Turkey has launched air raids in areas controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Northern and Eastern Syria on October 5. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), civilian settlements, dams, power plants, and irrigation networks, among other public facilities, suffered permanent damage, and at least 45 people lost their lives as a result.

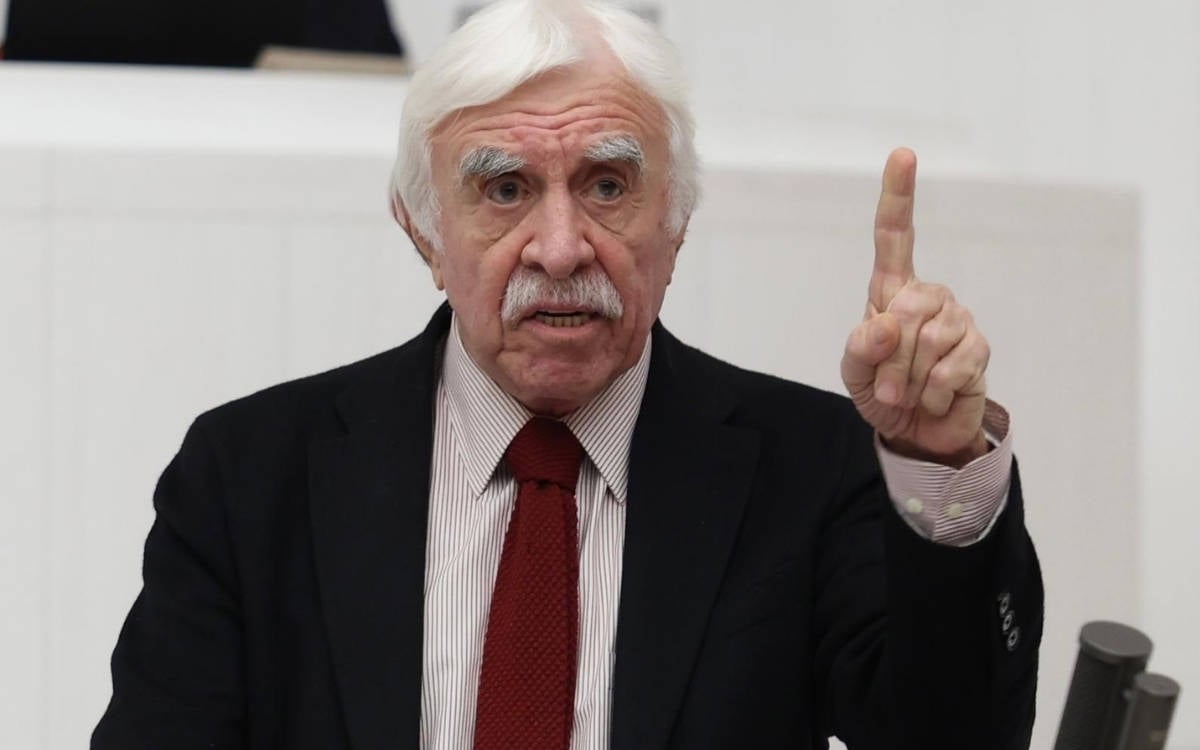

We spoke with academician Güneş Murat Tezcür, the Director of the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University, about whether these operations in Rojava would lead to a ground offensive, about the Palestine-Israel conflict, and about the developments in Turkey in recent years.

Turkey's air operations

Turkey started air operations following Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan's statements regarding Northern and Eastern Syria and targeted structures such as oil wells and water reservoirs. This was a method that Turkey had not used "openly" before. What do you think about this?

From a long-term perspective, Rojava is currently a region under the control of the YPG/YPJ. It was established with the support of the Kurdish forces there in response to the ISIS attacks in 2014, during the Obama administration. We are talking about a process of approximately nine years. In September 2014, Kobanî was completely under siege. There were discussions about the "fall" of Kobanî, but of course, the course of the war changed after the US intervention and this had implications for politics in Turkey as well.

Now, when we look at it, we see that the most significant reason for the survival of Rojava and the Kurdish structure there is the support provided by the US Air Force. The number of US troops in the region is small, but the air force is decisive. Turkey is, of course, pressuring the US not to provide this support. In 2019, when Trump was in office, the US attempted to withdraw from the region completely, but when the administration faced criticism not only from Democrats but also from Republicans, it abandoned the withdrawal.

In recent years, Turkey has taken control of part of the region with its operations and has been challenging this relationship ever since. These challenges sometimes receive strong responses from the US side, such as when US shot down a drone of Turkey.

On the other hand, looking at Rojava's current policies, it is not a region that is a top priority for the US right now. But without the US's air cover in the region, there aren't many factors to prevent Turkey from entering the region. We can think that this is why Turkey is trying to minimize the region's power and resources in some way.

International support for Rojava

Considering the countries other than the United States, do you think that international support for Rojava has decreased?

In the left circles in Western countries, there is still sympathy and support for Rojava, of course. But, as we've seen with the Palestinian issue, people's sympathy for a people and their struggle doesn't necessarily change the outcome. Ultimately, military power becomes decisive. Yes, Rojava is not as prominently featured in Western media as it was five or six years ago. Even if it were, its impact would be limited in the end. Military power dominates in realpolitik in some way. I believe the Palestinian cause is the greatest example of this.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) reported a total of 45 casualties in Rojava, at least 10 of whom were civilians. How do you evaluate these losses in the context of international agreements that Turkey is a party to?

This issue is of course very topical due to the Israel Palestine war. When Hamas raids various places in Israel on October 7 and kills people this is directly designated as "terrorism," which I think is correct. However, the classification can become more ambiguous when a state employs disproportionate force, leading to civilian casualties. Because the states usually argue that they are not targeting the civilians but the armed militants. However if there are civilians in that region they also suffer and the ambiguity disappears with the concept of disproportionate force.

A state would be considered to have committed a war crime when it directly and intentionally targets civilians, but in practice, this is often not the case. What typically occurs is the use of disproportionate force. The most prominent example of such violence can be seen in the case of the United States during its operations against the Islamic State in Raqqa in 2017, and a similar situation arose in Mosul. When you target armed militants, the civilians around them are also affected and killed. This is where they develop their argument. "Collateral damage" is one of the most significant arguments used by Turkey to justify self-defense, and it is employed by many other states as well. And for many states, there is often no real consequence for such actions.

Some lives considered more valuable

Could you explain the concept of disproportionate force a bit more?

From a philosophical perspective, human life is often considered a universal concept. As emphasized in many United Nations agreements, this is the ideal, but in reality, it's not always the case. Some people's lives are considered more valuable than others. This is a situation that reflects power imbalances both globally and locally.

For example, in the case of Palestine, a significant number of people are being killed, but the impact of their deaths is often considered less significant compared to the impact of an Israeli being killed. This is at least how it is often perceived in international public opinion. The difference can be due to factors such as people's skin color, religion, or the languages they speak. In the Middle East, we can already see this starkly, especially since the 2003, the invasion of Iraq. We're talking about a region where tens of thousands of people have died in the past 15 years, and the deaths of people in the Middle East have become somewhat normalized in terms of world public opinion and social movements. The same can easily be said for Rojava and the Kurdish region, of course.

[Minister of Interior] Hakan Fidan had some visits to the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq before the operations. How do you evaluate these visits?

The KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party) has had a long-standing collaboration with Turkey. This relationship faced some challenges during the 2017 referendum crisis, but it was somehow repaired. When we consider the region under Barzani's influence, Turkey is a significant commercial partner, particularly in Duhok and Erbil. It also serves as a balancing factor against Iran and the Baghdad government.

Turkey has conducted extensive operations in the Behdinan region (immediately south of the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq), and one could say that Turkey brought the war from Botan to Behdinan. This is not something the Barzani government necessarily opposes. While both the PKK and the KDP are Kurdish movements, it doesn't mean they always share a common ground. Therefore, in the conflict against the PKK within Turkey and the YPG in Rojava, the position of the Barzani family is generally aligned with that of Turkey. Especially since the rift during the Bush administration, Turkey's geopolitical interests have overlapped with those of the Barzani family in many ways.

The Barzani family has become somewhat accustomed to these attacks. They may not be willing to support a more extensive operation by Turkey, but they are well aware of Turkey's military activities in the region, and rather than opposing Turkey Barzani government is more focused on opposing the PKK, saying: "We are suffering from your conflict here, and therefore, you shouldn't be here."

Are these attacks preparing the ground for a ground operation?

It's not very easy to predict this. Especially after the October 7 attacks, Pandora's box has been opened, in any case. The US is still the most influential actor in the Middle East, but whether it's a hegemonic actor is somewhat debatable. Because, in fact, the real strategy of the U.S. has been to shift more towards the Pacific, especially focusing on China, since the time of Obama. Russia's invasion of Ukraine disrupted this strategy to some extent, but the Middle East has always been attempted to be pushed into the background because the US no longer wants to stay militarily in the region. Therefore, the Middle East, which was once given great importance, is now a region that is somewhat half-heartedly valued.

The October 7 attacks certainly changed this situation on the ground. For example, Biden went to Israel, and from there, he will go to Jordan. Middle East politics is becoming important for the US, but predicting its aftershocks is not easy. Israel is an important ally for the US, but on the other hand, there is also the relationship between Saudi Arabia and Israel. Whether Turkey will play a role as a mediator, how much the US wants to stay in Syria, all of these are uncertain. But, of course, as long as the US doesn't completely withdraw its air shield from the region, a comprehensive ground operation by Turkey is not very likely.

Now the Palestine-Israel war has added on to this.

In the US public opinion, there are three different attitudes towards the Palestinian-Israeli issue. The first one, unsurprisingly, is the stance of the Republican Party and Evangelical Christians. They view Israel as representing democracy and civilization in the face of barbarism, and they say, "We should support Israel to the end in the face of the terrorist attacks on October 7." This perspective can lead to support for all policies, including ethnic cleansing in Gaza.

The policy pursued by the Biden administration is somewhat different. They designate Hamas as a terrorist organization but they do not support a permanent occupation of the Gaza by Israel. This of course is the result of the attitudes of the left in the US. The US left has positioned itself in a more critical position to Israel with the change that took place in the last 15 years. The left wing of the Democrats argue that Hamas is a result. They argue that Hamas is the reflection, the result of the occupation and colonial policies pursued by Israel against Palestine since so many years.

Israel has been conducting airstrikes in Gaza and may launch a ground operation, with the aim of targeting Hamas infrastructure and try to impose a complete blockade on Gaza as in the past. However, the presence of Hezbollah and Iran in the region adds complexity to the situation. If Hamas were significantly weakened or removed from power in Gaza, it's unclear who would govern the territory, creating a significant uncertainty. It's worth noting that even powerful military offensives may not always lead to long-term changes, and a lasting solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict remains elusive.

Being powerful, being just

Hakan Fidan accusing Israel of "theft" reminded people of the Afrin operation. What are your thoughts on this?

In international politics, is there a fundamental moral argument for the just or is the most significant reason for being just being powerful? Israel's dominance over both the West Bank and Gaza is highly problematic from the perspective of international law. And this situation has remained unchanged since 1967. The number of settlers keeps increasing, and Palestinians are left with very limited living space. The powerful, even if not morally right, can somehow enforce their authority. And, of course, they develop new arguments: "We gave the Palestinians a chance to make peace, there was the Oslo Process in the 90s, but then terrorist attacks emerged."

Looking at it from Turkey's perspective, we see that they have been relying on a parallel argument for years. People talk about conflicts and resolution processes, how the process was terminated. It must be clearly stated that, after 2015, during the intense period of conflict, the Kurdish armed movement did not succeed. With this situation, Turkey became capable of imposing all its dynamics on the Kurdish region in one way or another. While a moral and political interpretation may sometimes appear more appealing to the people, this is what has been happening.

So such interpretations do not seem rational to you?

Beyond rationality, it's not necessarily a convincing argument for the other side. This is an age-old debate; in colonial processes, you often have to resort to so much violence that the dominant power is somehow compelled to make concessions. This approach can sometimes be successful, but other times it backfires. Because if you use too much violence, the other side can become provoked and may inflict even more cruelty on you, just as Israel has done with extremely ruthless policies. And unfortunately, this cycle of violence may not change the course of politics.

The Kurdish issue was on the global agenda for a long time, but it's not easy to say that it's now being addressed in the same way, especially after 2017. Perhaps Trump's withdrawal from Syria in 2019 generated significant international attention. When we look at the last three to four years, we can see that the Kurdish issue has faded into the background. The current conflict in Palestine might provide Turkey with more maneuvering room on this matter. Erdogan's role as a mediator is also not an impossible development.

I don't want to paint an entirely negative picture, but when we look at the developments in both Turkey and the Middle East over the last 20 years, it's not very encouraging. With some developments that directly affect at least one or two generations, people's youth dreams and their struggle for democracy can suddenly be distrupted. And it can take decades for a new wave or movement of struggle to emerge.

Of course the elections was another a significant turning point. Turkey is rapidly advancing on the path to becoming a country where autocracy is normalized. The question of the legitimacy of the one who holds power has been discussed since Thucydides and Machiavelli. When we look at Middle East politics, we can come to this conclusion as well. Those who lack power are forced to accept the hegemony. When they do not accept hegemony, they face a very harsh response, as the Kurds have experienced.

During the Arab uprisings in 2011, in countries like Egypt, Tunisia, and even before the devastating wars in Syria, many people felt happier and freer during street protests, thinking they would live in more prosperous countries. Now all these countries are in a much worse condition, including Turkey.

Shrinking intellectual space in Turkey

Speaking of Turkey, it's worth noting that, especially from 2005 to 2015, there was a vibrant intellectual space in the country. A lot of research and discussions were taking place, and this was reflected in newspapers and television as well. From my perspective, I believe that in the past eight years, this intellectual environment has completely disappeared in Turkey. Yes, some people can still write and discuss important topics that lead to meaningful debates, but it happens in a more closed environment. After 2015, with the full display of violence, along with autocracy, such an intellectual space has all disappeared. This is very saddening.

About Güneş Murat Tezcür

Academic.

He is the director of the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University.

His academic research primarily focuses on political violence and identity, democratic struggles, and social movements. Among other research topics, he also works on the issue of people participating in mass-level violent actions. His work has been published in several leading international academic journals.

He served as the editor for the book "Oxford Handbook of Turkish Politics."

(TY/PE)