Aadel Essaadni is a relaxed, well-built man. He has a witty sense of humour when you least expect it, which often follows with endless laughter, making him a real character. Although he is very discreet in nature, you will bump into him at every cultural event in Casablanca. He is one of a few key indispensable key players creating a new role for culture in city life.

Aadel Essaadni is a relaxed, well-built man. He has a witty sense of humour when you least expect it, which often follows with endless laughter, making him a real character. Although he is very discreet in nature, you will bump into him at every cultural event in Casablanca. He is one of a few key indispensable key players creating a new role for culture in city life.

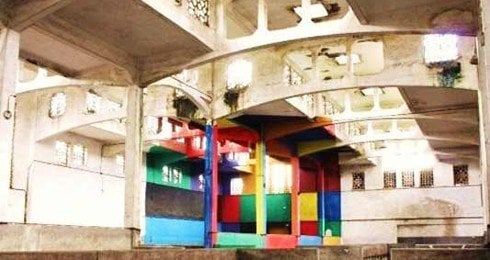

He takes on his duties without ever getting tired. He earns his living by managing the Institute of performing Arts in Casablanca, which he founded in 2007. This centre offers professionals ongoing training in technical and administrative aspects of show business. He is a technician in scenography and he gives architects advice on sound and light installation in show business. This year he was the general coordinator for the jazz festival at Challah in Rabat. Since 2004 he campaigned for Casamémoire, an association working to protect 20th century heritage in Morocco. He is the technical director of the cultural centre of old slaughterhouses in Casablanca, managed by a number of associations represented by Casamémoire. He is also committed to Arterial Network, an association based in South Africa campaigning for the rights and status if artists', recognising culture as a human right, consolidating a creative economy and developing exchanges with Southern countries in the cultural field. Moreover, at the moment he is trying to enhance Arterial Network's national status in Morrocco. He smiles whilst saying "If I have energy, it's thanks to my unconsciousness! I describe myself as a kamikaze of culture."

Many responsibilities at hand...

Aadel Essaadani was born in Casablanca in 1967. He still has vivid memories of the centre of the city, the area he was raised in: "there was a municipal library; the municipal Theatre of Casablanca was still in place, with a schedule ..." At seventeen he got his A' levels and he left to pursue his studies in France and "expand his horizons". "At the beginning, I studied Science just like everybody else", he says ironically. He then studied City planning and applied to pursue his thesis studies in Urban Sociology. "Whilst working on the notions of citizen dwelling and citizen status in public spaces in Casablanca, I became interested in theatre and completed a training programme in stage management". For twenty years, he worked as Communications and Technical director for festivals in France, where he directed the summertime festival of Perpignan. By that time he was already participating in protest campaigns. In fact in 2003, through the CGT spectacle, he participated in the workers protest in the entertainment industry. "I was with them when it was decided to cancel the festivals of Avignon and Aix en Provence". In 2004, he became a cultural entrepreneur. For three consecutive years, he was in charge of a jazz club in Perpignan called l'Ubu: every night a new concert was held and an exhibition was opened every two weeks in the Arab and gypsy quarters. He appreciated the artistic experience and enjoyed the cultural mix.

On his arrival back to Casablanca in 2008 his love for Jazz led him to manage this genre of music again in a place called le Rocher. Le Rocher, a vacated place located next to a lighthouse, underneath a trendy advertisement, where the loud commercial music bewilders. On the ground floor, a cosy hall plays live music. "I love Jazz music. I do what I do because I enjoy it and to bring to life a real Jazz club once again". Aadel Essaadani is nostalgic: "Casablanca was once surrounded with music: Don Quichotte, Titan , Réserve, Siemens, Negresco ..... I discovered Jazz in the area I lived in. At a young age, once, my father sat me on a piano bench and I emptied a glass of strawberry milk on the pianist. Jazz was part of our daily life. Our daily spots were not mosques but garages, banks and nightclubs". For a whole year, different people came by. Jazz at Le Rocher gathered "old nostalgic jazz lovers who discovered Jazz whilst studying abroad and young people at the brink of a new discovery. The young were very receptive since there are very few places in Casablanca where you can hear live improvised jam sessions". However this did not go on for long. "There is not enough happening here. We had to get artists from overseas. " This implied paying their trip, accommodation and short stay. "Expenditure is twice more than that in Paris or Brussels, where you find an entrance fee for such places, something unheard of here because the public is not used to it." Regretfully, Aadel Essaadani says that "the public does not like to mix here. If the young generation is present, then the older generation with purchasing power is omnipresent". The fact that only one type of musical genre is being played is sometimes badly perceived: "They have suggested that I should play a bit of chaabi!"

... a struggle

As an observer, he learns from his own experience and has a clear picture of the cultural situation in Morocco. In fact, he has numerous propositions for a substantial cultural program, something he vehemently preaches in practice.

Aaadel Essaadani insists that the importance of change in the cultural field should be based on three aspects: the artistic, administrative and technical aspects. Training in all three aspects is still non-existent. From an artist's point of view, « everyone is self-taught here ». What about Music Academies? "Only private ones exist. Even the working class can not afford to send their children there, especially since they are already paying private school fees .....So this makes culture a luxury when it is a right". Since art education is totally absent in schools, "this is resulting in a less number of artists and just a public. A public without the necessary knowledge ..." Now regarding technical aspects in the field of cinema, Aadel Essaadani remarks a slight improvement. Unfortunately, in live concerts such as the festivals of Casablanca and that of Mawazine, all technicians are French and they are not necessarily good. On the other hand, if we train our people, this could also be an opportunity for work too!" Moreover you can not train people "to realise projects and become the backbone of a good cultural administration". Consequently, "We do not have the necessary economic support to enable artists to do well internationally and to boast of their country".

The absence of true cultural policy saddens Aadel: " Nothing is really changing although we often hear that we are one of the most advanced countries in the African continent, next in line after South Africa ..." He objects the fact that culture is not seen an economical force: " The state should realise that culture could increase tourist numbers". What about artists' rights? "Artists only have a permit and a medical insurance that is practically it. There have been no reforms yet within the Moroccan Copyright office. Due to the lack of such a reform, artists still do not bear the fruit of their work and can not make a living out of their work: "Those who sustain Moroccan culture do not reap benefits and they are still perceived as gypsies". Aadel Essaadani speaks against the present policy and points his finger to festivals: "We organise big festivals to distract people from realising that we do not do anything" : no support mechanisms for creativity, no awareness of sociological art and no measures in place to make up for a lack of public culture centres. "There are only nine cultural centres in Casablanca", for a city inhabited by more than 4 million people. Aadel sustains that "the majority do not know how to manage these centres. Those nominated do not necessarily have the right qualifications. To do this job one has to dispose of a particular sensitivity and an artistic direction, in the interest of the public and ready to manage activities in the best way possible. Without good management these centres can not be beneficial". He appeals for more leasehold measures, a system devised by the government to entrust these community centres to associations needing these centres to function properly: "They would first supply a scope statement, followed by a convention and an evaluation". He says that this practice is already in place for sport and the service sector but those responsible are lacking to extend it to the culture sector. Till today we have only seen two initiatives: the 20 year lease of the Kasba des Gnaoua à Salé to the Qarasina Company, a company teaching circus performing arts to young children and the second initiative was that pertaining to the slaughterhouses of Casablanca. Moreover, "it is taking ages to sign the second convention. We asked for five to six years, but originally we were supposed to get a convention of 90 years!" Aadel Essaadani regretfully says that "the Boulevard of Jeunes Musiciens had to look for a private place" and embrace some common practices: "They make you believe that you have to be kind to get access to a public centres when it is actually our right to have access to community centres!" They sigh: "If only we had an intelligent mayor in Casablanca, we would have real change!"

Aadel Essaadani is not giving up and has new projects in mind: the renovation of the cinema 'L'Empire' in avenue Mohammed V, in the city centre. An architectural master piece, signed for in 1927 by Aldo Manassi, "the glory days of cinema in Casablanca!" he says enthusiastically. Aadel is trying to get an authorisation for a transformation of this cinema from the three remaining heirs from the original 18. He is planning to open a jazz club and a bar with contemporary music. "This would solve the problems of cinema theatres closing down and performing arts without a place". So, why not copy Parisian venues such as Bobino, la Cigale, l'Olympia, originally cinemas converted into venues for shows? "In Casablanca, we do not have a venue like le Zénith which can host 5000 standing people. Moreover the era of transforming cinemas in shopping centres is over". Taking delight in what he does and loyal to his beliefs, Aadel without any hesitation says "I want to sell beer to produce music and not the other way round. I do what I do to feel proud of my country and to bring out its potential. Moreover, if all of this works, this will be the beginning of a new movement and I would be the happiest of men".(ÇT)

---

www.arterialnetwork.org

www.artsinafrica.com

www.linstitut.org