Turkey's Mining Law No. 3212, enacted in 1985, faces yet another amendment following a series of draft bills in the last decade in what is widely seen as a referendum on the national agricultural economy as olive groves, forests and pasturelands are, again, threatened by the energy industry.

Despite hundreds of court cases and ongoing spats between activists aligned with affected villagers, law associations and environmental groups, the amendment is slated for approval despite a record 26-hour parliamentary debate on Jun 20 moderated by the Industry, Trade, Energy, Natural Resources, Information and Technology Committee.

Amid protests by local groups across various places in Turkey, the general assembly is expected to convene this week and pass the omnibus bill, with Article 11 amending the Mining Law, streamlining coal extraction by deregulating the Environmental Impact Assessment reports that have ever been the basis on which appeals are brought to court.

“To get permissions, licenses from governmental organizations and municipalities, mining and energy companies had to wait for the Environmental Impact Assessment report to be approved by the Environment Ministry. Now, the proposal, which really undermines all of our work, says they don't have to wait for approval,” Neşe Tuncer, a volunteer for the Muğla Environment Platform (MUÇEP), told bianet.

MUÇEP has been instrumental in fighting recent attempts to amend the Mining Law with Turkey’s agriculturalists, notably during the struggle to preserve the forests of Akbelen from lignite mining from 2019 to 2023, resulting in mass deforestation and an unproductive mine.

The abject inoperability further confirmed the notion that, more than energy independence and national sovereignty, this legislation is a backhanded ploy for private, multinational corporations to secure short-term capitalist gains through lucrative government subsidies.

‘Personal delivery’ for companies

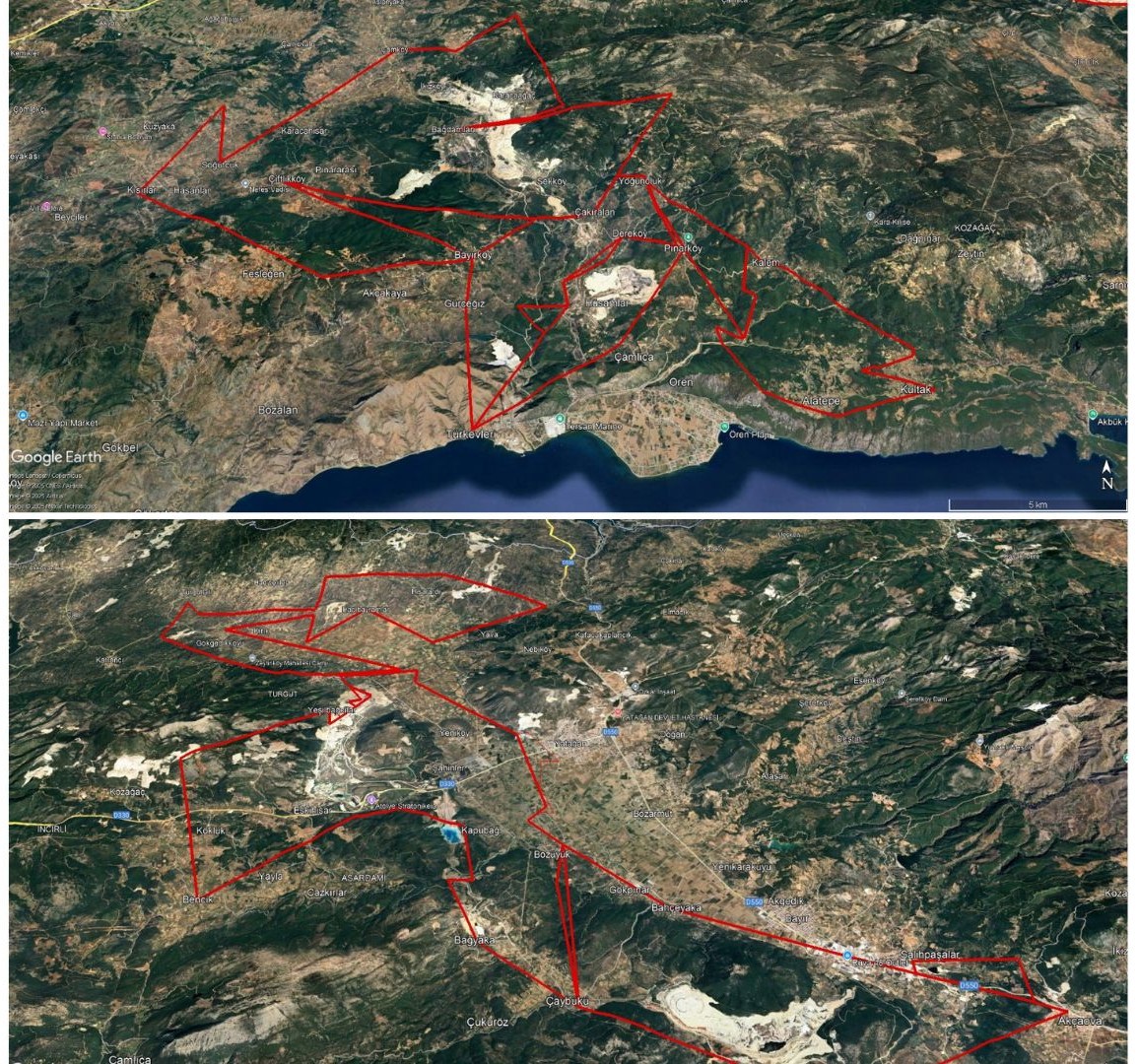

A provisional article in the amendment lists coordinates corresponding to three lignite mining sites in Muğla, an issue also raised by opposition members during the committee's 26-hour session.

“And in Article 11 of this proposal they say they are adding a temporary article to article 45 of the Mining Law. And they give some coordinates. These coordinates are exactly the same as the permit coordinates for lignite mining in the coal power stations in Milas and in Yatağan," Tuncer said. “It was evident that this is a personal delivery mode for these two companies that manage the three coal power stations in Muğla.”

These companies are YK Energy, a joint venture of Limak & IC İÇTAŞ Holding in Milas and Bereket Energy of Aydem Holding in Yatağan, both in Muğla in the Aegean coastal region, which is responsible for over half of Turkey’s olive production.

Energy company wants villagers to cut down their olive groves in İkizköy

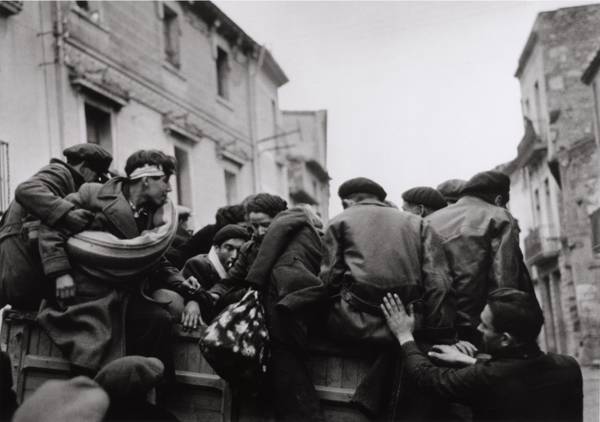

“There are 48 villages that are directly affected by these coordinates. And the 33,400 people who live in these villages, nobody says what's gonna happen to those people when this whole area becomes an open, coal pit,” informed Tuncer, who is based in Muğla’s Milas district, organizing buses for rural communities to and from the capital Ankara, staging protests with broad coalitions and campaigning to petition MPs.

Meanwhile, the Mining and Petroleum General Directorate (MAPEG), "acts like a consultant" for the mining and energy companies, obtaining their permits, licenses, making life much easier for them, according to Tuncer.

'Greater pressure from industrial lobbies'

According to MUÇEP’s calculations, these coal power stations would power only 2.5% of electricity demand in Turkey. And as there is a comprehensive interconnectivity system channeling electricity infrastructure throughout the country, the location of the resources are entirely arbitrary.

The government, in turn, has proposed infeasible and inappropriate returns, such as the replanting of olive groves and communal reimbursement, none of which satisfies the ecological or socioeconomic needs of the targeted villages and their greater environments.

“This time, the amendment doesn’t just erode the Olive Law, it directly contradicts it. By introducing vague ‘exceptions,’ it opens the door to systematic destruction of protected groves,” Greenpeace Turkey’s Climate & Energy Campaign Consultant Emel Türker-Alpay told bianet, referring to Turkey’s Olive Law, enacted in 1939, which has protected olive groves from industrial encroachment. “It’s not a gray area anymore. It’s a blueprint for deregulation. And it threatens to normalize legal contradictions across other environmental protections as well.”

“This time, the scale of opposition is even greater, but so is the pressure from industrial lobbies. Whether we succeed again depends on how long and loud we keep speaking out,” Türker-Alpay explained. “This isn’t just about olives. It’s about protecting the last democratic space for resisting destructive industrial expansion.

“Olive groves are the backbone of entire regional economies, ecosystems, and food cultures. Threatening them threatens everything connected, soil, water, bees, birds, farmers, and future generations."

High court annuls regulation opening olive groves to mining

(MH/VK)