An antidote is a biological or chemical substance that neutralizes or counteracts the effects of a poisonous agent. This concept can also be used metaphorically in political and social contexts. The “poison” of the nation-state lies in the centralized, monolithic, homogenizing, and exclusionary nature of modernity. The effects of this poison are most clearly seen in the suppression of plural identities through the principle of “one language, one flag, one nation.” The Republic of Turkey is one of the most typical examples of this formation.¹

By centralizing decision-making processes, the nation-state excludes local self-governance mechanisms. Instrumentalizing violence and militarism, it is highly effective in producing internal and external enemies, turning itself into a graveyard of peoples and beliefs.² Due to its patriarchal character, it marginalizes women and LGBTQ+ individuals from social and political life and deepens alienation from nature through its developmentalist, industrialist approach.³

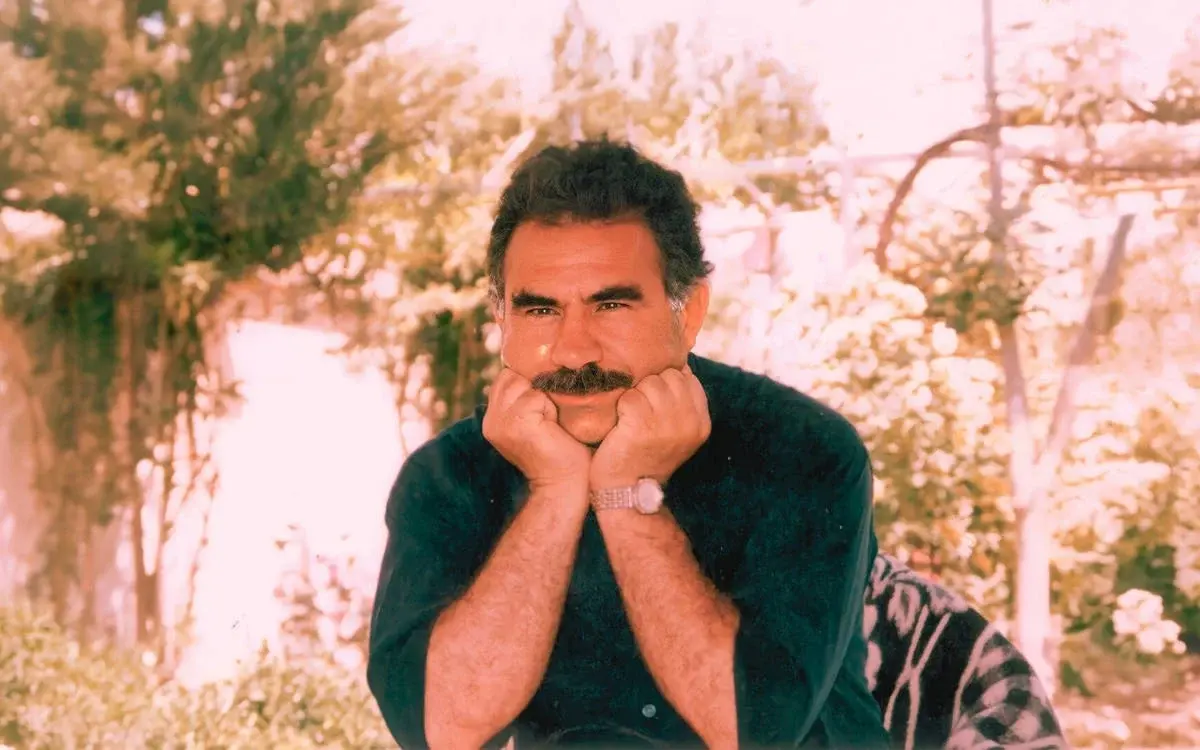

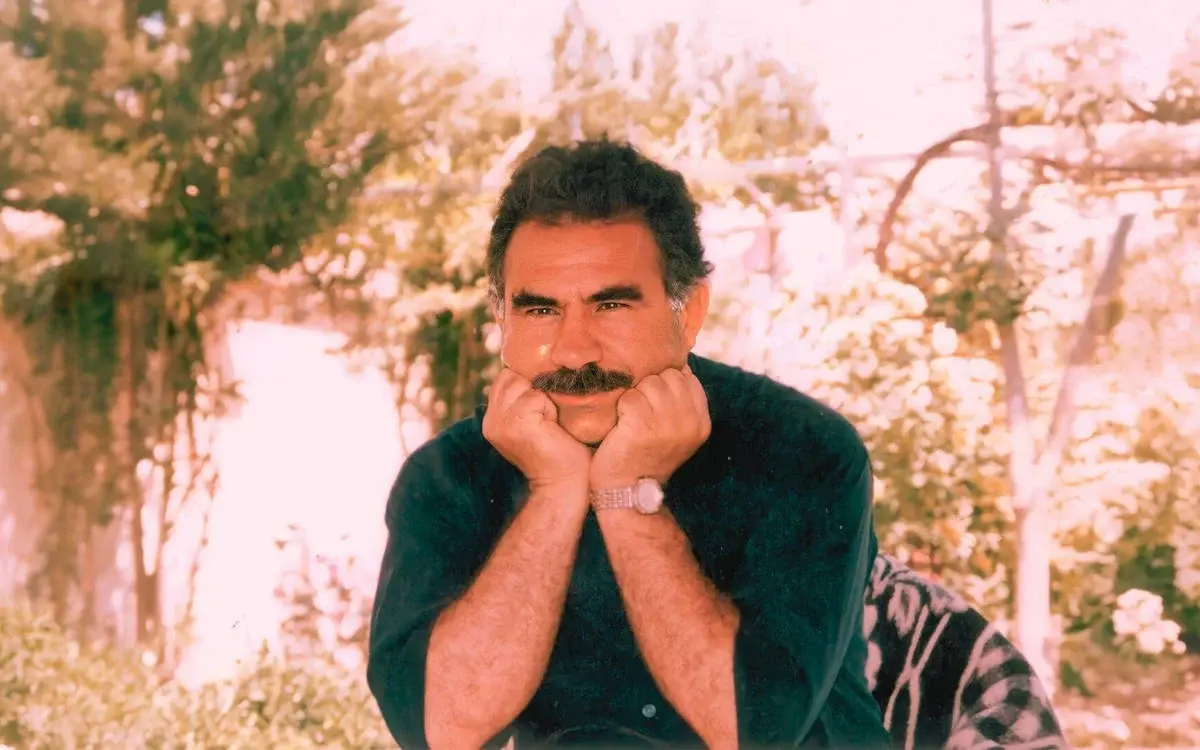

In this context, the concept of the “democratic nation” developed by Abdullah Öcalan is proposed as an antidote to this poison. Öcalan offers a comprehensive historical and theoretical critique of capitalist modernity and sees alienation from nature, society, and the individual as core crisis areas of the system.⁴ As an alternative paradigm to the nation-state—the political form of capitalist modernity—he proposes “democratic modernity,” placing the idea of the democratic nation at its core.

Theoretical foundations and intellectual kinships

Although the concept of the democratic nation was systematically developed by Abdullah Öcalan, fragments of the idea can be found historically in the works of various thinkers. In his 1882 lecture “What Is a Nation?” at Sorbonne University, Ernest Renan defines the nation not through ethnicity or language, but through shared historical memory and the will to live together.⁵ This approach parallels Öcalan’s stance against ethnic reductionism.

Collectivist anarchist thinkers such as Mikhail Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon defended decentralized, self-governing federations of peoples in opposition to centralization.⁶ They viewed the nation not as an ethnic entity but as a political and solidaristic formation—an understanding that shares theoretical kinship with Öcalan’s concept of democratic confederalism.

Murray Bookchin’s theory of “libertarian municipalism,” based on direct democracy and popular assemblies, finds practical resonance in Öcalan’s proposals.⁷ Meanwhile, the Zapatista movement in Mexico presents a model based on local democratic self-governance against the central state; Öcalan advances this model further by elevating the democratic nation to a theoretical conceptual level.⁸

Fundamental principles of the democratic nation

According to Öcalan, the democratic nation first and foremost acknowledges ethnic, religious, cultural, and gender pluralism. He does not equate the nation with the state; instead, he sees the nation as a form of social organization and solidarity. Through local assemblies, communes, and women-led structures, he promotes grassroots democracy. Arguing that “insistence on socialism is insistence on being human,” Öcalan places women’s liberation as a foundational principle and embraces ecological living as a response to capitalist modernity’s antagonism toward nature.

“The democratic nation is not a form of state,” Öcalan says, “but a social union formed through the free and equal organization of peoples, ethnicities, religious communities, women, and similar groups within a democratic society.” This perspective is not merely a theoretical doctrine but has begun to materialize as a lived reality in Rojava.

Experiential testimony: The Internationalist Academy as democratic nation practice

For two days, I joined a commune of internationalist youth from various nations (Catalan, Basque, French, English, Italian, Argentinian, Polish, etc.) to give a seminar titled “Social Ecology on the Axis of Democratic Modernity.” The daily language was Kurdish, and many participants had begun learning it within a few months. The educational sessions were held in Kurdish, English, and French.

The collectivism I witnessed in those two days, the detailed planning of everyday life, and the shared practices of daily routines took me back to the early days of the PKK—before it was even an organization or a party, to a time when its members were simply known as “students.” The experiences of Kemal Pir in Ankara’s Tuzluçayır neighborhood before the PKK formally existed are recounted by longtime activist Rıza Altun, who said: “Kemal Pir arrived, and Tuzluçayır became Apocu.”⁹

During sessions on capitalist modernity, industrialism, direct democracy, communes, and confederalism, we discussed the theory of the democratic nation. When asked, “What do you think about the democratic nation?” I gave an answer that made the concept tangible for me: “The democratic nation is the action and practice we create together—you, you, you, me, and all of us.”

According to academician Nazan Üstündağ, the PKK resists not only the political domination of the state but also the monopoly of knowledge and education. She argues that the PKK has created a counter-academic space, an alternative field of knowledge production.¹⁰ Women’s education is at the heart of this structure, encompassing not just literacy but also the reconstruction of emotions, relationships, and ways of living.

This pedagogical approach reveals the epistemological and ontological transformative potential of the democratic nation. For me, the experience was proof that this theory is not just an abstract proposal, but a livable model. Resistance gains meaning not only through opposition but by offering a transformative and viable alternative. The democratic nation is the path toward building that alternative. (EJA/VK)

Footnotes

- For a critical historical analysis of the Turkish Republic's nation-building process, see: Tanıl Bora, Milliyetçiliğin Kara Baharı, Birikim Yayınları, 2011.

- On the militarist structure of the nation-state and its exclusionary nature, refer to: Cynthia Weber, International Relations Theory: A Critical Introduction, Routledge, 2014.

- For a feminist and ecological critique of the nation-state, see: Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Autonomedia, 2004; and Maria Mies & Vandana Shiva, Ecofeminism, Zed Books, 1993.

- Abdullah Öcalan, Manifesto for a Democratic Civilization, Vol. I: Civilization – The Age of Masked Gods and Disguised Kings, International Initiative Edition, 2015.

- Ernest Renan, What is a Nation?, Lecture at the Sorbonne, 1882. Translated by Ethan Rundell, available at the Collège de France archives.

- Mikhail Bakunin, Statism and Anarchy, Cambridge University Press, 1990; Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, The Principle of Federation, 1863.

- Murray Bookchin, The Next Revolution: Popular Assemblies and the Promise of Direct Democracy, Verso Books, 2015.

- Subcomandante Marcos & the Zapatistas, Our Word is Our Weapon, Seven Stories Press, 2001.

- Rıza Altun’s accounts are documented in interviews and historical texts about the early years of the PKK. See also: PKK: Kürdistan’da Halk Gerçeği ve Özgürlük, Mezopotamya Yayınları, 1991.

- Nazan Üstündağ, The Politics of Women's Freedom in Kurdish Movement, Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2016.