Samandağ is a city situated at the point where the Musa Mountain, Kel Mountain, and Simon Mountain meet, where the Orontes River merges with the Mediterranean. Although it takes its name from Simon Stylites, born in Antioch and acknowledged as a saint by both Catholic and Orthodox churches (known as Sama'an in Arabic), its Arabic name is Suveydiye, derived from the Arabic word "aswad," meaning black. This is because the shadows of the three mountains fall upon the city.

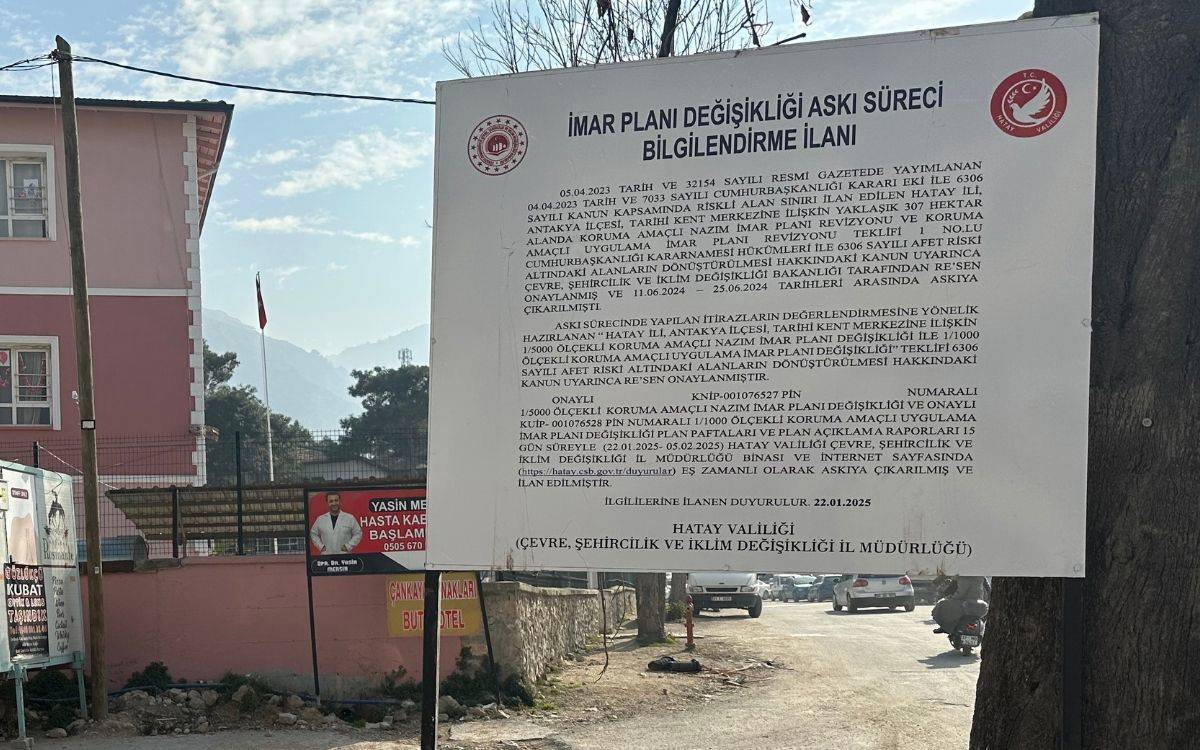

On February 6 and February 20, 2023, the shadow of the earthquake also fell on Samandağ. After Antakya and Defne, it became the third district where destruction was most intense. In Samandağ, where the number of collapsed and heavily damaged buildings exceeded 10,000, debris removal operations are still ongoing.

As in other districts heavily affected by the destruction, rural migration increased in Samandağ. In addition, residents of Armutlu, Gazi, and Elektrik neighborhoods in Antakya and Defne turned to villages as their homes were destroyed. The citrus, which is the main source of livelihood in the region, became a source of income for citizens who did not originally rely on this profession, serving as a means to momentarily forget the challenging days they were facing. However, months of labor did not bear fruit at the end of the year; the mandarins remained on the trees, decaying.

A forgotten village in Asi Valley

Yeşilyazı is a small village located approximately 6 kilometers from the Samandağ city center and 26 kilometers from Antakya, nestled in the valley through which the Asi River flows. The village, forgotten even before the earthquake, witnessed a significant increase in population afterwards. However, neither the infrastructure nor the superstructure is sufficient to meet the needs of this population.

The village road is full of surprises. It seems impossible to avoid the potholes while driving along the road that stretches along the mountainside. The air is filled with the scent of fallen mandarins on both sides of the road, accompanied by flies.

On the way to Yeşilyazı, we come across Ali Malik Kar, driving ahead of us in his car. We reach the village with him leading the way. At the entrance of a two-story house, there is a tea-like spot where the men of the village play cards. The greetings are swift when the game heats up. While Ali Malik details the reason for our visit, he also prepares coffee for us. The players seem uninterested, focused on the game, but their ears are attentive to us. When asked, "What has changed since February 6?" they begin speaking before the camera's "record" button is pressed.

"We couldn't get the village road paved in five years," says one citizen. Another adds, "We were forgotten even before the earthquake. And no one came after the earthquake, either."

However, the 72-year-old "young-at-heart" Sami Dede is also angry. "The mandarins remained on the trees. Not a single soul came here to ask what happened to this village," he says.

Ali Malik interjects, "Both the central government and the local government could have taken action. They haven’t. Now villagers cannot collect and transport [the fruits]. But if they had thought about it, the people of the village would have sold the product for much less than its cost, even 1-2 liras. Because they knew it would rot. If they had come, they could have bought this mandarin from farmers for 5-6 liras, not more expensive. Citizens would have eaten it for a cheaper price. Now, in İstanbul, I'm sure there is no such mandarin. Even if there is, it would be 30-40 liras."

"You see it, no need to explain"

Sami Dede was in Armutlu during the earthquakes on February 6. When his house collapsed, he moved to his village, Yeşilyazı, with his family. We walk together to the place where the houses and mandarin orchards are located. Two women making bread at the tandoor in front of the house greet us, saying, "Come, take it." We promise to visit them on the way back.

Sami Dede explains that in the land inherited from his father, his two brothers, son, and daughter have containers now. He shows each one individually, saying, "We bought these with our own money. The state has no function here. No one gave us anything." He tells us that his daughter and son are teachers, saying, "My daughter goes to her school in Antakya every day with her own car. My son is the vice principal at a high school."

There are thousands of mandarin trees right in front of the houses. The trees, which should remain green this season, are as orange as they can be. Mandarins are either on the trees or on the ground.

Sami Dede says, "You see it. No need to explain. The producers are in a bad situation this year. These should have been finished in the eleventh or twelfth month." As he continues to express his complaint, the mandarin he picks from the tree in a single stroke disperses in his hand, "What will you do with this? It's all rotten now."

There is approximately 4 acres of land, with around 30 tons of product. There is nothing to do.

When we ask, "Do you have another source of income?" we hear the common response of millions of citizens in the country facing the same situation: "I am retired. Until last month, I was receiving 7,500 liras. Thanks to them, they increased it to 10,000 now. I have nothing else."

On our way back, we also visited the women at the tandoor. They handed us a warm piece of bread. First eating, then working. One of them, Hayat, Sami Dede's wife, repeats, "We had three houses in Antakya, all gone. Here we came. All the mandarins here rotted away. My husband is retired, we have nothing else."

The other woman, a neighbor, introduces herself, "I am Elmas Kurd," and Hayat corrects, "Kurt." We struggle when speaking Turkish. She says, "My ears don't hear well," but in her native language, Arabic, she easily explains what they've been through.

"I have two sons and a daughter. One son went abroad after the earthquake. My daughter is married; when her house collapsed, she moved to her mother-in-law's. I live in the village with my husband and son. My son is studying and trains at Samandağspor. My husband works, takes care of an elderly man. That's how our life goes. I have no property, nothing. Thanks to Allah, nothing happened to my children; they are all healthy. Anyway, come, have more bread."

The one considered "lucky" is also troubled

As we left Yeşilyazı, we came across a citizen pruning mandarin trees by the roadside. Holding his hoe, he gently cuts the branches, and we inquire about his mandarins. Starting to speak, uncle Malik in his 70s says, "I was lucky."

"I had sold in bulk. The buyer picked them. But my uncle's children's mandarins remained on the tree. They couldn't sell them at all. It was like this this year. Our Samandağ traders' warehouses were already burned. There are no cold storage facilities. Where will they put it? What will they do with the fruit? Nobody buys, nobody asks."

"This is both our home and workplace"

A few days ago, when we went to Vakıflı, we noticed a complex structure at the entrance of the village. It was a two-story building, resembling a house on top but not exactly. There is also a warehouse in the back. Three men on the side were unloading mandarin crates from a large truck.

When we entered and greeted, we learned that this was a mandarin processing plant, and we spoke with the owner, Edip Kılınç. Actually, he is a farmer, continuing his father's profession. The three-story house in the center of Samandağ collapsed in the earthquake, and the products in the basement, which served as a warehouse, were buried under the debris. After the earthquake, he "took the risk" and established his own packaging facility, providing employment for about 200 people.

The place where he established the facility was originally a "summer house," but nowadays it serves as a home, office, dining room, warehouse, and packaging facility.

Edip Kılınç also expresses his dissatisfaction with local governments and the central government while explaining that Samandağ is an important center for mandarin production, with exports to many countries, especially Russia and Romania. "If storage areas were created for cooperatives, unions, or producers, the situation would not be like this. Unfortunately, since these did not exist, no one's property appreciated, nothing was collected; everything remained on the trees."

In summary, as Garbis Kuş, a mandarin producer from Vakıflı, also said, Samandağ residents "experienced earthquake after earthquake."

"The farmer's no product is profitable"

According to Ahmet Sever, the President of the Chamber of Agricultural Engineers of the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects (TMMOB) Hatay Branch, not only mandarins but none of the farmer's products were profitable in 2023.

The reason for this, according to Sever, was the lack of proper production planning. He emphasizes that calculations should have been made on what, how much, and in what quantity to produce, and support should have been provided to farmers accordingly. When these are not done, losses become inevitable.

Pointing out the increase in mandarin yield, Sever states that the farmer's hardship could have been alleviated with state subsidies. However, this option was not preferred, and the products remained on the trees.

"As the Chamber of Agricultural Engineers, we suggested at least a subsidy application by the state for mandarin purchases, with farmers being identified through provincial or district agricultural directorates, and the products purchased from them being sold to large supermarkets. Apart from this, we thought fruit juice factories should be established as soon as possible. We also suggested giving 2-3 mandarins to each child every day in elementary schools, like the milk given every morning. We have been talking about these since September. Because we foresaw what could happen with mandarins. But none of them were done."

2023 Maraş Earthquakes

On February 6, 2023, earthquakes with epicenters in the Pazarcık and Elbistan districts of Maraş, registering magnitudes of 7.8 and 7.5, respectively, resulted in destruction in 11 provinces in Turey’s eastern Mediterranean, Southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Anatolia. The earthquake also caused significant damage and losses of life in Syria and the tremors were felt in almost the entire Turkey, as well as in various parts of the Middle East and Europe.

Maraş, Hatay and Adıyaman suffered the heaviest destruction. In addition to these cities, a three-month state of emergency was declared in Adana, Antep, Elazığ, Diyarbakır, Kilis, Malatya, Osmaniye, and Urfa.

According to official data in Turkey, 50,783 people lost their lives, more than 100,000 people were injured, and 7,248 buildings, including public buildings, collapsed during the earthquake. Approximately 14 million people were affected by the disaster. After the disaster, more than 2 million people faced housing problems, and at least 5 million people migrated to different regions.

Hatay was hit by two more earthquakes, measuring 6.4 and 5.8 magnitudes, on February 20, 2023, with the epicenters in the Defne and Samandağ districts. Some buildings heavily damaged on February 6 collapsed due to these earthquakes.

(VC/AD/VK)