Following the passage of an omnibus bill in parliament last month, areas in Milas and Yatağan, located inland from the coastal district of Bodrum in Muğla, were designated for renewed mining activity under amendments to the Mining Law.

Besides affecting olive groves and pastoral herding, threatening over 30,000 villagers with displacement, this is an area that is historically within the ancient Carian region, rich with archaeological heritage sites that are facing further damage, and in some cases, outright destruction, in the wake of a long history of corporate malfeasance.

Since the 1980s, even prior to the legislation of the Mining Law in 1985, energy companies supplying environmentally costly, low-calorie lignite to power coal-fired plants in the Yatağan-Yeniköy-Kemerköy mining zone have endangered archaeological works. The village of Eskihisar, located on the prehistoric settlement of Stratonikeia, was evacuated in 1980 to make way for extractive industry.

Subsequently, efforts to strip mine these lands in 2018 destroyed the ancient road from Stratonikeia, a candidate as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, that linked its multilayered Hittite and Hellenistic ruins to the pagan-era sanctuary of Lagina, which receives tens of thousands of pilgrims at its monumental temple to Hecate every year.

New forestry regulation eases rules for mining, lifts reforestation requirement

Bronze Age tombs and workshops located along the same line have also suffered destruction, notes Selahattin Aydın, an archaeologist actively advocating to protect archaeological assets in the mountains of Latmos, locally known as Beşparmak, which stretch from Aydın to Muğla, where cave paintings detail over seven millennia of premodern culture.

“The basin from which coal was extracted for the thermal power plant in Milas was a region influenced by the Carian city of Keramos,” he told bianet. “Keramos had many small villages under its control. While the company was extracting coal from the region, many of the villages, workshops, and tombs were plundered.”

The village of Işıkdere followed the example of Eskihisar. “The vast cultural heritage beneath Işıkdere village was destroyed in two or three days after a series of perfunctory excavations,” said Aydın. “In order to avoid public reaction, an archaeological park was established in Ören for the cultural heritage transported from the coal field.

“The last time I saw it, the doors were locked. Extensive destruction had already occurred before the law was passed. This law will bring widespread destruction, and we don't know what we will lose.”

‘A multidimensional threat’

At the organizational level, the Turkish Foundation for Combating Erosion, Afforestation and the Protection of Natural Habitats (TEMA), has mounted a multi-tiered advocacy campaign against the omnibus bill of July 19, officially termed the “Draft Law on Amendments to the Mining Law and Some Other Laws.”

“The mapping of Group IV mining licenses carried out by the TEMA Foundation in 29 provinces since 2019 shows that forests, agricultural areas, drinking water basins, and cultural heritage areas are largely subject to mining licenses,” Deniz Ataç, head of TEMA, told bianet.

“According to the study, an average of 67% of the total area of these provinces has been licensed for Group IV mining,” she added, referring to mass tracts of land across the entire country of Turkey.”

Ataç stood up in parliamentary discussions on Jun 19 to protest unregulated mining, highlighting how this legislation would affect the sites of global cultural heritage that survive, however, precariously, within Turkey.

“This law is not merely a technical regulation,” she said. “It poses a multidimensional threat to nature, production areas, cultural values, public health, and rural life.

“With the amendments made to the Mining Law, our forests, wetlands, pastures, and protected areas are in grave danger.”

Protection efforts sidelined

Currently unemployed, Aydın is unable to find stable work in his professional field, sharing a common fate with a number of colleagues whose work is sidelined by top-down market forces in the administration of Turkey’s tourism sector, which generally relegates short-term, decorative attention to archaeological zones near popular coastlines.

Landlocked sites in agricultural regions, despite their importance for the scientific community, are undervalued by corporate and government lobbies, making them more vulnerable to the streamlined interests of extractive energy investments.

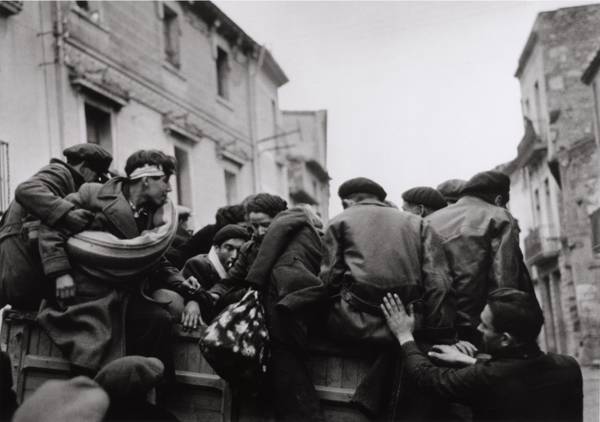

“I strive to be a barrier by traveling from village to village, amplifying the voices of local people, and creating an anti-establishment discourse,” said Aydın, who cites numerous examples of disaster and corruption in the archaeology sector, such as at the ancient sites of Side, Kyme, Bergama, Hasankeyf, and Karabel. “I foresee that solidarity will grow even more against this attack, which directly threatens our very existence.”

Amendments to Mining Law

A 21-article omnibus bill was passed on Jul 19. It includes an amendment to the Mining Law, outlined in article 11 and publicly dubbed as the "super permit," which allows the use of agricultural land, including olive groves, for mining operations under certain conditions.

Also part of the omnibus law, the provisional article 45 added to the Mining Law designates two separate olive-growing areas in the province of Muğla as mining zones. The lignite extracted from these areas will supply nearby thermal power plants.

Critics argue that the amendment undermines environmental protection and violates the Olive Law. Since its introduction in parliament, the bill has been protested across Turkey’s southern and western regions, where most of Turkey's olive groves are located.

The law allows the Energy and Natural Resources Ministry to authorize mining in areas officially registered as olive groves or where olive trees are currently located, if the mining activity is aimed at meeting electricity needs and cannot be relocated elsewhere.

In such cases, the olive trees may be transplanted within the same province or district, and temporary facilities may be built to support the mining activities, provided that the public interest is taken into account.

According to the new legislation, mining companies will be required to pay an additional fee equal to their operating license cost each year for land rehabilitation efforts. If state-owned land is needed to establish new olive groves or relocate trees, it may be leased directly to former landowners for ten years at market value, subject to approval by the Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change Ministry.

The law also extends several incentives for renewable energy investments. The Energy Market Regulatory Authority will be authorized to issue urgent expropriation decisions until Dec 31, 2030, to secure land for licensed renewable energy facilities.

Also, a discount of 85% will apply to permits, leases, and easement procedures for renewable energy projects operational by that date.

(MH/VK)