Between 2014 and 2015, the Kurds—especially woman militants—were placed at the center of the global public’s moral narrative. The fight against ISIS was classified by the West as a “just war,” and Kurdish fighters became embodied representations of secularism, feminism, and sacrifice. The feelings of admiration, gratitude, and pride circulated in the media and intellectual sphere were, in Sara Ahmed’s terms, conditional emotional investments. The Kurds were loved, but this love did not turn into “attachment,” responsibility, or permanence.

Today, the fact that the same actors and the same practices of struggle have become liable to blame, particularly in Western media and among some state officials, is less about the emergence of new information than it is about the alignment of emotions with a new political line. As Ahmed emphasizes, emotions are not neutral; they shift direction with power. When admiration is withdrawn, what remains is not a void, but discomfort, distance, and accusation.

Germany-based Der Spiegel, in a report published on Jan 20 titled “What kind of game is the most powerful Kurdish militia in Syria playing?”, stated that Syria narrowly avoided a new civil war and that the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the country’s northeast were doing everything in their power to maintain control there, stressing that “the danger has not yet passed.” Since 2015, Der Spiegel has occasionally featured stories about YPJ women, sometimes in full-length reports and sometimes via quotations from other platforms. For example, in a 2015 article, the role of female fighters in the defense of Kobanî was conveyed in detail, and the symbolic and inspirational dimension of the movement was highlighted in the Western media.

UK-based Middle East Eye, in a report published on Jan 25, described the SDF as a controversial group, stating that it “is seen as the Syrian branch of the PKK and has long controlled the oil-rich regions of northeastern Syria in line with US and Israeli interests.” It also wrote that the US had ended its support for the group because its role in Syria had “largely come to an end.” In a 2017 article, it was emphasized that one of the biggest challenges facing the SDF in the post-ISIS period was not only coping with massive destruction, but also spreading a model of women’s rights to the conservative tribal regions of northern Syria and banning polygamy.

Following the attacks that began on Jan 6, declaring the Kurds or the SDF guilty has become the most functional way to eliminate the responsibility caused by the previously established moral bond. At this point, the concept of “emotional economy” becomes tangible: Emotions are circulated to distribute or cancel obligations. Silence, distance, and the language of balancing appear not as tools of neutrality, but as instruments of this cancellation.

Sticking or stuck emotions

Based on what I’ve read, heard, and seen: for the Kurds, this transformation is not only a political loss but also signifies a deep emotional repositioning. The emotion produced here is not a simple disappointment; rather, it is a hard fact about how the world works settling into the body again and again. To be recognized makes the subsequent withdrawal more painful. Not knowing someone’s existence, or knowing them from afar and merely greeting them when seen, does not hurt them; but acting as though one never knew or had a good relationship with them makes it harder to cope with the positive emotions once attached. Today, the world—except for the friends of the Kurds across the globe—is doing exactly this: It is not ignoring the Kurds, but changing its view of them, withdrawing its sense of responsibility and emotional bond, and trying to erase most of the positive emotions once attached to them.

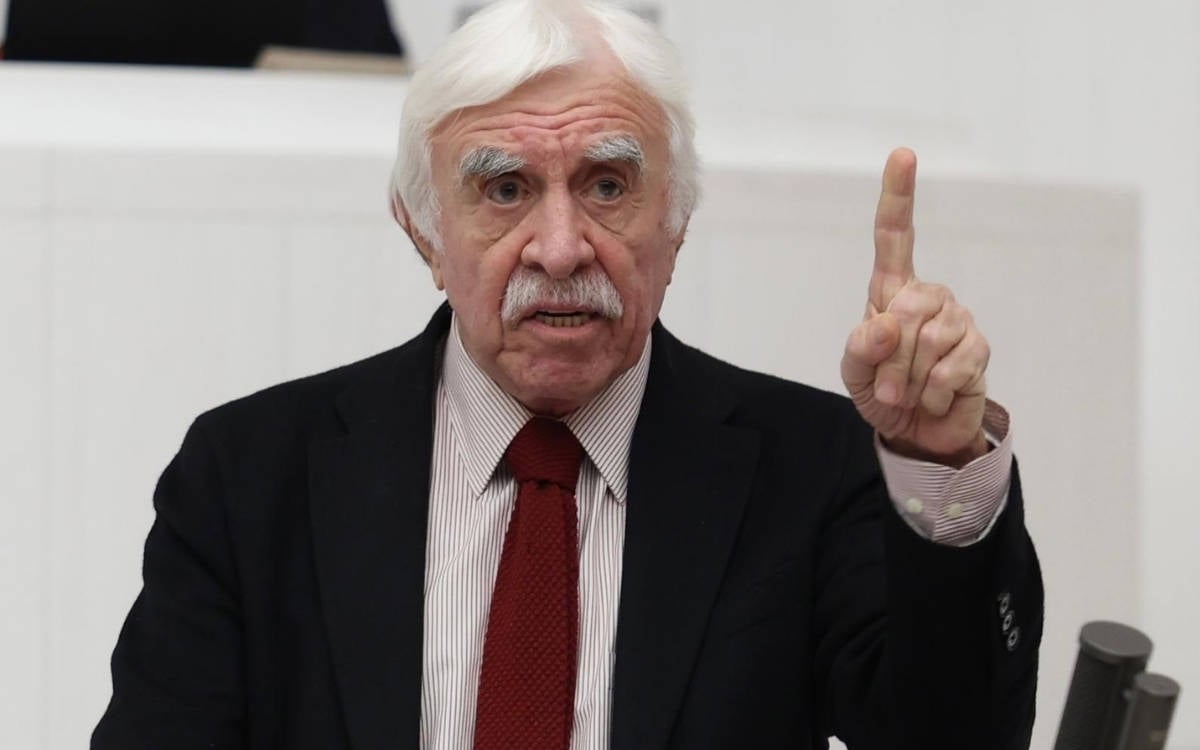

The co-chair of the Peoples' Equality and Democracy (DEM) Party, Tuncer Bakırhan, drew attention to the political reflection of these emotions in a way rarely seen in recent Turkey's politics, and did so with remarkable clarity:

I have been in the border regions for days. I have witnessed emotional fractures in the eyes of the Kurds deeper than anything I have seen in my life. The simplest yet deepest reason for this is the open injustice done to a people and the words and actions that trample on their dignity, which are matters beyond politics. The coarseness that sacrifices this fine threshold to politics has backfired throughout the history. This must be correctly understood. The Kurds see and experience the government’s dual policies not only in politics but in every moment of their lives. The ease with which some make calls for massacre on TV, the insults directed at the people and their representatives, the bizarre victory cries, the ones who try to put them in their place and wag their fingers... I address those who do not see the emotional rupture experienced by those you call your ‘ancient Kurdish brothers’: this is not a reproach; it is a historic fracture growing in the conscience of a people. The fracture is deep and, the more it is ignored, it grows quietly and with anger.

However, it is not possible to explain what is happening solely through the “cultural politics of emotions.” The Kurds functioned as an indispensable “local force” in the fight against ISIS in Syria. In this context, the admiration circulated in the media served as much as an emotional investment as it did a biopolitical function. The fact that the same figures have become so readily indictable in the Western media today does not stem from a sudden deviation in Kurdish political lines, but rather from a change in the needs of the empire. As Hardt and Negri have pointed out, the empire does not demand loyalty but conformity and obedience. When conformity is disrupted, that is, when the cost rises, those who were applauded yesterday can easily be declared “destabilizing.” At this point, the accusation turns into a reflex of the order to exonerate itself. Now, every fracture experienced in Syria, in the Middle East, or in global balances is explained by the Kurds being “too autonomous,” “too assertive,” or “too complex.” Thus, the structural contradictions of the system are placed upon the shoulders of a people. The concept of "manageable chaos" functions precisely at this point.

The Kurds are kept in a position both inside and outside the empire: They are active enough, but never full subjects. The moment they come close to self-determination, they become surplus in the eyes of the empire. The replacement of applause with accusation becomes a “punishment” for this transgression of boundaries.

History has shown time and again that even in the most hopeless moments, there exists a possibility that illuminates the mind. For the Kurds, this possibility is the very struggle for existence. The relationality that Kurds, who live primarily in four different countries, strive to build across borders is one of the contemporary manifestations of this existential form. This bond, made visible by banners reading “2+2=1” in squares around the world or by Ronahî TV and Rûdaw correspondents standing side by side, goes beyond the logic of the classical nation-state. What is being pointed to is not a central and hierarchical unity, but a horizontal, dispersed, and relational form of political subjectivity. This network reconstructed every day on social media through different Kurdish national anthems, resistance songs, and images of collective memory, carries a form that the empire cannot easily absorb, represent, or manage. The internationalist friends of the Kurds around the world have not only become witnesses to this network but also multipliers, placing it on a shared ground.

Ultimately, emotions will settle again; grief and anger will turn into a potential political power. What remains when applause is withdrawn and accusations are circulated is a persistence of existence that does not need the empire’s approval. Fragmented and fragile, but precisely for that reason difficult to manage. And perhaps this is the Kurds’ real “crime” today. A crime that perhaps transforms into a possibility right at this point: as they are pushed outside of history, they begin to construct their own time. (TY/VK)

Sources

- Der Spiegel, Kurdinnen in Syrien: Frauen an der Front gegen den IS Photo Gallery

- Middle East Eye, Kurdish fight for women’s rights faces challenges in Syria

- Middle East Eye, X post

- Der Spiegel, Welches Spiel die mächtigste Kurden-Miliz in Syrien

- Medyascope, Tuncer Bakırhan Medyascope’a Yazdı: Kırılma Giderek Büyüyor, 25 January 2026

- Sara Ahmed, Duyguların Kültürel Politikası, Sel Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 2019.

- Antonio Negri & Michael Hardt, İmparatorluk, Ayrıntı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2023.