The year 2025 has been recorded as one of the most severe droughts in the past 65 years for Turkey.

According to data from the General Directorate of Meteorology (MGM), between Oct 1, 2024 and Aug 31, 2025, the country received an average of 401.1 kilograms of precipitation per square meter. This amount was 27% below the water year average of 548.5 kilograms, and 29% lower than the 563.2 kilograms recorded during the same period last year.

Precipitation levels were particularly low in Central Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia, and Thrace, where rainfall fell 40% to 60% below long-term averages.

Evaporation driven by the climate crisis, along with declining rainfall, has significantly reduced water levels in lakes and reservoirs in Turkey and around the world. In a paradoxical contrast to the climate crisis “disaster,” this situation has been “promising” from a cultural heritage perspective, revealing ancient structures that had been submerged for centuries.

These newly visible historical structures offer a glimpse into the depths of history, while ancient roads, sunken villages, and submerged buildings exposed by drought serve as stark reminders of how the climate crisis threatens our lives.

Examples from Turkey

Along the shores of Lake Van, water has receded by nearly two kilometers in some areas in recent years. In 2022, due to drought, a port from the Urartian period, an open-air worship site, a rock-carved pier, and sarcophagi etched into the bedrock were revealed. Scientists who examined the site noted the historical significance of the T-shaped sacred worship areas.

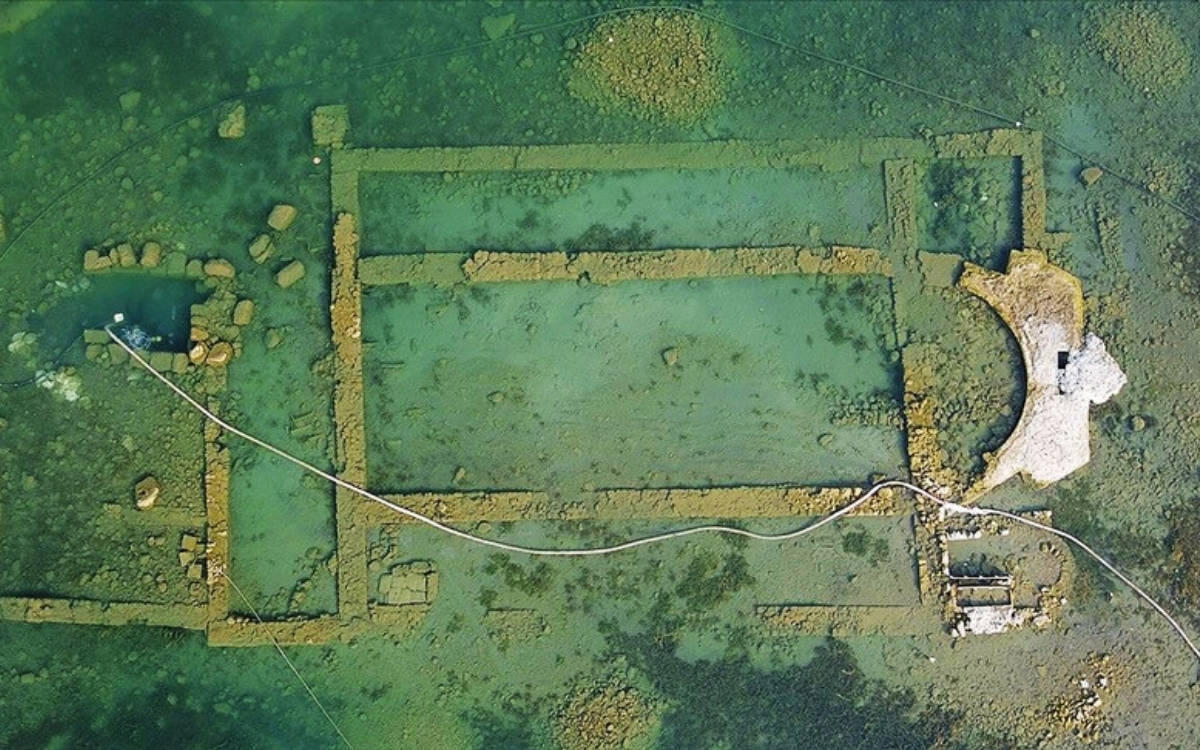

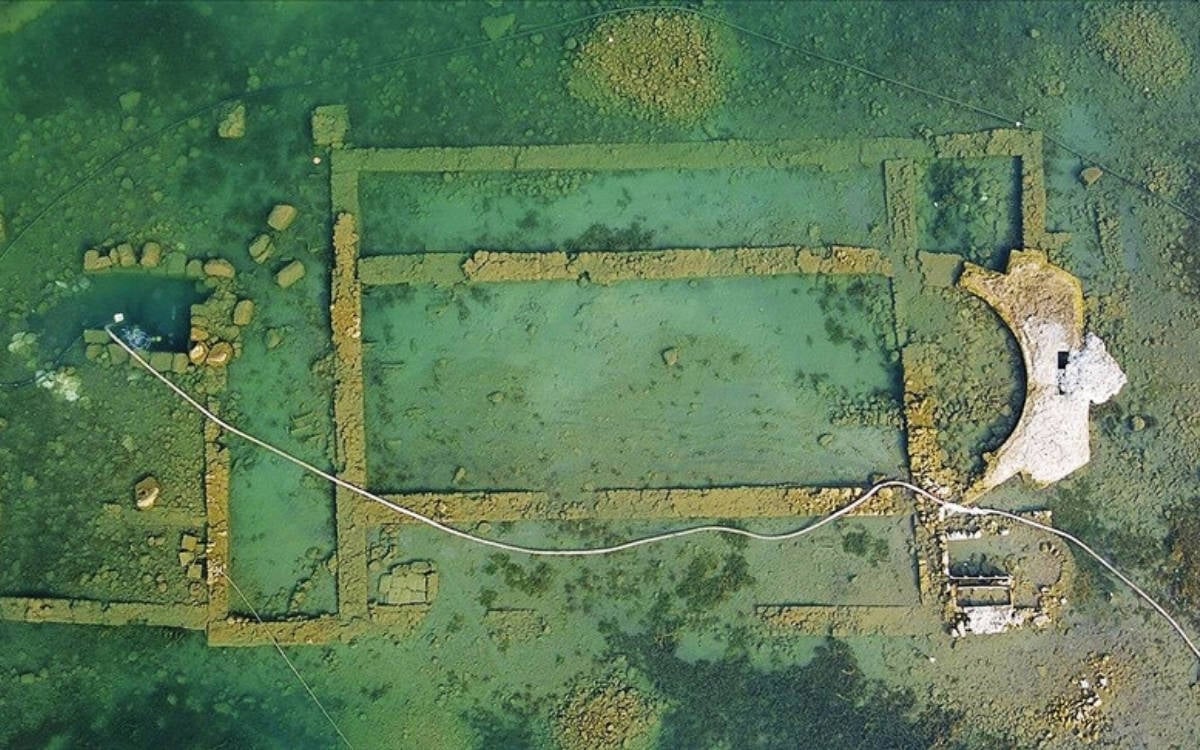

A similar event occurred at Lake İznik, the largest natural lake in the Marmara region. Water levels dropped by up to 50 meters, causing a large portion of a basilica built around 1,500 years ago in honor of Saint Neophytos to emerge above the surface and connect with the shoreline. Some experts say this presents new “opportunities” for the preservation and promotion of the site, which is planned to be turned into an underwater archaeology museum.

In the Atatürk Dam in the Samsat district of Adıyaman, receding water levels exposed a Roman-era settlement and historical artifacts in Nov 2022. Discovered by local fishermen, the structures were examined by teams from the Adıyaman Museum Directorate, who found tombs, broken pottery, a historical axe, and other cutting tools.

photo: In Erciş district of Van, an 11-step ancient harbor was revealed below a Urartian-era castle as lake waters receded.

'No cause for celebration, it’s the result of a major natural disaster'

The emergence of ancient structures due to drought and receding water levels is, of course, not unique to Turkey. Some notable examples from around the world include:

- Spain – Sau Reservoir: The 11th-century Church of Sant Romà de Sau, submerged in 1963, reappeared as water levels dropped.

- Spain – Aceredo Village and Andalusia: Remains of submerged villages have resurfaced during droughts. Similar situations have been observed in Portomarín (Lugo), Bande (Ourense), Cantabria, Navarra, and Extremadura.

- Italy – Lake Garda: The retreating waters have made it possible to walk on foot to San Biagio Island.

- Greece – Mornos Reservoir and Kallio Village: The remains of a village submerged in the 1970s became visible again due to the 2024 drought.

Meanwhile, in the village of Prahovo in eastern Serbia, the receding waters of the Danube revealed the remains of a Nazi German warship from World War II in Sep 2024. Despite its rusted exterior, the hull of the ship remains largely intact.

While domestic and international tourists have flocked to see these structures, some officials have expressed discomfort with the idea of “drought tourism.” For example, Joan Riera, the mayor of Vilanova de Sau, stated, “There’s nothing to celebrate about tourists coming here, because this is the result of a natural disaster that has severely impacted our region.”

How will the revealed structures be preserved?

Museum curator and ancient historian Gülşah Akın, evaluating the ancient structures exposed by drought caused by the climate crisis and how to protect them, said she found their emergence to be a positive development but emphasized that the fact they were revealed due to the climate crisis is concerning:

“Similar developments have occurred throughout human history. During periods like the interglacial ages, many communities relocated. For instance, at Yeşilova Mound in İzmir, three different settlements were established in very close proximity due to natural disasters. In ancient times, major droughts and other natural factors led to the collapse of civilizations, and we have long observed the effects of climate conditions on societies, and we continue to do so. The structures we see today are part of that historical continuity. The difference is that, in the past, such changes unfolded over millennia, or at least centuries; now, they’re occurring much more rapidly, in just a few decades. Yes, these events happened before, but in terms of today’s pace and global scale, we are in a different era. So yes, it’s a positive thing that these structures are surfacing; but it’s worrying that the reason behind it is the climate crisis.

“Moreover, preserving the newly revealed structures is another matter entirely. Whether they should be preserved in situ or moved to museums is a topic of debate. Organizations like UNESCO generally recommend preservation on-site, since it’s important not to remove the structures from their historical context. But this also requires significant resources, security, and technical measures. Just like artifacts from the ancient cities of Ephesus or Aphrodisias are preserved in museums, the structures exposed by drought must also be protected. The artifacts from Ephesus and Aphrodisias were removed from their original locations and are kept in controlled environments, protected from both physical and climatic impacts. But now, for example, it remains unclear how the ancient road that resurfaced in Van will be protected. Still, I believe that, as in the rest of the world, scholars in Turkey will make every effort to ensure the careful preservation of these structures.”

'If preservation measures are not taken, these assets will soon disappear'

Archaeologist Gül Yurun Mavinil emphasized that while these areas revealed by drought may seem like new tourist destinations under the label of “drought tourism,” it is unrealistic to expect them to remain sustainable for long-term visits. She continued:

“The effects of the climate crisis are no longer just a prediction about the future, they are a reality we are living today. Cultural assets emerging from beneath dried-up lakes may initially appear to offer new opportunities for ‘drought tourism.’ However, it is not realistic to think these sites can be sustainably visited for long periods. Archaeological remains suddenly exposed to semi-arid or dry conditions after existing in a highly humid environment are vulnerable to rapid physical and chemical degradation. Without proper preservation measures, these assets will quickly deteriorate.

“At this point, we need to ask ourselves: Should we view cultural assets solely through the lens of tourism? In fact, they represent the memory of the geography we inhabit. What lessons can this memory teach us from past to present? If we fail to take preservation measures today, are we not infringing upon the rights of future generations? The structures surfacing from beneath dried lakes remind us not only of ancient civilizations, but also of today’s environmental crises. These lakes are essentially indicators of the freshwater we’ve lost. This situation also clearly signals the water crises we are likely to face in the future.

“I completed my undergraduate studies in archaeology and geography, and my master’s in geography. The intersection of these two disciplines—paleogeography and geoarchaeology—enables us to understand the geographical conditions of the past. Evaluating a society solely based on today’s circumstances can mislead archaeologists. That’s why knowing the climatic and environmental conditions of a given period is critically important. With this perspective, we can observe how societies in the past built resilience to droughts, natural disasters, and climate shifts. These insights may help us develop local solutions to today’s climate crisis.”

'Cultural heritage becomes the easiest target during extraordinary times'

While climate change is a global issue, Mavinil noted that local communities will respond in ways shaped by their unique circumstances. She concluded her remarks as follows:

“Though climate change is a global matter, the responses of local communities will be shaped by their own ways of coping with local challenges. In Turkey’s case, the issue is multi-dimensional. It is essential to identify how each region is vulnerable to climate change and to develop corresponding action plans. Heritage sites are particularly fragile in the face of rising temperatures, extreme rainfall, floods, storms, and shifting wind patterns. This vulnerability does not stem from nature alone. During extraordinary times, cultural heritage becomes one of the easiest targets. Today, climate activists are staging protests by targeting artifacts displayed in museums. Why is cultural heritage the target? Even if the aim isn’t to cause significant damage, we must consider the perception such acts create in society.

“Another dimension of climate change is its potential to trigger periods of social turmoil. Let me cite some examples from the past. After the February 2023 earthquake, there were social media rumors about possible looting of archaeology museums, which sparked public concern. During the Syrian war, ISIS filmed and bombed ancient cities to draw global attention. In the Iraq war, the Baghdad Museum was looted. These cases show us that, regardless of a society’s level of prosperity, in times of crisis, people can revert to primal instincts and cultural heritage is often among the first to suffer.”

What is drought tourism?

Submerged villages, underwater historical structures, ancient roads, and islands resurfacing due to drought have given rise to a new phenomenon known as “drought tourism.”

The term refers to the act of visiting historical, cultural, and natural sites that reemerge as water levels drop due to drought. However, turning these areas—revealed as a result of climate disasters—into tourist attractions raises serious ethical concerns.

Experts warn that drought tourism may harm natural areas and local ecosystems. High tourist traffic could disrupt ecological balance in some regions and negatively affect local communities.

Professors Kaitano Dube and Godwell Nhamo, in their studies particularly focusing on the Cape Town Day Zero experience, highlight how drought can push the tourism sector into a state of crisis and significantly alter the tourism image of affected regions. Their research underscores that drought tourism poses risks not only to cultural heritage and the natural environment but also in terms of social justice and sustainability.

If the newly revealed structures are not protected, they may erode under tourist impact. Stones could be removed or damaged by graffiti, leading to further deterioration.

Sources: Associated Press, AFP, Water Issues, Anadolu Agency, Mezopotamya Agency.