"Facing the past," a relatively new concept for our country, should be taken as a serious issue for societies experiencing internal conflicts and needs to be studied by political elites. Briefly, it is accepted that facing the past implies keeping the past alive and being aware of the value of history and the cultural background of social groups. On the other hand, facing the past should not be considered a means of historical revenge, but rather as part of efforts to build a participative political system based on human rights and democracy. Moreover, analysis of the research and studies on facing the past justifies its historical value in the process of building a stable political system in multicultural societies.

In the last 20–25 years, with the emergence of the issue of facing the past, some changes have been observed in the assessment of traditional relationships with the past of cultural groups. This change is primarily seen in the criticism of the official narrative of national history and also in the rising demands for the revival of hidden and destroyed pasts. Briefly, these demands called for some work to help revive the past, such as encouraging academic research on the past, culture and identities, and the historical heritage of societies.

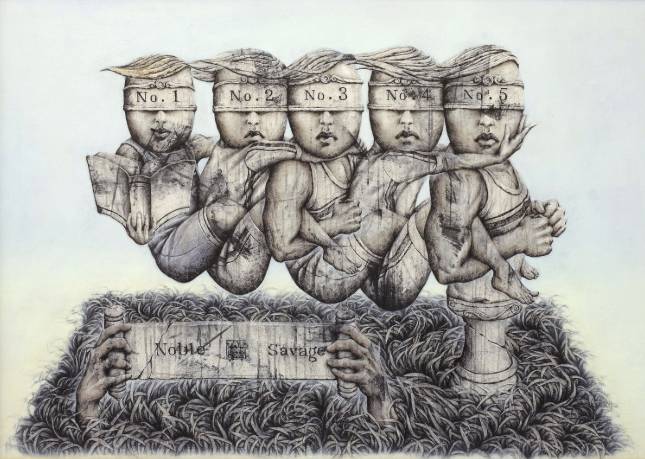

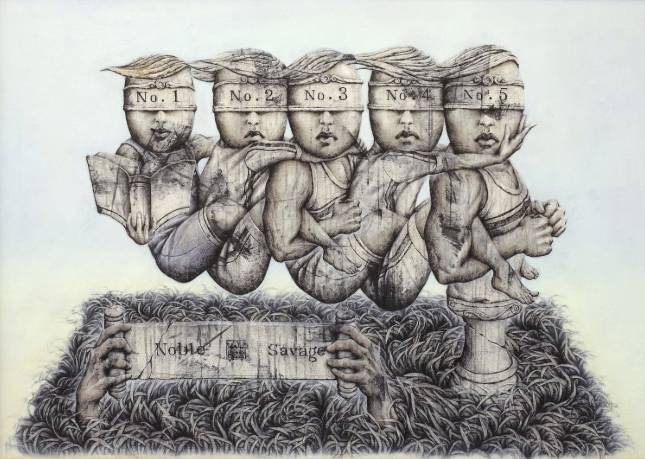

Raising awareness about history is hoped and expected to start questioning the unfair, illegal, and inhuman practices and crimes committed in the past. In other words, history can also be characterized by political conflicts, genocide, ethnic cleansing, forced labor, starvation through siege, mistreatment of prisoners of war, forced religious conversion, mass rape, kidnappings of children, oppression and executions of other ethnic and religious groups, and many other forms of gross injustices.

The term "facing the past" emerged in the 1950s, and Germany’s initiatives to face its own past in the 1960s encouraged researchers and academic institutions to study the topic. In the 1990s, the studies on this subject reached universal dimensions, linked to the collapse of military dictatorships in Latin America, the dissolution of apartheid regimes in South Africa, and the disintegration of the Eastern Bloc.

Today, the historical dimensions of collective memory, its reflections on daily life, and its increasing universality in the pursuit of social peace are frequently brought to the agenda with its moral and conscientious dimensions. Concepts such as "culture of remembering," "truth," and "social peace," which are becoming increasingly universal with their moral and conscientious dimensions, highlight the need to discuss the political, social, and historical background of the memory.

Dealing with the past is not just an academic question; an increasing number of recognitions and experiences in several countries, along with international acceptance at a global level and studies conducted at the United Nations, have brought this issue to the fore as one of the most pressing challenges of today’s politics.

Looking at different countries’ experiences in facing the past indicates that the primary goal was not to start a process just to punish crimes committed in the past, but rather to repair the sufferings of victims and achieve social healing. So, efforts to understand the mentality of victims and survivors who suffered in the past, and to develop an approach that takes their emotions into consideration would be helpful to reach the goal.

In this short piece, facing the past is briefly summarized from the perspective of cultural and identity groups.

Facing the past and identities

Worth to note, in discussing issues of identities, “facing the past” has a special place as a living and dynamic process effective in the formation of identities. So, a close relationship between identity formation and cultural development in the past needs to be underlined. In other words, the course of remembering the past helps the revival of memories of cultural identities and contributes to building identity.

In the course of processes of facing the past, efforts also need to be designed to repair the injustices through punishing the perpetrators of crimes and inventing some means to compensate for the losses of victims, including moral satisfaction. Also, questioning the political system, structures, and mentality that caused the crimes and violations of rights needs to be studied to be able to design the proper programs and to draft the necessary acts.

In particular, facing the past traumatic events in nation-states is becoming a new issue raised by denied minorities, and these demands are supported by international conventions and institutions as it has developed as a concept with its socio-political and ethical perspectives. Current observations show that the importance of the past on the present social order is becoming increasingly effective, and recent developments are enforcing almost all societies and nation-states to deal with it.

On the other hand, historical experience has proved that effective policies in facing the past can only be achieved in a constitutional democratic system recognizing multiculturalism. In the absence of such a democratic system and in case of ignoring facing the past, it may lead to social unrest and instability of the system.

Since facing the past of traumatic histories offers a means to promote dialogue between conflicting groups, the primary aim is expected to be, at least partially, to restore the victims' sense of justice and the dignity that has been injured over the years. To reach such a goal necessitates a broader approach to introduce an understanding of the rights of others and respect for identities. It is also accepted that facing the past processes would be helpful to build a society recovered from old injustices that denied the existence or rights of the others. Would be right to mention, fruitful discussions on social peace and reconciliation, as well as the language of peace and the law of peace, can be achieved through these dialogue processes.

The fact that the culture of remembering and programs for facing the past are no longer considered specific to a particular region, and that observations made with an outcome-led approach show that processes in different societies across various geographies concluded with more or less similar outcomes. So, by having these experiences, it wouldn’t be wrong to talk about certain policies and programs to apply to reach the goal.

Within the lessons learned from common features, when considering each case, the ‘reparative’ approach, which takes into account local culture and traditions, appears as the most effective method in resolving the past injustices for unrecognized identities. Briefly, this approach offers a democratic dialogue between the state and the “others,” “cultural and identity groups,” to develop a culture of peace and reconciliation through dialogue to recognize and address the past sufferings and injustices.

And, in building a peaceful future for a multicultural society with internal conflicts, recognition and acceptance of the legacy and painful memories of the past is crucial. In particular, it is important to remember that the experiences of oppressed identity groups are vital in building their future, and special care must be taken with the language and terminology used toward these identity groups.

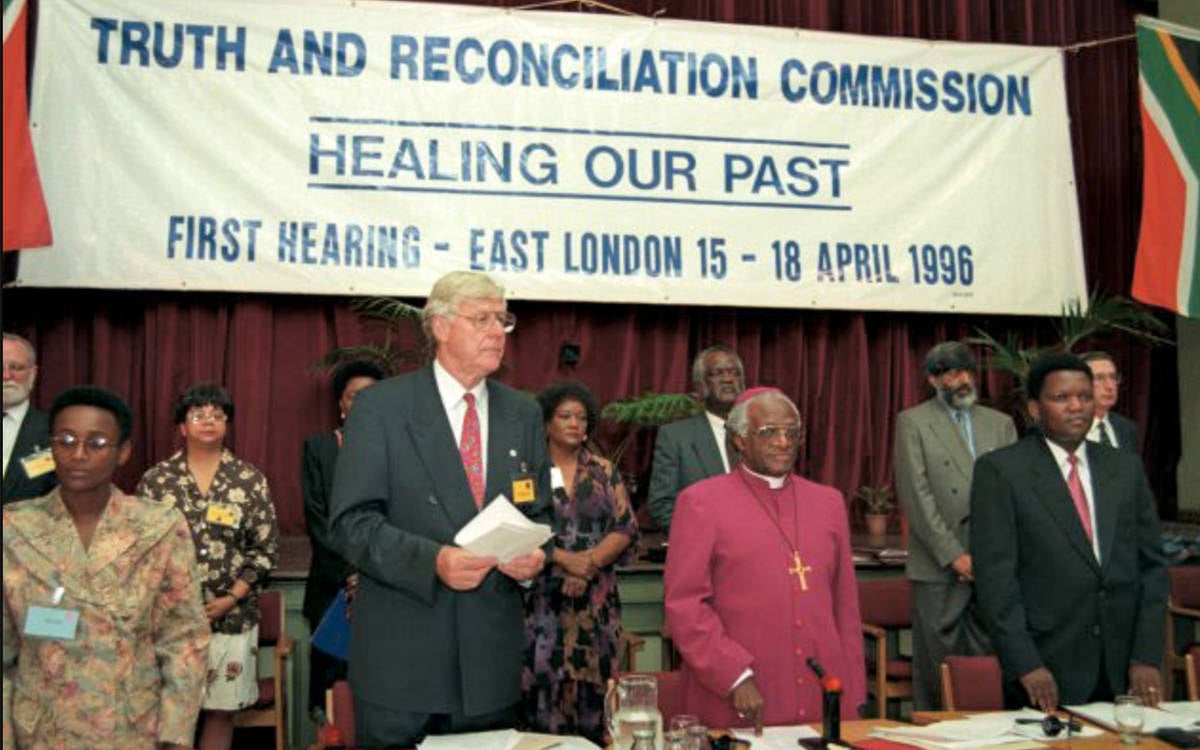

Truth commissions, which should be briefly mentioned within this context, are also important. Conflicts, serious human rights violations, and traumas are addressed within the framework of restorative justice practices, as part of peacebuilding efforts that have been established and tested under various names in more than 40 countries to date. Due to their internationally recognized success, the United Nations also assists member states in this field through its comprehensive works.

Looking at samples around the world, it is seen that truth commissions mostly emerge as a result of changes in power, and are brought to the agenda by the initiatives of victims and civil society, and in many cases, can be established as grassroots movements seeking justice, even against the state.

Our past calls for facing the past

Looking at our country, we see severe traumas and sufferings stemming from its historical experiences and events, where nationalist-racist political preferences maintained a political system that prevented the culture of coexistence of differences. In other words, the dominance of a strong centralist and nationalist tradition, strengthened with military coups and internal conflicts, has not allowed the development of a political climate to bring this issue to the agenda.

As a society that has experienced severe conflicts and massacres in the past and carries traumas in its memory, addressing the issue on different platforms is of great importance for reducing social tensions, healing, establishing peace, and for transitioning to a democratic peace process. Due to the nationalist political climate and discourse, the dissemination of discussions on this issue to broad segments of society, and the rise of a strong social demand to deal with the past have been obstructed.

Experiences of facing the past since World War II, particularly in Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Japan, and Latin America in general, offer very useful lessons for our country. Furthermore, it is evident that the policies of forgetting and suppression that have dominated Turkey's relationship with the past have not yielded the intended results. Considering these experiences, it should not be seen as an exaggeration to state that a culture of remembrance and facing the past is crucial for developing social peace, democratization, and a culture of coexistence.

On the other hand, countless unsolved murders, extrajudicial killings, disappearances in custody, and enforced disappearances have occurred, mostly in the 1990s, perpetrated by official and semi-official paramilitary forces of the state. The fate of thousands of disappeared people remains unknown, and even their burial places are unknown; relatives of the disappeared have been striving for years to uncover the fate of their loved ones, continuing their legal efforts. Therefore, fair and effective legal investigations and punishment of perpetrators would play a crucial role in healing the traumas and grievances of the past, and would make a significant contribution to social peace.

Briefly, investigating the crimes in which the state participated, punishing the perpetrators, and addressing the suffering, repairing all material and moral damages resulting from these crimes constitute an important part of the process of facing the past.

(This piece is primarily based on Prof. Dr. Mithat Sancar's book, "Geçmişle Hesaplaşma”, published by İletişim Yayınları, in 2010 )

(NT/VK)