In her book Discipline of Death (2018), Prof. Dr. Zeynep Sayın analyzes the state’s approach to the dead and practices surrounding death, revealing how the violence of power operates through death and mourning processes. The book particularly focuses on funerals, forms of commemoration, and the right to mourn. Sayın argues that control over the dead body is, in fact, a reflection of the power that seeks to be established over the living.

According to Sayın, the state does not allow mourning for certain dead because such mourning keeps social memory alive. Preventing the right to mourn and rendering the dead invisible is not only a suppression of emotion by the state but also a suppression of resistance and remembrance.

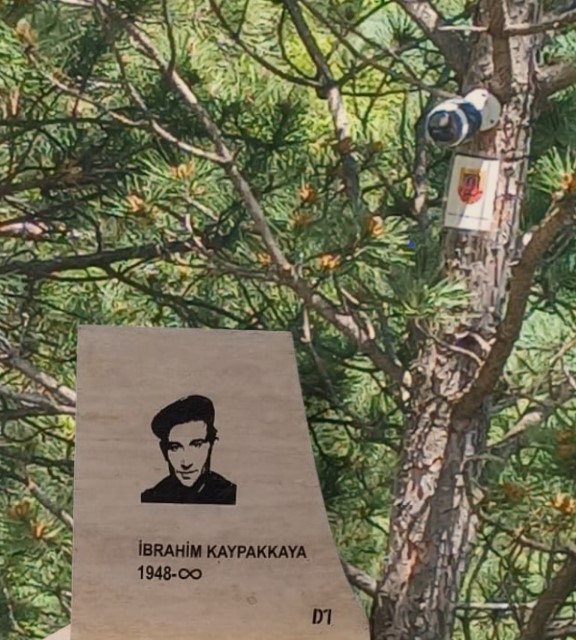

On May 25, the newspaper Özgür Gelecek published a report titled “24/7 camera surveillance at Kaypakkaya’s grave!” According to the report, ID checks, drone surveillance, and police control have become routine at commemorations held at the grave of İbrahim Kaypakkaya. However, the increased blockade on the anniversary of Kaypakkaya’s death “has reached a new level this year.” A camera placed directly in front of the gravestone now records visitors.

İbrahim Kaypakkaya was a Turkish communist revolutionary and Marxist-Leninist theorist who founded the Communist Party of Turkey/Marxist-Leninist (TKP/ML) in 1972. Known for his radical opposition to imperialism and feudalism, he advocated for armed struggle to achieve a socialist revolution in Turkey. Kaypakkaya was captured and tortured by Turkish authorities in 1973, dying under brutal conditions

Commenting on the installation of a security camera at Kaypakkaya’s grave, Zeynep Sayın said, “In 1848, a specter was said to be haunting Europe. They are afraid of ghosts. And of visitors. A grave is a place of visitation. It contains a saint, an ancestor, an elder.”

“Both unlawful and aimed at deterrence”

Evaluating the legal dimension of the development for bianet, lawyer Meral Hanbayat said:

“We have always experienced the confiscation or damage of gravestones belonging to revolutionaries, the blockade or prevention of cemetery commemorations, and legal proceedings for ‘praising crime and criminals’ or ‘engaging in propaganda for an illegal organization’ during such events. A police station was built very close to İbrahim Kaypakkaya’s grave. Visitors are subjected to ID checks, their images are recorded, and ultimately they are profiled... These have been ongoing practices for years. But placing a camera at his grave is unacceptable. It is a natural part of life for people to commemorate their loved ones and those they value at their graves, and to criminalize this is both unlawful and a means of deterrence.

“Every commemoration of Kaypakkaya has been recorded for years. Since the early 2000s, making any statement, sharing photos, or issuing press releases about Kaypakkaya has become subject to investigation. These investigations are not limited to cemetery commemorations. Tweeting about Kaypakkaya is similarly punished. Almost every word said about Kaypakkaya becomes a subject of criminal investigation.

“A special blockade for Kaypakkaya”

“Yet there are many acquittal decisions stating that this is not a crime and should be evaluated under freedom of expression. Referring to decisions by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Constitutional Court (AYM) on freedom of expression, there are many rulings regarding both the commemorations held at his grave in Çorum and those held nationwide. Despite these rulings, Kaypakkaya commemorations continue to be met with profiling, detention, arrest, and dismissal from public service.

“For instance, on May Day 2024, dozens of people who hadn’t even entered the rally area but were carrying posters of Kaypakkaya were arrested for ‘propaganda for an organization.’ These individuals were later acquitted. Similarly, in cases filed for ‘praising crime and criminals,’ acquittals were issued. But in recent years, people have been barred from entering permitted rallies solely because they carried Kaypakkaya posters. The police pressure the organizing committees not to allow these people into the area.

“It is clear that a special blockade is applied to İbrahim Kaypakkaya. This is directly related to the state’s perception. Kaypakkaya’s political analyses and methods of struggle are seen as more ‘dangerous’ by the state. The stance of the state, the judiciary, and the police becomes incredibly harsh when it comes to Kaypakkaya.”

Pınar Aydınlar ruling

Folk musician Pınar Aydınlar was acquitted in 2023 in a case where she was tried for songs she performed and for commemorating İbrahim Kaypakkaya at the 10th Munzur Culture and Nature Festival held in Dersim in 2010.

Accused of “propaganda for an organization,” Aydınlar attended the hearing at Tunceli 2nd High Criminal Court via SEGBİS (video link), and after 13 years, was found not guilty. Commenting on her trial, Aydınlar said, “Performing works written in memory of revolutionaries who struggled for the people is fundamental for revolutionary artists.”

The funerals of Basavaraju and 26 Maoists

Another development regarding control over the dead occurred in India. On May 21, in the Chhattisgarh state, Nambala Keshav Rao (Basavaraju), General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), and 26 Maoists were killed in a clash with security forces. The Indian government described this massacre as the most significant anti-Naxalite (Marxist-Leninist-Maoist movement) operation in recent years. The bodies of the Maoists were displayed lying on the ground with their faces exposed and shared with the media.

According to Hindustan Times, Basavaraju’s body was cremated under official supervision in the Narayanpur region, as no relatives claimed it. Police stated that the burial process was carried out with legal permits and administrative oversight, and that no application was made by Basavaraju’s family to retrieve the body.

However, Basavaraju’s mother Bharatamma Rao, and his brother Sajja Srinivasa Rao had submitted two separate petitions requesting the return of his body. Following this development, Basavaraju’s brother said the Chhattisgarh police were lying, violating human rights by not complying with Supreme Court rulings, and not allowing the bodies of the deceased Maoists to be transported to their hometown:

“We wanted to bring the bodies to our hometown. They might have started to decompose, but we still wanted to send them off on their final journey at home. The police did not allow it.”

The theory of haunting

In his 1993 book Specters of Marx, French philosopher and literary critic Jacques Derrida developed the theory of haunting, which has been further explored in a sociological context by thinkers like Avery F. Gordon. This theory asserts that the suppressed or excluded past continues to haunt the present like a ghost, returning to shape the present. Hauntology suggests that ghosts are not confined to memories but also move within social structures.

Tools and methods such as cameras, profiling, blockades, and refusing to return bodies to their relatives are among the strategies states use to cope with political specters. The effort of states to control funerals is essentially their own “burial” ritual. Through these acts, states attempt to bury the past, to render it invisible.

But hauntology also tells us this: every repression can cause the specter to return even more powerfully. Because what haunts is not only the presence of these figures, but also their lives, the violence they endured, and the quest for justice by their families. Therefore, the haunting has this function as well: it breaks the state’s domination over memory and keeps alive the families’ and relatives’ demands for justice and remembrance.

(TY/DT)