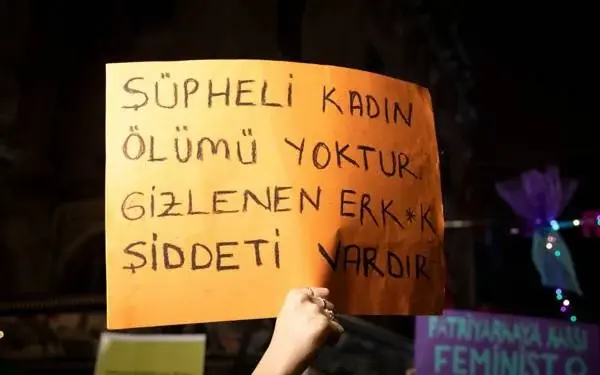

Strangulation acts are one of the forms of violence that often remain invisible in cases of male violence, yet pose a serious threat to life.

The lack of visible injury leads to these acts being considered as “simple assault” during investigation and prosecution processes, resulting in impunity.

However, international research shows that non-lethal strangulation acts cause severe physical and psychological consequences and are even strong indicators of a high risk of femicide.

Prof. Dr. Kadriye Bakırcı, in her study on non-lethal strangulation acts which have been defined as a specific offense in England and Wales, discusses why this form of violence should be legally recognized.

We spoke with Bakırcı about the relationship between strangulation acts and male violence, their normalization in the context of sexual intercourse, the inadequacies of current legislation, and potential steps that can be taken in Turkey in this field.

In your article titled “Non-lethal Strangulation Acts as a New and Specific Type of Domestic Violence and Crime: The Example of England and Wales,” published in İktisat ve Toplum Dergisi on Jan 21, 2026, you mention that bianet’s 2024 male violence data was a source of inspiration for writing this article. Could you share with us the reason for this?

In 2024, while I was writing my article titled “Violence Against Women and Girls in Edirne: Can It Be Written Without Scientific Data?” for bianet, I noticed in the data compiled by bianet that two of the women subjected to domestic violence emphasized acts of “throat grabbing.”

Perhaps because I had never come across this act in the studies I had read before or in national and international regulations and literature, I became curious about how widespread it actually was.

Once I started researching, I realized that these acts, which have very severe consequences, are in fact extremely common and have been defined as a specific offense particularly in Anglo-Saxon law. Upon this realization, I decided to write on the subject.

bianet is Monitoring Male Violence

So why did you write this article?

My aim, as with all the work I have done for over 30 years, is to raise awareness on this issue in Turkey, to ensure that researchers from different disciplines also study this topic, to include related questions in field research on violence in general and domestic violence in particular, to collect data, and of course, to ensure that it is regulated both in Turkish legislation and in international legislation.

Why did you mention the example of England and Wales?

Non-lethal strangulation acts were defined as a specific offense in England and Wales in June 2022.

In the literature, strangulation and suffocation, and the acts that fall under these categories, are defined differently depending on the discipline. Similarly, in countries that regulate this issue, there can be differences in definitions and approaches. Therefore, in order to introduce the subject to Turkey, I initially chose to take the regulations in England and Wales as an example. Once the topic is introduced, if other researchers are curious, they will look into the legislation of other countries as well.

Can you summarize the definition made in the legislation of England and Wales?

The acts banned as a specific offense in the England and Wales region are acts of applying pressure to the neck area and cutting off breathing or the ability to breathe. However, since not all of the English terms have Turkish equivalents, I examined these acts under the general heading of “strangulation acts” in my article for practical reasons.

In this context, strangulation acts are violent acts that can result in loss of consciousness, permanent damage, or death due to the deprivation of oxygen in the body caused by external physical actions such as cutting off a person’s breathing or applying pressure to the neck.

Non-lethal strangulation acts, in light of current England and Wales regulations, can be defined as strangulation acts that do not cause the death of the person subjected to them and do not necessarily cause visible injury, or acts during sexual intercourse referred to as “rough sex” that may be consensual as long as they do not cause serious harm, but where the defense of consent is not accepted in cases where serious harm occurs.

Are strangulation acts also occur during sexual intercourse?

Unfortunately, yes. I too was horrified to learn this during my research. Studies have shown that more than one-third of women under the age of 40 in the United Kingdom have been subjected to unwanted acts such as slapping, strangulation, mouth covering, or spitting during consensual sexual intercourse. In a survey conducted with men to understand how “rough sex” is experienced, 71% of male respondents stated that they slapped their partners, grabbed their throats, covered their mouths, or spat on them during consensual “rough sex.”

You said that strangulation acts are very common and have severe consequences. What kind of severe consequences are there?

Research shows that even if the act does not result in death or immediate death, non-lethal strangulation acts alone can lead to brain damage, organ failure, long-term physical and mental health problems, and increase the risk of paralysis and neurological disorders. Secondly, non-lethal strangulation acts are considered indicators of femicide risk.

One study revealed that most of the victims were later killed by the perpetrators of the strangulation acts (mostly former partners). A third serious consequence that is emphasized is the increased risk of suicide among victims.

Are strangulation acts only banned in the context of domestic violence?

No. This offense is not limited to domestic violence, it covers all incidents involving non-lethal strangulation acts. In addition, if the offense is committed with a racist or religious motive, it constitutes an aggravated form of the crime.

Do current legal regulations not cover these acts, such that new regulations were needed?

Non-lethal strangulation acts often do not emerge immediately or do not result in visible injury.

Data from the United Kingdom shows that when non-lethal strangulation acts do not cause visible injury, they are not effectively investigated or prosecuted. Therefore, a result leading to impunity has emerged.

Furthermore, the previous legal approach did not encompass the risk posed by non-lethal strangulation acts or the protective measures that should be taken before a murder occurs. In addition, the old legislation did not impose a limitation on the consent defense regarding strangulation acts during sexual intercourse.

Do the new regulations meet all the demands in this field?

Unfortunately, no. The new legislation also has shortcomings, but it is often not possible to create a perfect legal regulation. What is important is the recognition of emerging shortcomings over time and the effort to correct them.

What would the definition of non-lethal strangulation acts as a specific offense change in Turkey, in terms of both criminal law and the protection of women?

The creation of a specific offense of non-lethal strangulation would significantly strengthen the existing legal framework on domestic violence and address a major shortcoming in traditional legislation.

If a specific offense is defined, it would be recognized that non-lethal acts of applying pressure to the neck and cutting off breathing are not “simple assault,” that they differ from general injury acts, that the acts are highly dangerous in themselves, that visible injury is not required for the offense to occur, that in cases of serious harm risk during sexual intercourse, consent cannot be accepted, that the acts carry a risk of repetition and can be indicators of femicide, and that they constitute one of the types of coercive control crimes.

Such a regulation would address fundamental shortcomings such as strengthening protection for victims of domestic violence, improving risk assessment processes in domestic violence cases, contributing to the prevention of lethal violence through the early identification of high-risk perpetrators, preventing law enforcement and courts from downplaying the violence, enabling more appropriate and proportionate penalties, increasing the confidence of victims in reporting incidents, and aligning domestic law with international developments and best national practices.

With the recognition that violence carried out through strangulation acts inherently carries a life-threatening danger regardless of visible injury, the law would finally align with the lived experiences of victims.

The use of specific offense definitions and codes for non-lethal strangulation acts would allow for healthier data collection on violence, more consistent sentencing practices, and the fulfillment of the need for more effective risk assessment.

How can academia, bar associations, and women's organizations carry out joint work in this area?

Law is no longer as static as it used to be. It is constantly undergoing change and transformation. In Western legal systems, governments no longer regulate top-down. For instance, in the area of violence against women, they shape the law based on the demands of victims and their families.

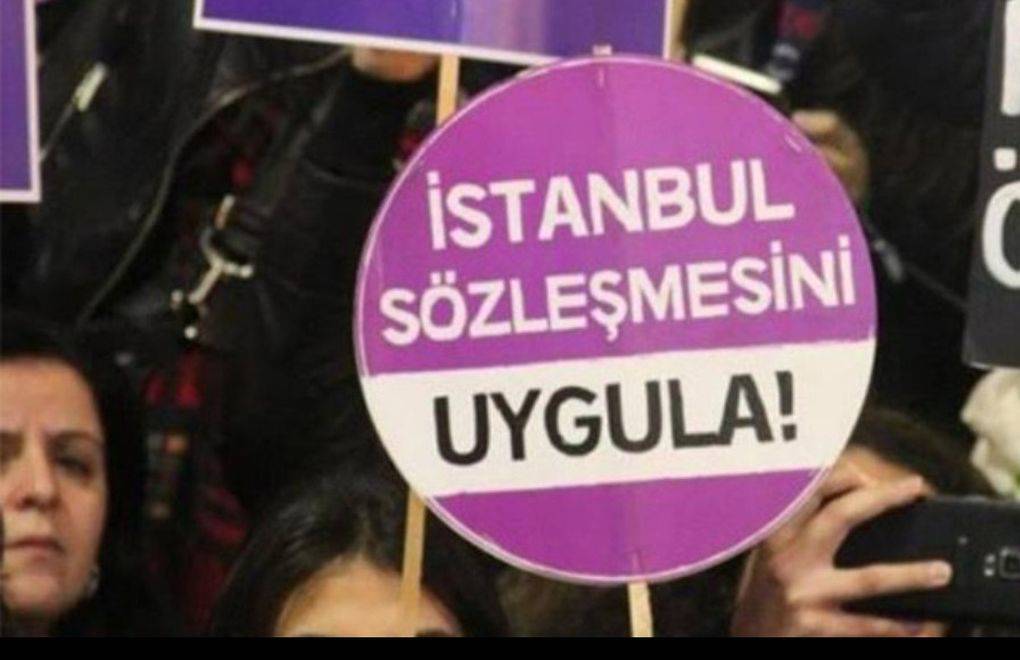

Therefore, academia, bar associations, and women’s organizations can jointly strive to ensure that Turkey aligns with the changes taking place on the international stage.

Do you think legal recognition of strangulation acts could be a “threshold” in the fight against male violence in Turkey?

Between 2000 and 2011, when the process of harmonizing with European Union law was prioritized, Turkey in fact passed many thresholds. Major reforms were made in Turkish law.

Therefore, we are now in a post-threshold period. The inclusion of “coercive control offenses” and “non-lethal strangulation acts,” about which I wrote articles in 2021 to introduce them to Turkey, would not constitute a threshold, but would reinforce and stabilize the threshold that had already been crossed with previously adopted laws. (EMK/VK)