On 14 May, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reached Soma, the site of the coal mine explosion that has so far killed 321 people—an already horrific number feared to surpass 350. In his first public appearance, twenty-four hours after the explosion, he seemed sultanically informed about the dates of previous coal mine explosions and their resultant deaths, not only in contemporary Turkey, but also across time and space. After having thanked the media “workers” for their “responsible” coverage of the calamity or catastrophe (facia in Turkish) as an unfortunate yet ordinary “work accident,” Erdoğan was ready to present some facts on the ground for all. Beginning with a warning against “marginal groups who are trying to make use of this accident” for their political ends, Erdoğan lectured on:

I want to share with you some numbers to put things in perspective here. Between 1942 and the end of 2010, friends, our total number of deaths in this type of accidents is around 900. 42, 47, 55, 83, 87, 90, 95, 2010. Among these the methane gas explosion experienced in Kozlu in 1992 has been recorded as the biggest accident that cost 263 workers their lives. This is what it is with coal…Let us remember the past in England: in 1866, 362 people were reported dead. Another explosion in England in 1894, 290. Let me move to France: 1906, the second deadliest mine accident ever recorded. Let me move to more recent periods: Japan in 1914, 687. China, in 1960 gas explosion in the mine, 684. And from Japan, again coal explosion again in 1963, 458. India, 375. In 1975, gas catches fire again, and the roof of the mine collapses and 372. At this point these kinds of accidents are ordinary and recurrent things in these mines…Take a look at America, with its technology and all, in 1907 361 people…These are recurrent and ordinary things. In literature they are referred to as work accidents.

Erdoğan’s anachronistic collage of nineteenth-century Britain, late-twentieth-century India, and many other places and times in between as the explanatory grounds to rationalize coal mine explosions as unfortunate but ordinary parts of the business of mining is itself not only unfortunate, but simply despicable: void of thoughtful and grounded zikr (remembrance; invocation), before we can even get to fitr (genesis; constitution) to put it differently. What Erdoğan’s interview reveals is less the characteristics of the coal mining and extractive industries under the ordinary business of capitalism, and more the very fitrat of the Erdoğan administration’s “corporate-state” itself per Bulent Kucuk’s formulation, and its ways of doing capitalism in Turkey. More directly, what is revealed in Soma is the fitrat of the contract-based companies that blatantly perpetuate working conditions that keep workers on the brink of a potential or real massacre in the extractive as well as in the construction industries in Turkey. As the people of Soma and those protesting in solidarity with them have repeatedly underscored, the death of more than 321 people in a mine does not constitute a work accident, but a massacre that was committed by concrete actors. They now need to be held accountable.

This “Labor Massacre,” and not “work accident,” illustrates the deadly and despicable effects of the “high pace of development” enshrined in the fitrat of Erdoğan’s corporate-state. Further, it reflects how that “development” produces and depends upon a variety of disasters in the cities and the hinterland. The Soma Massacre is not a calamity that has befallen the Soma miners, but a massacre committed against an entire town under the increasingly reckless and callous subcontractor (taseron) capitalism of Erdoğan’s “corporate-state.” Among the elements that constitute the particularity of the Erdoğan form is that the disposability of these particular bodies, all 321 of them and counting, is expected to be cloaked over in a language of takdir-i ilahi (divine predestination) and fitrat (genesis).

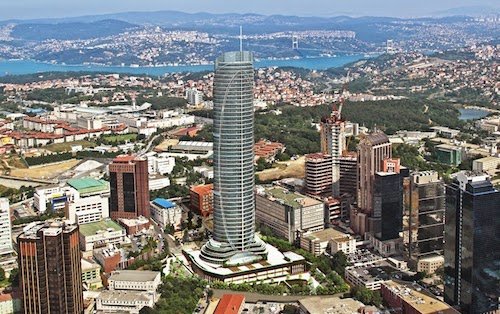

The particular form that capitalist destruction takes under Erdoğan—and the scale and pace of the plunder economy it forms and performs—is reflected in the connections between the depths of the Soma mine and the heights of the Spine Tower, the luxury residence tower that looms imposingly over Istanbul’s Little Dubai in Maslak (Image). The Soma Group that “rents” the coal mine in Soma also happens to be the force behind the “Spine Tower.” With luxury flats for sale starting at 3.4 million USD in the Tower, the Soma Group has registered a 250 percent increase in production over the course of the last six months alone. At the same time, construction workers were faced with lowered wages, deteriorating working conditions, and a complete lack of emergency safety infrastructure in Soma. As a short article on Diken has put it: the cost of twenty safety rooms to ensure the possibility of evacuation for up to eight hundred miners in Soma would have been the equivalent of the cumulative price of four of these luxury flats in Maslak. This fact alone is maddening enough in the aftermath of the Soma Massacre to inspire a mass movement demanding that the Soma Group and its state-level beneficiaries be brought to justice and held accountable for the man-made catastrophe they have wrought.

This is not an attempt to “explain this murder based on Erdoğan’s personality and the authoritarianism of his circle,” which Cihan Tugal has recently flagged as a predictable trope of analysis in contradistinction to more historically informed, if not crudely Marxian, political economic approaches to late capitalism in Turkey. Nor am I interested in “paying lip service to ‘neoliberalism's’ destructiveness” first, only to make a culturalist argument second. That said, I do maintain that the historically and socially particular form that late capitalist destruction has taken under Erdoğan’s regime has to be addressed in conjunction with his administration’s concrete actions and actors. In other words, the particularity of this case has to be thought through.

In parsing this particularity, I want to suggest that the particular form of Erdoğan’s corporate-state is predicated upon a conglomeration of speculative, constructive, and extractive capitalists (and the objective of its shareholders to cloak their atrocities with a superficial blanket of tasavvuf / تَصَوُّف [mysticism]) that has to be studied in its own right quite apart from analyses focused on “liberal-conservative agendas,” as, again, Tugal put it. Indeed, in the location par excellence of taseron capitalism, the supermarket, the effort to cloak atrocity in a mantle of mystical predestination has been shredded to pieces before the cameras in Soma, with Erdoğan and his aide powerless to reclaim the narrative. This uncloaking might well explain the kicks and slaps swung at Soma’s people by Erdoğan’s entourage even as that community reeled from the massacre visited upon it by the administration’s extractive coterie, who by commission and omission paved the way for the complete destruction of the social ecology of Soma.

This corporate-state is not a signatory to the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) declaration number 176 on “Safety and Health in Mines,” signed with the endorsement of twenty-six countries in 1995. Not only in mines, but also in other industries, the number of workers’ death in Turkey is alarmingly high: according to the numbers reported by the ILO and disseminated through the Istanbul Branch of Turkey’s Chamber of Civic and Cartographic Engineers, Turkey ranks as number one in work-related accidents in Europe. Every day in Turkey, 172 work accidents take place, whereby three workers lose their lives and five others are rendered permanently debilitated and/or disabled. According to a recent Bianet article reporting on this data set, between the years of 2000 and 2012 alone, 12,686 workers lost their lives due to work accidents in Turkey. The ILO data suggests that these numbers are surpassed only by those reported in El Salvador and Algeria. Every year, in other words, approximately 1,100 workers lose their lives in Turkey as a direct consequence of under-regulation. The highest proportion of these deaths, accounting for one-third of all work accidents reported, comes from the construction industry. Transportation, mining, and metal production follow closely behind in the killing and maiming of workers in preventable “work accidents.”

“42, 47, 55, 83, 87, 90, 95, 2010…” Erdoğan seemed to be unfortunately misinformed about some other numbers on the ground, those that reflect the fact that Turkey’s twenty-first-century performance in occupational safety stands on a par with the nineteenth-century performance of its neighbors. Of course, his failure to appreciate what these numbers truly reflect might be a consequence of the fact that the aides that feed him his facts were otherwise occupied that day. They were kicking the family members of those killed in Soma in front of the municipal building before dozens of cameras, as was the case with the prime minister’s aide, Yusuf Yerkel. In fact, this despicable act on the part of a state official embodies the violent anxiety around the disaster and what it might reveal about the concrete actors involved. The operations of the Soma Group’s mining company is an extension of the Erdoğan corporate-state, which has overseen privatization schemes around coal mining and construction, creating unregulated industries that sacrifice occupational safety and labor protections in favor of profits.[1]

If one defining feature of Erdoğan’s corporate-state is the sheer pace of the capitalization of land and resources from Maslak to Soma, another is the effort to shield the disastrous effects of this process from scrutiny by appealing to popular conceptions of fate, destiny, and inevitability. From Roboski to Soma, Gezi to Reyhanli, the Erdoğan administration’s list of atrocities re-described as passive calamities that befall the nation keeps growing. The “operational mistakes” of Roboski and “work accidents” of Soma and the urban transformation of places like Gezi in Istanbul are in fact more connected materially than we think. This narrative of predestined catastrophe continues to facilitate impunity for perpetrators and injustice for victims. The political utility of subcontracting is especially evident when Erdoğan appeals to mystical explanations for state failure—that is, thetaseron work done by the appeal to tasavvuf terms by Erdoğan communicates to Turkey’s citizenry a progress narrative that naturalizes the wounds inflicted by the corporate state and turns them into inevitable collateral damages or scars of economic progress. When faced squarely with accountability for the working conditions of miners and the failure to provide for basic protections and regulation, the transformation of the issue into the language of accident and the fitrat of the miners’ condition ensures not only that the state will not be held accountable for its failings, but that state responsibility for corporate commission and omission will remain shielded from view.

Given that the state-issued price of coal, on which the state depends for twenty percent of its electricity production, is fixed and not open to speculative competition, one does not need to be a rocket scientist to understand the source of the Soma Group’s surplus value and grounds of speculation. In other words, to say that the Spine Tower is built and rises to its imposing Istanbul skyline position in Maslak on the bodies of those who were literally worked to death in Soma is unfortunately not a metaphor. The Soma Massacre reveals the mutually constitutive link between the urban transformation of Istanbul under AKP municipal and national governance and the privatized coal mining industries in Western Anatolia, particularly after the 2005 reforms. Even this very brief sketch of Soma Holding’s corporate structure shows its position in the broader architecture of Erdoğan’s corporate-state and the atrocities for which it is directly responsible. To that list we may now add the biggest coal mine massacre in the modern history of Turkey.

NOTES

I am grateful for the generous feedback I have received from Anthony Alessandrini, Aslı Bâli, Naor Ben-Yehoyada, and Anand Vaidya on earlier drafts of this piece. All errors remain my responsibility.

[1] The connections are cemented through rodovans (a method of payment in coal to the state that effectively operates as a currency to refinance construction projects and “diversify” business ventures on the part of entrepreneurs). For a more detailed and quantitatively oriented account of the triangulation between the Soma mine, the Spine Tower, and the state privatization program and transformations of mining under Erdoğan’s privatization schemes after 2005, please see Umit Akcay’s work in Turkish here.

[2] See the infographic from The Times, 14 May 2014, accessed through Twitter. Numbers of the deceased and the rescued have since changed.

* This article has been republished from Jadaliyya.