I stand at the crossroads of three countries in Şemdinli.

It is not easy to get from Istanbul to the district of Şemdinli that sits about an hour of travelling away from Iraq and Iran. Şemdinli is where mountain ranges awash in greenery start, following a five hour long minibus trip over winding roads.

The locals in the town that consists of two avenues and 20,000 people are relatives of the Kurds in Iraq and Iran. Most of the youngsters and the men are bilingual and speak Turkish as well, but the majority of the women understand only Kurdish.

I arrived in Şemdinli at dusk, as clashes entered their 13th day on Saturday. I learned the district was relatively calmer in comparison to the preceding days; "tactics" or a planned visit by a delegation of deputies from the opposition People's Republican Party (CHP) are among the reasons cited.

A plume of smoke rising from Mt. Goman never seems to fade even though artillery fire and the bombardment cuts down at day time. Helicopter gunships keep circling over the hill, while special operations vehicles are on constant patrol down below.

As soon as I exit the teachers' lodgings across the mountain, special operations units come down and ask "Who are you? Why did you come? How long will you stay?" They retreat, however, after checking my journalist and identity cards.

The district center is far less crowded than usual at day time; it becomes nearly desolated after the "iftar," the traditional evening meal that marks the end of the daily fasting in the month of Ramadan.

Streets are normally jam-packed until midnight in the Ramadan, I have heard.

Artillery fire commenced at 23:00 on Saturday and kept going until morning. Even those unaccustomed to it like me become inured to the thundering of artillery fire accompanied by Kurdish hymns in the background after a while.

The clashes are raging over an area 600 square kilometers wide, including Mt. Goman and Mt. Efkar across the district center.

Over 500 villagers were forced to evacuate their homes in the days that followed the eruption of the conflict.

The PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party) has run "identity checks" on many village roads, and even on the road to Yüksekova. The "identity cheks," which are cited as the main reason that ignited the conflict, are a means for the PKK to assert its presence, according to what I have heard.

"Hit and run" turns to "hit and stay?"

BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) Deputy Esad Canan who accompanied us in our car during our trip from Yüksekova to Şemdinli said the PKK had revised its tactic from "hit and run" to "hit and stay," allowing it to establish "area control" in Şemdinli.

Canan also said the officials' muted response to the issue was due to the state's loss of control in the area.

"We [were not allowed to] enter through the borders of our district with the mayor, and this shows the state is hiding something," he said in regards to their aborted attempt to enter a neighborhood in downtown Şemdinli.

The ongoing clashes are the most protracted ever, he also added.

"We are just like back in the 1990s. There is a de facto 'OHAL' (state of emergency,)" Canan said.

Deputy Canan also elucidated on the reasons as to why the conflict had broken out now and why in Şemdinli in particular:

"Şemdinli is where the PKK launched its first raid in 1984 in tandem with Eruh; it bears symbolic significance. Secondly, it [represents] a reaction against the state's claim to have finished the PKK off and Prime Minister Erdoğan's rhetoric of intervention against the formation of a Kurdish [entity] in Syria," Canan said.

"The PKK is telling the state to pay attention to Şemdinli rather than picking on Syria," former Hakkari Deputy Hamit Geylani also explained, as he kept us company at an "iftar" meal where we dined together with all the other reporters in the district.

No explanations, merely allegations

The question of exactly how many troops and PKK members lost their lives in the conflict is still shrouded in mystery. Reports indicate that 10 soldiers died until now, including in the attack in downtown Hakkari. There is talk of bodybags being picked up from hospitals.

Further claims are also abound that the troops who died were mercenaries and that the Turkish Armed Forces had mistakenly killed 17 soldiers. All this is nothing but hearsay, however, as authorities have barred all access into the region.

The PKK announced that it had lost four guerillas. Families keep arriving in Şemdinli to pick their funerals up, but officials deny them access into the area for reasons of security.

Off to nearby villages, or to Şemdinli

Despite announcements by the district governor's office that they did not order the evacuation of the villages, locals have already abandoned their animals and fields, with their doors still wide open, to take refuge with their relatives in the closest villages, or in downtown Şemdinli.

Some villages are still in the line of fire; they have power outages and are running short on food supplies. Those who attempt to leave their villages are unable to do so because security forces do not allow them to; or they do so by putting themselves at great risk.

Mayor Sedat Töre says they have established a support unit for the displaced families while delivering provisions of food and clothing to them, but they are also at a loss as to how they will proceed in the future.

The district governor's office is yet to deliver a statement on the issue.

Villagers tell their tales

75 year old Ayşe Kaplan from the Aşağı Yiğitler village said the bombs had started raining upon them like a bolt out of the blue and that they immediately took shelter in their homes.

The family remained locked indoors for two days while stuffing all their pillows and blankets on the windows. They only briefly ventured outside to see to their bathroom needs and to feed their animals by bolting back and forth. Savvying their lack of security, however, they left off for downtown, leaving their animals behind.

Zübeyde Turan from the Yukarı Yiğitler village was one those who ran away from the village with her family as soon as the bombs began dropping; so much so that they did not even take any extra clothes with them.

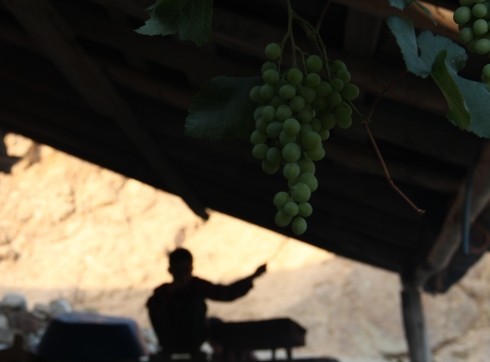

"You ought to have seen our vineyards and gardens; they were so pretty," 85 year old Ahmet Kaplan sighs, dropping the conversation there.

Thousands of dead trouts

Nevzat Çiftçi from Bağlar village is the only one running a trout fishery in the area. He arrived in the downtown area to purchase feed for his fish, but the gendarmerie did not allow him back into his village.

Once he did arrive back in his village, however, he found out that thousands of his fish were dead. The damage he has incurred totals nearly 100,000 Turkish Liras. He is back in downtown but cannot return.

Şemdinli locals' principal mainstays are beekeeping, grapes, tobacco, walnuts and a bit of animal husbandry. Everyone commended the "Karakovan honey" and lauded it for being on par with the Anzer honey; I was unaware of it.

They also commend the "zozan" (highlands) and the Cilo mountain range that features glacial mounds and lakes.

Nature on the line

It is high time now for vine harvest and honey gathering, but neither the bees that have flown away nor the vineyards and forests set ablaze by the conflict have any more fruit to bear.

As the conflict continues to exact a hefty toll on nature, laying waste to fertile land and wreaking havoc on locals' livelihood, the Hakkari-based Culi Nature Association has also arrived in Şemdinli to assess the situation.

Claims regarding the use of "chemical weapons" and "phosphorus bombs" has seriously unnerved everyone, according to Mesut Kıratlı, the head of the association.

If those claims are founded, then no one will dare to eat off the remaining grapes, he said, adding that it would present further "dangers" to keep planting crops on the soil, too.

Many international institutions paid visits to Hakkari to explore the uncharted plant flora and the countless species of animals in Şemdinli, but officials denied them access due to the fact that it is a forbidden zone, according to Kıratlı.

The natural landscape of Şemdinli is thus still incognito due to this reason, he complained.

The mountain across

I lend my ear to the youngsters whose peers, relatives and friends are now roaming the mountain across.

All schools are located in an area next to the gendarmerie post, including the high schools. A mortar shell even landed inside the school yard last year, they say.

They also complain of overcrowded classrooms and the fact that their teachers change about four times a year, as the teachers have difficulty bearing the circumstances in Şemdinli, which still lacks a single movietheater.

Their greatest source of bitterness, however, lies in the discrimination they face. A group of students from the school travelled to Istanbul to watch a match in the company of the police, but the two rows where they sat were entirely cleared off of all other spectators.

"Why are they so afraid of us? Can we not watch a match together?" they ask.

They want to become engineers, doctors and teachers, if circumstances allow for it, but it is the "mountain across" their conversations keep floating back to. (NV)