It has been three years since the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan on August 15, 2021. Since then, it has issued at least 85 decrees restricting the rights and freedoms of girls and women.

For example, women are banned from university and high school education.

Girls' middle and high school education has been suspended, and they are only allowed to study up to primary school level.

Women were also banned from traveling more than 72 kilometers without a male companion.

Of course, this is only the “written” part of the life the Taliban deems “appropriate” for women. Women in Afghanistan also have to suffer dozens of unwritten bans.

In other words, since the Taliban take-over, women in Afghanistan have woken up to bans every day.

While women in Afghanistan are deprived of their rights and dreams, organized women in Turkey strive to give voice to Afghan women’s voices and struggles. One of these groups is the Women’s Platform for Equality (EŞİK). I interviewed one of its members, Dr. Özlem Altıok, who is also a faculty member at the University of North Texas.

Altıok, who teaches in the departments of Women's and Gender Studies and International Studies, told Bianet about the impact of the Taliban on the lives of women and girls in Afghanistan: “Afghanistan is a kind of political mirror for women in Turkey, not an imaginary mirror, but a mirror in thought – a mirror showing us a possible future, not an imaginary one, and certainly not one of our imagining...”

'The Taliban punishes men too when women violate bans'

What have been the most significant changes in the rights of women and girls since the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan?

The 40 years of cold and hot wars waged by imperialist powers in Afghanistan, as well as the ongoing civil wars, make life in Afghanistan very difficult for men and women, for almost every ethnic group. Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries in the world.

This has a negative impact on the whole population, of course, but because of the existing gender inequalities and the misogynist policies of the Taliban, women feel the burden of poverty the most and the deepest. They feel it in their bodies.

Since coming to power, the Taliban has issued at least 85 decrees restricting the rights and freedoms of girls and women. These do not just remain on paper, either. The Taliban also places the responsibility for enforcing the prohibitions on male citizens as well, punishing the men in their families if women violate them, obliging them to enforce the Taliban’s bans.

'Gender apartheid'

What do you think about the exclusion of women and girls from public and political life, according to reports by the United Nations and independent organizations?

The Taliban excludes women and girls from social and political life, and they do it so systematically that it has its own name: gender apartheid. “Apartheid” is an Afrikaans term, it is difficult to translate into Turkish and that's why I use it in English. Because it also serves as a reminder of the historical circumstances from which the term emerged...

I can explain it as the separation of the spheres of life of men and women based on “traditional” gender presuppositions, norms and roles, usually based on a strict and patriarchal interpretation of religion by the state/government. Different spaces for different genders - not just different, but unequal, where men (and the masculine) are valued, at the top and the decision-makers.

Just as in apartheid South Africa until the 1990s where whites ruled the black population and strictly separated their neighborhoods from those of the blacks in every way including infrastructural, cultural and resource distribution, today in Afghanistan, the all-male Taliban sees the right of men to rule women as “natural” or “Islamic”.

Moreover, it isolates women from public spaces; it imprisons them in the home. Considering the restrictions on freedom of movement, “prison” here is hardly a metaphor.

The separation of spaces between men and women is as absurd and unacceptable as the separation of public spaces based on race. While gender apartheid is not a crime in international law, gender persecution is. And there is an ongoing investigation against the Taliban for committing gender persecution, a crime against humanity under international law.

I understand that a legal investigation has its own dynamics, the need for evidence, etc., but in a sociological sense, I think there is plenty of data on what is going on in Afghanistan, and not much left to investigate. On the other hand, there is an international campaign supported by women's organizations in Turkey and around the world that calls for the recognition of gender apartheid as a crime against humanity.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Afghanistan recently published an important report (in May of 2024), which increased the visibility of this demand. (The Women's Platform for Equality also supported the gender apartheid campaign in solidarity with international women's organizations; followed Mr. Feridun Sinirlioğlu's independent assessment of the situation in Afghanistan for the UN Security Council; and sent him two letters last year).

'Women are not allowed to receive health care without a male guardian'

What do you think about the Taliban’s decision to ban girls from going to school from 6th grade onwards? What are the implications of this decision?

In the three years since the Taliban came back to power, women and girls have been stripped of their most basic human rights.

They have been denied the right to post-primary education and the right to work. Right now girls cannot go to school. The Taliban said they would open schools in accordance with Sharia law, but they haven't done that either. Education for girls is certainly not a priority. In fact, the Taliban's ideal life for them is to stay at home, serve their families, and obey and serve as slaves to the men in their families.

Women in Afghanistan must wear clothing that covers all parts of the body (except the eyes). Women are forbidden to travel more than 72 kilometers from their homes without a male escort. Their freedom of movement/travel is severely restricted. They are not allowed to go from one place to another, even to a park or hospital, without a male companion, and they are not allowed to receive health services.

According to a decree issued by the Taliban in January 2023, female health workers are expected to go to work with a male companion from their “mahram” (male members of their close family).

'Talibanization in Turkey'

How does depriving women of education affect the future of Afghanistan's society?

Societies without education are doomed to decay and collapse; it is not possible for them to break out of the spiral of violence and become productive and hopeful.

Armed and unarmed reactionary “Islamic” networks/organizations (cemaat), whose mentality is similar to that of the Taliban and which have been nurtured and encouraged for years in our country and in many countries in our region, generally want everyone, men and women, to remain uneducated. In fact, they want them to receive and understand even religious knowledge in a single, dogmatic way. As it suits them! In other words, blows to education make their job easier. Because it is difficult to rule an educated people with prohibitions; it is difficult to put them to sleep with religion or superstition.

Let us remember the constitutional amendments that the AKP brought to the agenda in December 2022 and attempted to pass through the Turkish Grand National Assembly. In that context, I had written an article on talibanization in Turkey. B Talibanization, I am referring to the growing influence of congregations, foundations and armed/unarmed groups that control areas and/or spaces outside the state's control (or that the state chooses not to control) and govern them based on religion (more specifically, on this or that influential religious leader’s interpretation of Islam).

I had also argued in that article that we should focus not really on whether the Taliban's bans on education are really in accordance with Islam as interpreted by this or that person, but rather the fact that societies that do not uphold the principles of equality and secularism will not do well).

The Taliban may be a reality specific to Afghanistan, but we observe talibanization as a process, and its concrete effects in Turkey today.

Principals of schools that are administered by Turkey’s Ministry of National Education are forcing female students to cover their heads, in violation of existing codes and regulations. In some cities, and not just in small ones, female students have not been allowed to attend the graduation celebrations of the schools they have worked so hard to complete on the grounds that they were dressed “inappropriately.”

Going back to the issue of Taliban's prohibitions: If girls and women remain uneducated, if they do not know that there is another way of life, another world, it is easier to control them. In the globalized world, in the age of the internet, social media, smartphones, one might think that this is very difficult. And in a sense, it is.

However, not being able to go to school also means not being able to see other lives; it means not having access to novels; it means being deprived of opportunities to broaden your horizons; it means not being able to discuss menstruation, sexuality or an early marriage proposal/arrangement with your friends or teacher; it also means not being able to play sports.

'Banning civil society'

What impact does the exclusion of women from the world of work have on their economic independence and overall well-being?

The exclusion of women from the labor force undermines their economic independence and has a negative impact on their well-being, and it has had precisely this impact on Afghan women. However, the problem is even bigger than that.

After the Taliban came to power, they sent women employed in the public sector, women in news organizations home.

They also banned civil society work. We can say that Afghanistan was “governed” for decades due to international and local civil society organizations. Since the mechanism called the state, the services expected from the state, etc. did not / does not really exist...

At least in the cities, these organizations provided most of the employment, especially women's employment. Thousands of women lost their jobs and tens of thousands of women lost the jobs they had hoped to get when the Taliban told United Nations agencies that “hiring women is forbidden” ...

In Afghanistan, which has been impoverished by wars and devastation, where much of the male population has died in wars or migrated to neighboring countries, it should not be forgotten that most of these women are the sole breadwinners for their families and homes. It may be easy for some people to say that “men should get jobs and provide for their families; women should take care of the house and children”, but this does not correspond to the realities of life (not in Afghanistan nor in other countries).

'Afghanistan is a kind of political mirror for women in Turkey'

What do you think about the abolition of laws and institutions that were previously put in place for the elimination of violence against women under Taliban rule?

By closing domestic violence shelters and abolishing laws and mechanisms that were instituted to prevent violence and protect survivors – laws and institutions which in reality were already weak for a number of reasons, not to mention in implementation – and by abolishing the institutions where survivors of violence could go, the Taliban basically sent a message to women: Your life, your health and your children's lives are in the hands of men. You will stay at home no matter what. Are you being abused? Obey better. Your family, your home is the best place for you. I do not think I am exaggerating or adding a wrong interpretation.

The reason that feminists in Turkey follow what is going on in Afghanistan (and Iran) so closely is that in the violations of women’s most fundamental rights in these countries (always justified by reference to religion), women see their own possible future (which women do not desire but some are planning for us anyway). Looking at Afghan women’s plight, we are looking at a kind of political mirror, a mirror showing us a possible future, not an imaginary one, and certainly not one of our imagining...

The Women's Platform for Equality, Turkey pointed to this very point in its press release immediately after the Taliban came back to power in August of 2021:

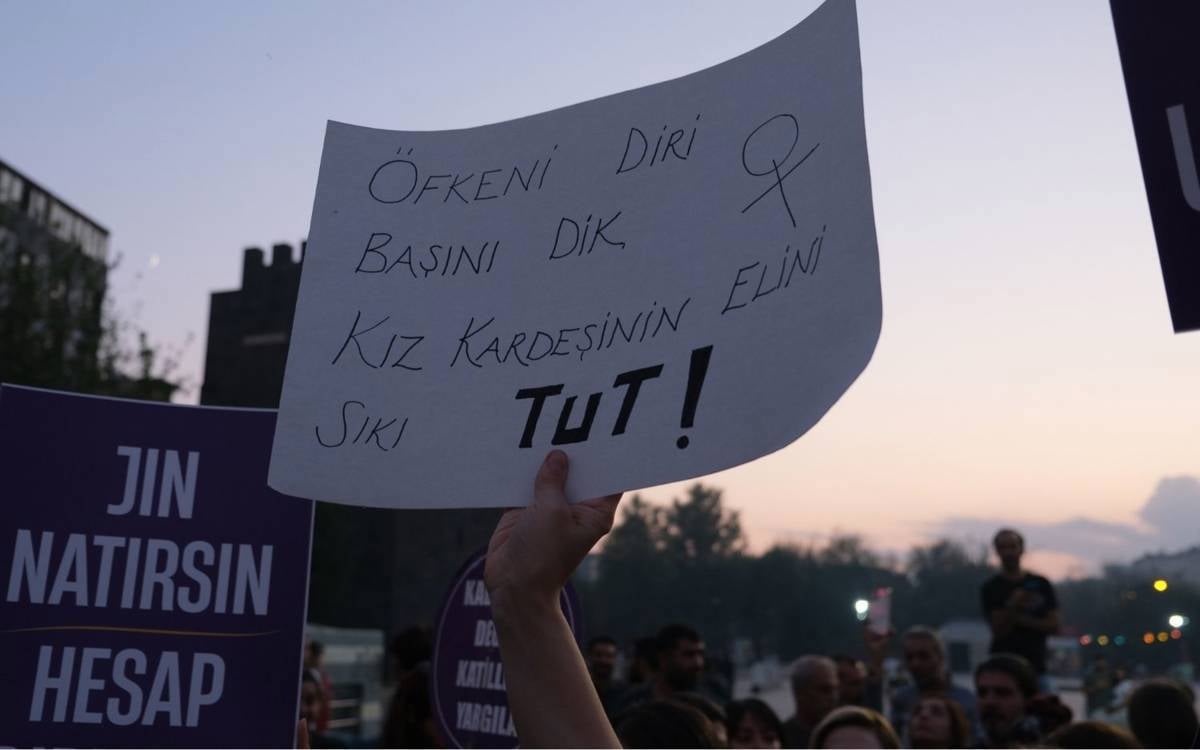

“We are aware that the struggle to be waged together with the women of Afghanistan is part of the struggle against those who ignore the Istanbul Convention, those who talk about skirt length, and misogynists who reject gender equality. We look at our common future in the mirror of what Afghan women are going through. We call on all women and opposition forces to unite their struggle as soon as possible.”

Afghanistan and Turkey are two countries with very different political histories and cultures; of course they are different. However, let's not forget that the Taliban mentality has its extensions in Turkey, too and thanks to those ruling Turkey, issues that we could not have imagined 10-20 years ago are now being open to debate.

In Turkey, the mentality that labels the Istanbul Convention as “destroying the family” and attacks Law No. 6284 and women's right to alimony is fed by the same argument; it desires the same thing. It draws from deeply patriarchal and misogynist interpretations of Islam has a patriarchal interpretation and wants to make men the masters of women.

Likewise, the fact that Iranian women, and Women Living under Muslim Laws more generally, are closely following what is happening in Afghanistan and demanding that gender apartheid be recognized as a crime under international law can be explained as much by the loss of rights (or current risks of loss of rights) experienced by women in Iran as by international feminist solidarity.

How does the lack of legal and social protection mechanisms for women in Afghanistan affect their lives?

I don't know if there is a need to state this explicitly, but violence against women is very prevalent, both in Afghanistan, Turkey and other countries. This is because we have not yet transformed patriarchal societies in a feminist and egalitarian way.

When we do, everyone will live better lives! As feminists, we have a dream of a beautiful, prosperous society in harmony with nature, where we will need less mechanisms to prevent violence and protect victims, and where women, men, or people who identify themselves outside of this binary gender system will also live safer lives!

Unfortunately, we are not there yet; we still have a long way to go. The current dismantling of institutions with a mandate to prevent violence against women or to provide protection and services to victims of violence has dire consequences for women.

It means that women have nowhere to go when their basic human rights – the right to life, the right to health – are violated! It means confining women to abusive and violent family relationships and the home.

How do you assess the current situation regarding child and forced marriages?

Let me start with a few findings that have sociological validity. We know from many studies conducted in different countries that low levels of education are associated with early, forced and child marriages. Poverty is also directly related to lack of education and early marriage. This is also the case in Afghanistan. Of course, the special case in Afghanistan is the Taliban, who are adopting policies to actively and deliberately undermine girls' and women's education and employment opportunities.

Let me say a few words about poverty. The economic situation for women in Afghanistan - and for the Afghan people in general - is bad.

There are many reports showing how deep poverty is. In addition to the World Bank and UN Development Program assessments of Afghanistan in 2023, the World Food Program report in 2024 also shows the extent and depth of poverty in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is one of the most impoverished countries in the world in terms of Gross National Product (GNP) per capita. Drought is a major problem in Afghanistan, which is also directly and seriously affected by climate change and global warming. Nearly 16 million people out of a population of 40 million are experiencing crisis-level food insecurity. Add to this the damage and loss of life caused by the earthquakes in Herat last October, about 8 months after the earthquakes that hit Turkey and northern Syria…

Let me open a parenthesis and say this: Afghanistan's economy depends on agriculture. If we consider that the drought caused by climate change as a natural disaster that deepens poverty (although we know that climate change and drought are results of human activities, and are not only “natural”), we can better appreciate how Afghanistan is experiencing both political and natural disasters, and how women are squeezed in this bind.

In an environment where women's movement is restricted and their rights to education and work are usurped, it is women and their dependent children who are most affected by poverty, unemployment and hunger...

The Taliban's ban on women from education, work and public life in general means that girls are at a much higher risk of finding themselves in early and forced marriages.

I should also note that early marriage can be seen (by families) as a security measure in times of war and other armed conflicts. Therefore, the struggle to end wars – all of them – is a feminist issue and should always be on the agenda of feminists.

What are girls and women who cannot get an education, who are forbidden to work outside in paid employment, to do in an environment of deep poverty? Families already struggling to take care of them may see marriage as a means of providing both economic and physical security.

According to the UN Development Program (UNDP) report on Afghanistan in 2023, many households in Afghanistan try to make ends meet by selling land, houses and other income-generating assets. The same report also states that commodification of family members is among the strategies that households use to cope with poverty. We are talking about selling the labor force of boys and the girls themselves (as brides).

Other news and reports from Afghanistan also show how bad the situation is, but that it does not affect everyone in the same way and to the same degree. Poverty and Taliban restrictions are bad for everyone, of course, but most of all for girls and women, and ethnic minorities, including the Hazara people.

The health crisis facing girls and women in Afghanistan is evident from the report of DROPs, a think tank formerly based in Afghanistan (now in Canada), has published a shadow report following the independent assessment report prepared by Feridun Sinirlioğlu who was tasked with providing an independent assessment of the situation in Afghanistan.

DROPS’ report is also a response to the fact that the independent assessment report that was submitted to the Security Council in late 2023, and which did not adequately address the systematic violations of women's rights.

Being banned from education and work, many girls are forced to marry at the age of 13-14. My older daughter is about to turn 13. It is very, very sad to know that girls of her age are being married off, that they are having children without even experiencing their own childhood, without even knowing what pregnancy is, without even knowing how to protect themselves from pregnancy. This is very heavy to think and write about ...

“Women continue to organize and resist”

What do you think about the resistance of Afghan women against the Taliban?

When the Taliban came to power, women resisted very bravely. They marched in the streets of Kabul. You remember those photos. They took photos and videos to record their resistance. They were beaten, their cell phones were taken away from them. Women took serious risks; they were jailed. Many paid a high price just for defending their most basic human rights.

We don't see this kind of street protests now. This is one of the signs that the Taliban government is moving forward with oppression and tyranny. But that doesn't mean that there is a lack of resistance. Women are organizing and resisting through the internet and in other ways.

Surviving in these conditions - staying in the country or leaving the country but continuing to live; making women’s voices heard and experiences visible by pushing the doors that are not easily opened to women in international fora and fighting for the Taliban not to be recognized; these are all resistance. All of it has a price...

Women in Afghanistan are also resisting by breaking bans every single day.

For example, teachers who have been dismissed from their jobs are taking serious risks to open secret “home schools”, allowing girls to continue their education. Girls of high school or university age who have access to the internet are trying to somehow hold on to their education, and life in general, through online classes or other activities.

Where there is a ban, there will always be violators. Especially when the ban is so illegitimate, so inhumane!

Some recent studies have shown that Taliban’s bans have a very negative impact on women's mental health, leading to an increase in depression and suicides. Given what the Taliban puts them through, could it be otherwise? Is it possible to keep one’s mental health under such repression?

“Without solidarity networks, the people could not fight poverty”

What is the importance of solidarity and support networks in the face of women losing their economic freedom and being pushed into poverty? Do you think these supports are sufficient?

Social solidarity and support networks are always important. We saw the importance of this with the earthquake in February 2023 that shook 11 provinces in Turkey. Prof. Dr. Yakın Ertürk evaluated the mobilization and solidarity shown by society as “the people becoming the state” in the face of the state’s ineptitude and incapacity in managing that crisis.

A striking observation, indeed. The earthquake was both a natural and political disaster for us. It was also very traumatic.

The Taliban's return to power and its policies are also a political disaster. Of course, it was traumatic for everyone, but especially for Afghan women and girls. The Afghan people would not have been able to cope with this poverty without solidarity networks, but the situation is bad. Unfortunately, neither economic solidarity nor political solidarity is sufficient in the current situation.

The biggest economic solidarity and support networks are formed by Afghans working outside Afghanistan. In addition to the mostly male workers in Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan and Turkey, Afghan women who had to leave Afghanistan and are scattered all over the world support their relatives and friends who stayed behind. They send more than 4 percent of Afghanistan's GDP to the country. That's a lot of money! It's a big percentage! It's a big percentage that enables people to pay for food, rent, diesel, not to sell the land they have cultivated, to keep it.

Economically, there is a lot that can be done especially by countries like the US, which is politically and morally responsible for what is happening in Afghanistan.

I will give a very concrete example: It is infrastructurally possible for universities in the US (and other countries) to accept female students from Afghanistan as online students. Likewise, it is possible for companies and NGOs to prioritize applications from Afghanistan for jobs that can be done online.

Some professional associations such as the Middle East Studies Association (MESA), which is headquartered in the US but brings together academics from all over the world, has also shown serious solidarity in line with its field and mission. Although its focus is on Palestinian academics displaced by the recent war, the MESA Global Academy aims to show solidarity with displaced academics from several countries, including Afghanistan, Iran, Syria and Yemen.

I also find political solidarity and support networks important, especially the support of the women's movement for women in Afghanistan, for example in the quick reflexes they showed to organize for the non-recognition of the Taliban.

Are existing solidarity networks sufficient? No, they are not. Are they important? Yes.

What do you think the international community and the media should be doing to give a voice to Afghan women?

A lot of things are being done, but I am not sure how much they are shaping the actions of the more decision-making institutions of the “international community”. For example, feminist movements in Turkey and elsewhere are very sensitive to what is happening in Afghanistan (and Iran). But we have to admit that, what we do to give a voice to women living in Afghanistan, or those who have been forced to leave it, is limited...

Of course, in international meetings, in news media, there should be more and more visible news about the daily life of women in Afghanistan, about the oppression of women by the Taliban. All of us, where we are and what we do, can do more for this.

In March 2024, I gave a presentation on gender apartheid at a side event organized in conjunction with the 68th meeting of the UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW). CSW68 brought thousands of women's rights advocates from around the world to New York as it does every year.

In that presentation, I focused on the situation in Afghanistan and presented a gendered assessment of deepening poverty. Most of the reports that form the basis of both that presentation and this conversation we are having now are based on interviews with women in Afghanistan, their testimonies and experiences. Their voices and experiences need to resonate more widely; they need to be better understood. Not just once a year, but more often.

To be perfectly honest, there is so much war and suffering! If what Israel is doing in Gaza in front of the eyes of the world is not genocide, what is it? What do we call it?

There are no schools, no hospitals left in Gaza. There is a civil war raging in Sudan, with terrible consequences. Most of Sudan's 46 million population are children, and by October 2023, the number of children who cannot go to school due to war is 19 million!

When we look here in Turkey, there is no armed conflict (thankfully), but we do not live in “peace” either! Human rights, including women's and LGBTI+ rights, and even animal rights, are under such attacks that sometimes the urgency of what is happening in our own agenda can make us forget the gravity of the situation in Afghanistan. As I said, there are solidarity networks, and they are admirable. But we are experiencing war after war, crisis after crisis, and this is putting perhaps unprecedented strain on all social relations and solidarity efforts.

In a world where violence is so normalized, we need feminism more than ever. For everyone!

What is the latest situation in international fora? Are negotiations being held with the Taliban regime that has erased women from the public sphere? Is the Taliban recognized?

Technically, the Taliban is not recognized. For example, UN reports refer to the Taliban as the “de facto authorities of Afghanistan”, not the government of Afghanistan. To summarize very briefly: We can say that many bilateral and multilateral negotiations with the Taliban are held to engage and influence without recognizing them.

On 1 July 2024, Taliban representatives attended, for the first-time, high-level talks of Special Envoys organized by the U.N. in Doha. The macroeconomic situation, including support for the private sector and counter-narcotics were on the official agenda items. “Regional stability” and “counter terrorism” were also discussed.

The meeting was criticized, and for good reason. Women's and others' human rights were not on the agenda (because Afghanistan's “de facto authorities” did not want to discuss these. Women and other Afghan civil society representatives were not invited/involved in the talks with the Taliban representatives who were, of course, all male. (Although not on the agenda of the meeting, we learn from their own statements that UN officials and member states reminded the Taliban that women have human rights and raised this issue. They also met with Afghan women in Doha the day after the official meeting with the Taliban.

Interestingly, a woman, Rosemary DiCarlo, Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs attended this meeting on July 1, 2024, instead of UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Perhaps we can add this message to the list of creative curiosities we encounter in the “international community” whose efforts and contradictions are trying to engage the misogynist Taliban...

All of these issues are important, of course. More specifically, states that have the power to be heard more in the “international community”, including states like China and Russia, see the Taliban as bringing a kind of stability to Afghanistan. These states value “cooperation” with the Taliban to keep terrorist groups in the region under control.

Are these collaborations more important than the right of Afghan women to be represented in these high-level negotiations? Is it possible to separate the problems that women face every day, their rights to life, education and work, from the “fight against terrorism”, “security”, “economy” and “regional stability”?

Why is the Taliban's terror inflicted on women less important than the “fight against terrorism”?

What does it mean to talk about security without talking about women's human rights?

Whose security are we really talking about?

Translated from the interview originally published in Turkish with DeepL.com (free version). Some substantive edits have been made to improve clarity. All lingering mistakes can be blamed on Artificial Intelligence.