change in the discourse of the government or of the ruling party.

So, when the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) was pro-peace, so were they. When the AKP was not anymore, neither were they.

That was why media ombudsperson Faruk Bildirici, one of the participants of bianet's Peace Journalism workshop in April 2015, said, "Actually, life imposed something about peace journalism in Turkey. [...] But that has not been internalized within the editorial processes."

That is also why Sevilay Çelenk, a dismissed Assoc. Prof. from the Ankara University Faculty of Communication, has recently said, "The Kurdish issue is actually a media issue. [...] In fact, the ways in which the deaths of Kurds are reported in the media are felt as a second death by Kurds. There is a divide between the media and the reality for them."

And now, six years after the end of the Resolution Process, we are doing journalism in a mediascape which is marked by anything but rights-based journalism and which is full of polarization, hate narratives and discrimination against any person or group that lives or thinks differently, from refugees to women and LGBTI+s, from Kurds and Armenians to Greeks, Jews, Alevis.

On the one side, there is a mediascape marked by the concentration of media ownership in the hands of a few pro-government groups and, on the other, a few critical media outlets, mostly online, facing a mounting judicial, administrative, political and economic pressure.

It is in this context that we are trying to do peace journalism, along with rights-based journalism, in Turkey, together with a few other media outlets.

***

So, how do we do it? I mean, how do we try to ensure that our news remains resolution-oriented and constructive?

I think the reporting of refugees and migration, especially since early 2020, is a good example in that regard.

Just to refresh our memories about what happened back then... On February 27, 2020, 34 soldiers of Turkey were killed in an airstrike in Syria's Idlib. A day later, the government, which had secured a so-called refugee deal with the European Union (EU), announced that Turkey would open its borders for the refugees who wanted to cross into Europe. With this announcement, hundreds of refugees headed for Turkey's northwestern borders.

According to Turkey's Immigration Authority, as of September 2021, there are over 3.71 million Syrians under temporary protection status in the country. And already in 2019, Syrians were the second most frequently targeted group in Turkey's media with 760 hate speech items, as documented by the Hrant Dink Foundation in its annual report.

This airstrike in February 2020, coupled with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey in March 2020 and the ensuing economic crisis and unemployment, aggravated the situation even further. It is now not surprising to see news, in the pro-government and critical media alike, which puts the blame on refugees for any social or economic problem that might occur.

What is worse, this goes hand in hand with actual, physical attacks, such as the ones targeting the houses and shops of refugees in Ankara in mid-August. And the response of the state to this was to announce that the capital city was now closed to the registration of new refugees.

***

So, how do we report on migration and refugees within such a context?

In early February 2020, when people were heading for border gates, our human rights and freedom of expression editors went to the Turkey-Greece border to report on the situation of refugees. As we did not want our reporting to be limited to official statements, numbers and – in fact – all this dehumanizing discourse, they directly talked to people there.

They shared human stories. They asked people what kind of a life they had in Turkey, why they wanted to go to Europe in the first place and what kind of problems, hardships and violations of rights they faced in Turkey as well as in Greece after or if they somehow managed to cross to the other side. They helped the public hear the voices of refugees instead of solely covering the statements of those speaking on their behalf.

Moreover, their reporting did not act like "the Syrians" or "the refugees" were an indivisible, homogenous whole. They talked to women, to the young, they talked to people who fled various countries such as Afghanistan, Somalia or Pakistan and they wrote their impressions based on this.

CLICK - Two Countries, One Border: Limbo

CLICK - 'They Take Our Money, Beat and Send us Back to Turkey'

In the meanwhile, bianet newsroom in İstanbul was reporting on how disadvantaged groups such as women, children and LGBTI+ refugees were or might be affected by this recent wave of migration, asking different shareholders such as NGOs, rights organizations or bar associations how these hardships and problems could be solved or – at least – alleviated.

In fact, all these points that I have talked about also characterize our reporting on migration and refugees in general.

So, we ask how refugees have been affected by the pandemic or whether their children have had access to distance education during the pandemic; we are problematizing the exploitation of their labor in precarious jobs and unregistered employment; we are voicing the problems and hardships faced by refugees with disabilities and trying to offer solutions...

In doing this, we also try to shed light on hate speech and discrimination against refugees in both politics and media as well as among the public.

***

As I have said, considering the current mediascape in Turkey, it is really hard to talk about a general practice of constructive journalism just as we cannot really talk about a widely embraced practice of peace journalism or rights-based reporting in the country.

But I think there is still some good news or some source of hope.

As it is also indicated in bianet's Peace Journalism Handbook from the year 2016, there are a series of countries where peace journalism is indeed practiced, without remaining on paper, such as Ireland, Uganda, the Philippines, Indonesia, Nepal, Afghanistan, Serbia, Israel and Rwanda.

And these countries have something in common: They experienced conflicts, ethnic, religious or sect-based tensions or even a civil war and these experiences have led them to see the media's negative role in those times and led many to make a choice for peace journalism in the end.

And we now hope that the number of journalists and media outlets that make a pro-peace choice with such an understanding will also increase in Turkey and elsewhere in time.

About the Resilience projectAs part of the "RESILIENCE: Civil society action to reaffirm media freedom and counter disinformation and hateful propaganda in the Western Balkans and Turkey" project, media development organizations in the Western Balkans have joined forces with the IPS Communication Foundation/bianet. The three-year project is coordinated by the South East European Network for Professionalization of Media (SEENPM), a network of media development organizations in Central and South East Europe, and implemented in partnership with: Albanian Media Institute in Tirana, Foundation 'Mediacentar' in Sarajevo, Kosovo 2.0 in Pristina, Montenegro Media Institute in Podgorica, Macedonian Institute for Media in Skopje, Novi Sad School of Journalism in Novi Sad, Peace Institute in Ljubljana, and bianet in Istanbul. The project is funded by the European Union (EU). |

(SD)

.jpg)

.jpg)

132.jpg)

.jpg)