In an interview with Dr. Amy Austin Holmes, we delved into the intricate dynamics of Turkey's Rojava policy and the presence of Turkey-backed armed groups in the region.

A guest researcher at the George Washington University's Institute for Security and Conflict Studies, Dr. Holmes is known for her fieldwork. Dr. Holmes, who previously was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), an American think tank, and served as a researcher at the Woodrow Wilson International Research Center, responded to bianet's questions.

Dr. Holmes, who authored a book on the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, states, "There are compelling economic, political, and security reasons pointing towards a peaceful coexistence between Turkey and the Autonomous Administration. These factors may also be part of the negotiation process."

Moreover, she highlights the disruptive impact of groups affiliated with the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army (SNA, formerly known as the Free Syrian Army), attributing to the region's ongoing "chaos and instability."

You worked in Rojava for four years and wrote books. What insights can you share about the region?"

Actually I made my first trip to Rojava / Northeast Syria in 2015, 8 years ago, and have gone back almost every year since then. I witnessed how the region around Tel Abyad was liberated from the Islamic State in June 2015, which allowed the two cantons of Kobane and Cazira to be geographically connected for the first time. Then in 2019, part of that area was then occupied by Turkey after the phone call between former President Trump and Erdogan. Despite huge challenges and setbacks, I’ve seen how they’ve developed local governance structures that represent both an important form of decentralization and empowerment of women. I write about this in my new book: Statelet of Survivors: The Making of a Semi-Autonomous Region in Northeast Syria.

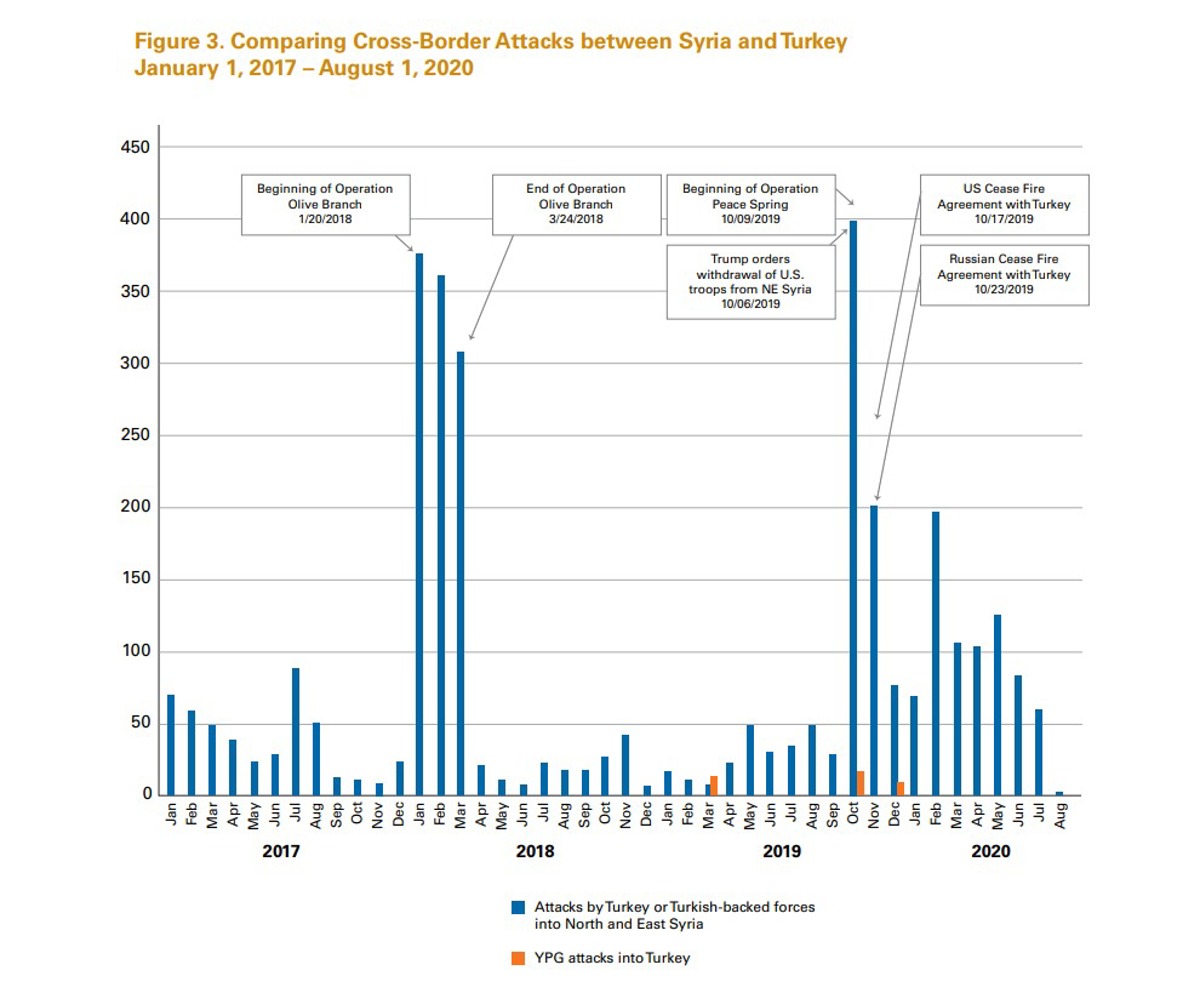

On October 5, Turkey conducted an airstrike on Rojava, resulting in at least 45 casualties and damage to 55 facilities. Your report covers Turkey's attacks on Rojava from January 2017 to August 2020, revealing 3319 attacks from Turkey to Rojava and 22 from Rojava to Turkey targeting civilians. Could you elaborate on the methods you employed in preparing this comprehensive report?

My analysis of the Syrian-Turkish border conflict is based on both quantitative and qualitative research methods. In order to conduct a quantitative assessment of the conflict based on impartial sources, I created a new dataset using Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED), with the help of two research assistants. This information is supplemented with qualitative interviews I conducted on the ground in Syria, including in the region on the frontlines held by opposing forces: Turkey and the Turkish-backed proxies on one side and the US-backed SDF on the other.

Due to the sensitive and politicized nature of the conflict, every effort was made to only use sources that are impartial in nature. This means that the database was constructed using ACLED instead of sources from either party to the conflict. I have also refrained from using official statements issued by either side of the conflict: neither from Turkish government or military officials nor from officials of the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria (AANES) or the SDF. The ACLED data which I analyzed is one of the most widely-used datasets available, and provides detailed descriptions of each event including the actors, location, time, casualties and injuries, and the type of violence used.

In order to create the new dataset on the SyrianTurkish border conflict, we downloaded all events registered by ACLED, beginning with the earliest date available for both countries, which was January 1, 2017. We then specified the relevant actors in the conflict. These include the Turkish military as well as Turkish-backed factions which ACLED identifies either by the names of the individual factions, such as Hamza Division, Sultan Murad, Jaysh al-Islam, Ahrar al-Sharqiya, Ahrar al-Sham, and so forth, or as “Operation Peace Spring Forces” or “Turkish-backed forces,” as well as the SDF and YPG. Between January 1, 2017 and August 1, 2020, ACLED recorded 3,900 incidents of attacks from Turkey into Syria, including those within Turkish-occupied parts of Syria.

Because we are only interested in those attacks that target the SDF/ YPG or civilians, we went through all 3,900 incidents and excluded events that involved infighting between Turkish-backed forces from our dataset, unless civilians were killed as a result of the infighting, in which case we included them.

However, it should be emphasized that even if no civilians or SDF were killed during such episodes, they may be seriously harmed in other ways. For example, Turkish-backed forces often fight over the stolen property of civilians. Infighting between SNA factions contributes to chaos and instability, which is one of the main reasons that civilians who fled the Turkish invasions are still unable or unwilling to return to their homes.

The following are two examples of infighting between Turkish-backed factions that we excluded from the total count of events. Although civilians were clearly impacted in both cases by militias fighting over stolen property, we did not count events like these in our database because civilians were not killed or directly targeted. The first is an example of infighting between different militias in the Turkish-backed SNA. Because of the large volume of events recorded by ACLED and the necessity of analyzing each individually to ensure methodological rigor, we have excluded events that occurred after August 1, 2020. The following incident is an example of serious clashes between Sultan Murad and Hamza Division, which are both part of the Turkish-backed SNA, that took place after August 1.

“On 6 September 2020, Sultan Murad Division clashed with Hamza Division in Qabour Qarajna in the countryside of Tel Tamer in Al-Hasakeh following a dispute over the takeover of properties owned by displaced civilians. Clashes were accompanied by the exchange of shelling. Several houses were burned during the clashes. Clashes in Um Shu’ayfah, Mahmudiyeh, Aniq El Hawa, Qabour Qarajna, and Manakh resulted in the killing of an unknown number of fighters from both sides.”

There are also cases of clashes within the same Turkish-backed group, as this incident makes clear:

“On 6 April 2020, internal clashes erupted among Turkish backed Sultan Murad Division whom are operating under OPS in Ras Al Ain city… after a dispute between the two groups over stealing a washing machine, which resulted in seriously injuring four of them.”

After excluding all episodes of infighting between different and within the same Turkish-backed groups that did not result in civilian deaths, we were left with a total of 3,572 incidents. This included incidents that involved securing the Turkish occupation of Syrian land: Turkish patrols, building Turkish military bases or outposts inside Syria, imposing curfews in Turkish-held regions, detaining or arresting civilians who live in Turkish-held areas, and non-violent transfers of territory. Although these incidents may violate international or human rights law, or involve human rights abuses such as arbitrary detentions of civilians, we excluded these from our final tally in order to ensure our comparison remains as accurate as possible.

The SDF/YPG does not control territory inside Turkey, and hence there are no such comparable events on the Turkish side of the border. We therefore eliminated all incidents that involved securing Turkey’s occupation of Syrian land, so that our comparison is systematically defined only by attacks that affect civilians or members of the security forces on the opposing side. Excluding such incidents, the total number of attacks from Turkey or Turkish-backed forces targeting civilians or the SDF falls to 3,319.

We then turned to an analysis of attacks from the Syrian side of the border into Turkey. During this same time period (January 1, 2017 until August 1, 2020) ACLED registered only 22 incidents of cross-border attacks by the YPG/SDF into Turkey. Of those, 10 we were not able to verify with independent sources. In other words, we can only credibly account for 12 incidents.

Furthermore, these 12 incidents all occurred after Turkey launched Operation Peace Spring in October 2019. The only cross-border incidents from Syria into Turkey that happened prior to the October 2019 intervention were four incidents allegedly involving drones that were recorded in March 2019. ACLED cited Anadolu Agency, Daily Sabah, and SETA, which are all close to the ruling AKP party. When we checked the referenced articles, we discovered that the wording in the articles was very similar, and that they all cited one single anonymous source. We were not able to verify these incidents with independent sources. It is of course possible that these incidents did occur but were not widely reported because they were considered insignificant. For example, the four drone incidents reported by Anadolu Agency resulted in no casualties. It is also possible that the incidents did not take place at all, but were fabricated or exaggerated by the pro-Erdoğan media to justify the Turkish intervention.

In short, the data shows that Turkey’s interventions into Syria in 2018 and 2019 were based on disinformation. There was no real threat to Turkey by the SDF or YPG inside Syria. My analysis of the ACLED data is corroborated by the highest-ranking American diplomat on the ground at the time: Ambassador William Roebuck.

Do you have any data on the period after January 2020? What is the situation in the last three years?

Yes I have been working on this, but it is not yet ready to be published.

In a 2019 Washington Post article co-authored by you and Wladimir van Wilgenburg, you argue that "Erdogan's real plan is to drive Kurds away from the border and radically change local demographics under the guise of fighting terrorism and 'securing' the border." What drives Turkey's perception of the Syrian Democratic Forces as a threat, and what type of border organization does Turkey envision? Furthermore, why is there a lack of dialogue with Rojava, as opposed to the ongoing discourse with the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq?

By defeating the Islamic State in Syria, which was on Turkey’s border, the SDF actually protected Turkey and contributed to securing its border from the threat of Da’esh. In other words, I could see a scenario in which Ankara eventually comes to acknowledge that not only is the SDF not a threat – but actually contributes to Turkey’s security. Or at the very least, tolerates an SDF presence in northern Syria as preferable to the Russian and Iranian-backed Assad regime.

Furthermore, if Turkey wants some of the millions of Syrian refugees who live in Turkey to be able to voluntarily return and safely live in Syria, then it makes no sense for Turkey to destroy one of the few places in Syria where refugees could potentially return and live without fear of the Assad regime (namely Rojava / Northeast Syria).

Finally, there is a huge potential for Turkish investors to invest in northern Syria, through General License 22, which allows investment in non-regime held parts of Northeast and Northwest Syria.

There are potentially quite powerful economic, political and security incentives that all point in the direction of peaceful coexistence between Turkey and the Autonomous Admininstration of Northeast Syria, which could potentially also include negotiations. However, the PKK attack in Ankara on October 1 made all this much more difficult. There needs to be an immediate return to a ceasefire.

Following Turkey's recent attack on Rojava on October 5, President Joe Biden asserted that "Turkey's operations in northern and eastern Syria pose a threat to US national security." How do you interpret this statement?

That statement was a continuation of Executive Order 13894, which had originally been declared by former President Trump in response to Turkey’s 2019 “Peace Spring” intervention.

Can you elaborate on the approach of President Joe Biden's administration to Rojava? Specifically, what is their stance on recognizing Rojava's status, and what policies are they formulating?

In Syria, the United States remains mainly focused on the enduring defeat of ISIS, providing humanitarian aid, and accountability for the Assad regime. However, this past spring President Biden and First Lady Jill Biden hosted a Newroz celebration in the White House.

Are there concerns within the US and Western countries about recognizing Rojava's status? While discussions often revolve around combating ISIS, explicit statements on Rojava's status seem scarce. Why is this the case?

I understand the question and interest in trying to understand the approach of Western countries. However, I actually think there needs to be more attention paid to Intra-Kurdish dynamics. If Kurds in Iraq and Syria would find ways to work together, for example, by ensuring that the border crossing at Fishkhabour / Semalka functions smoothly, that would not only improve the situation for ordinary people who need to cross the border, but I believe it could also go a long way to gaining more support from Western countries.

What actions need to be taken for Rojava's political will to be recognized, and how might the acknowledgment of Rojava's status impact the broader region?

It would be good if members of civil society in Turkey would visit Northeast Syria to view the situation there themselves. Over the past few weeks since the attack which the PKK claimed responsibility for in Ankara on October 1, Turkey’s drone campaign has targeted about 50 schools in Northeast Syria. The Autonomous Administration has warned that the entire education system could collapse. School teachers and university professors in Turkey could offer to teach online courses at some of the universities and schools in Rojava as a way of supporting the new education system. There is a lot that could be done – including simply by providing news coverage of the reality in Rojava / northern Syria – so people in Turkey will understand what is happening there. (RT/VK)