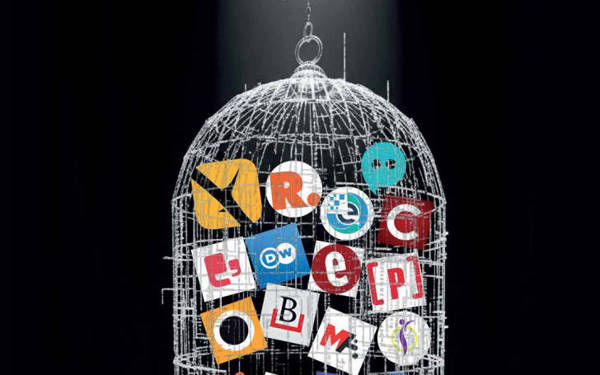

The Freedom of Expression Association (İFÖD) has released a new report titled “Digital Obedience Regime: Social Network Providers and the Illusion of Transparency in Turkey,” examining the role of social media platforms in Turkey’s internet censorship landscape.

Co-authored by Prof. Dr. Yaman Akdeniz and Researcher Ozan Güven, the report shows that global platforms such as Facebook, X, TikTok, YouTube, and LinkedIn have prioritized their commercial interests over users’ rights by complying with government censorship demands in Turkey.

According to the report, following amendments to the Internet Law No. 5651 in 2020 and 2022, social network providers that established local offices in Turkey formally complied with the legal process. These platforms largely fulfilled the obligations related to “local representation,” including setting up companies and increasing capital.

However, this compliance did not create genuine legal accountability. In practice, social media platforms have moved away from transparency and effectively turned into mechanisms of “digital obedience” for the state.

Transparency reports hinder public oversight

İFÖD scrutinized the transparency reports published by platforms including Meta (Facebook, Instagram), X (formerly Twitter), YouTube, TikTok, VKontakte, LinkedIn, Pinterest, and Ekşi Sözlük. Akdeniz and Güven described these reports as “ineffective data dumps.”

The report notes that Meta and TikTok, despite legal requirements, do not clarify which content was removed for “violation of personal rights” versus “invasion of privacy.”

Turkey blocked record number of web addresses in 2024, surpassing 300,000

Platforms also fail to clearly distinguish between content removed due to court rulings and interventions based on their own community guidelines. This approach effectively renders public oversight of censorship impossible.

According to the report, platforms use transparency reports not as tools of accountability but as “compliance documents.” Instead of enabling public scrutiny, this practice conceals the extent of state pressure.

BTK concealed data, citing ‘trade secrets’

The report also holds the Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK) responsible for transparency shortcomings, not just the companies.

Responding to İFÖD’s requests for information, BTK confirmed that platforms submitted their reports in full but refused to disclose them to the public on the grounds of “trade secrets.”

As a result, BTK turned transparency reports into “closed-circuit notifications” accessible only to the state.

Algorithmic censorship

The report indicates that many platforms, especially Google, prefer to suppress content not by removing it directly, but through algorithms that render it invisible.

Akdeniz and Güven note that arbitrary traffic restrictions on news websites, in particular, have created a form of “algorithmic shadow censorship” and narrowed the digital public sphere.

Examples from LinkedIn, TikTok, and YouTube

The report highlights LinkedIn specifically. While the professional networking platform claimed in its report submitted to Turkey that it received “zero” requests, it also revealed in its global database that it complied with 100 percent of the requests from Turkey during the same period.

TikTok complied with over 90 percent of content removal requests from Turkey, increasingly invoking its “Community Guidelines” as justification for censorship.

YouTube continued to remove content based on Article 9 of Law No. 5651, despite the Constitutional Court having annulled the provision. The platform has effectively enforced a regulation that no longer holds legal validity.

X (formerly Twitter), under Elon Musk’s leadership, significantly limited data sharing related to Turkey and failed to apply the European Union’s transparency standards in the country.

No accountability

Charts included in the report show that many of the local entities established by the platforms in Turkey function as shell companies.

It was found that the companies set up by X, Meta, YouTube, and TikTok in Turkey are managed by legal entities based abroad, and that the individuals representing them do not reside in Turkey.

According to the report, this structure is designed to evade administrative and criminal liability. İFÖD argues that this representation model undermines the principle of “effective accountability” outlined in Law No. 5651.

Warning about ‘compliant apparatus’

In the report’s conclusion, Akdeniz and Güven argue that Turkey’s legal regime and administrative pressure have merged with the commercial interests of platforms.

They state that this process has sterilized the digital public sphere, promoted a single narrative, and left users’ rights unprotected:

“When the lack of substance in the reports presented by platforms to the public is combined with the state’s secrecy around its own reports, it becomes clear that Turkey’s internet governance model has evolved into a behind-closed-doors negotiation and data exchange process between the platforms and the state, rather than a mechanism to ensure transparency.

The current legal regime and implementation practices targeting social network providers in Turkey have transformed these platforms into ‘compliant apparatuses’ of the state’s censorship and surveillance mechanisms, rather than protecting users’ freedom of expression and right to access information.

The platforms’ ineffective and non-transparent reporting techniques, their lack of resistance to protecting user data, and their continued enforcement of regulations annulled by the Constitutional Court show that the structural issues in Turkey’s internet freedom record are not only persisting but deepening.” (HA/VK)