On the occasion of International Migrants Day on Dec 18, we spoke with Duaa Muhammed, a feminist activist from Syria who was forced to flee to Turkey.

Now 20 years old, Duaa crossed the border into Turkey with only her women relatives. She shared her years-long migration experience and the story behind her decision to return to Syria. “Return is a political responsibility for me,” she said.

Duaa describes herself as “a feminist Syrian woman.” When she first arrived in Turkey, she had no knowledge of feminism and says her political awareness was shaped largely during her time there.

After being displaced multiple times within Syria, Duaa first moved to Jordan. She later returned to Syria voluntarily and lived there for about a year and a half. But with the intensifying war and increasing bombardments, she was once again forced to flee, this time to Turkey. Her family later followed. She highlights that this experience is directly tied to the current debates around “voluntary return.”

“When I came to Turkey, I had just escaped the war. In Syria, I was working under bombardment, helping people. Once I arrived here, everything stopped. There was no language, no direction.”

Duaa said she initially considered returning to Syria soon after her arrival in Turkey, but discovered she was wanted by regime forces. “If I had gone back, I would have been arrested. That’s when I realized I had no choice but to stay in Turkey.”

Discrimination

Duaa applied for scholarships to pursue university education but was unsuccessful. When she enrolled at a university in Giresun, she faced discrimination. In 2017, she said she was denied a dormitory place because she was Syrian, and private hostels also refused her accommodation.

“For the first time, I felt explicitly unwanted. I had no money left, classes had begun, and I had nowhere to stay. I had to freeze my enrollment and return.”

Following this experience, Duaa began working in civil society. She learned Turkish and obtained Turkish citizenship in 2017. Yet, she says she “never felt a sense of belonging.”

“I learned Turkish with love. But no matter what I did, people always asked, ‘Where are you from?’ That question gradually silences you. Sometimes, just to avoid hearing it, I chose not to speak at all.”

‘Being a Syrian woman means carrying double the burden’

In Turkey, Duaa says she faced both sexist and nationalist discrimination as a Syrian woman. Even in personal relationships, she was not seen as equal. She says nationality itself created a hierarchy.

“Some men saw themselves as superior just because they were Turkish. Syrian women are either pitied or objectified sexually.”

This sense of exclusion prompted Duaa to move to the UK in 2023. There, she said, she was treated “as a human being” for the first time. “No one asked where I was from,” she said, but added, “Syria is still unknown there too. You have to explain yourself from scratch.”

‘I wouldn’t return as long as Assad was in power’

Following the fall of the Assad regime in Dec 2024, Duaa recalled a sentence she had said years earlier: “I won’t return as long as Assad is in power. If he leaves, I’ll go back.”

Despite holding Turkish citizenship, Duaa decided to return to Syria with her spouse, driven by a sense of duty to the country where she had long worked in human rights and a feeling of “statelessness.”

“I’ve been working for this moment for years. If we could make a difference, that’s where we needed to be.”

A homecoming: Yaman’s journey of belonging between İstanbul and Aleppo

‘Even the grave was gone’

For Duaa, returning was not marked by celebration, but by confronting loss. She said she was only able to find her brother’s grave—he died in the war—on her third visit.

“Even the grave was gone. My neighborhood was almost completely destroyed. Half of my relatives were missing.”

She described how even within a single family, return experiences could be vastly different. While her spouse's childhood home was intact, hardly anyone remained in her old neighborhood.

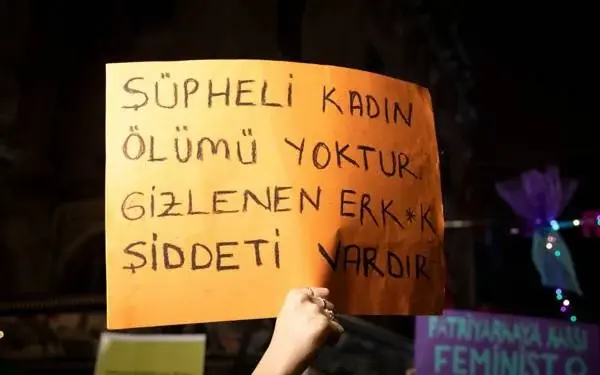

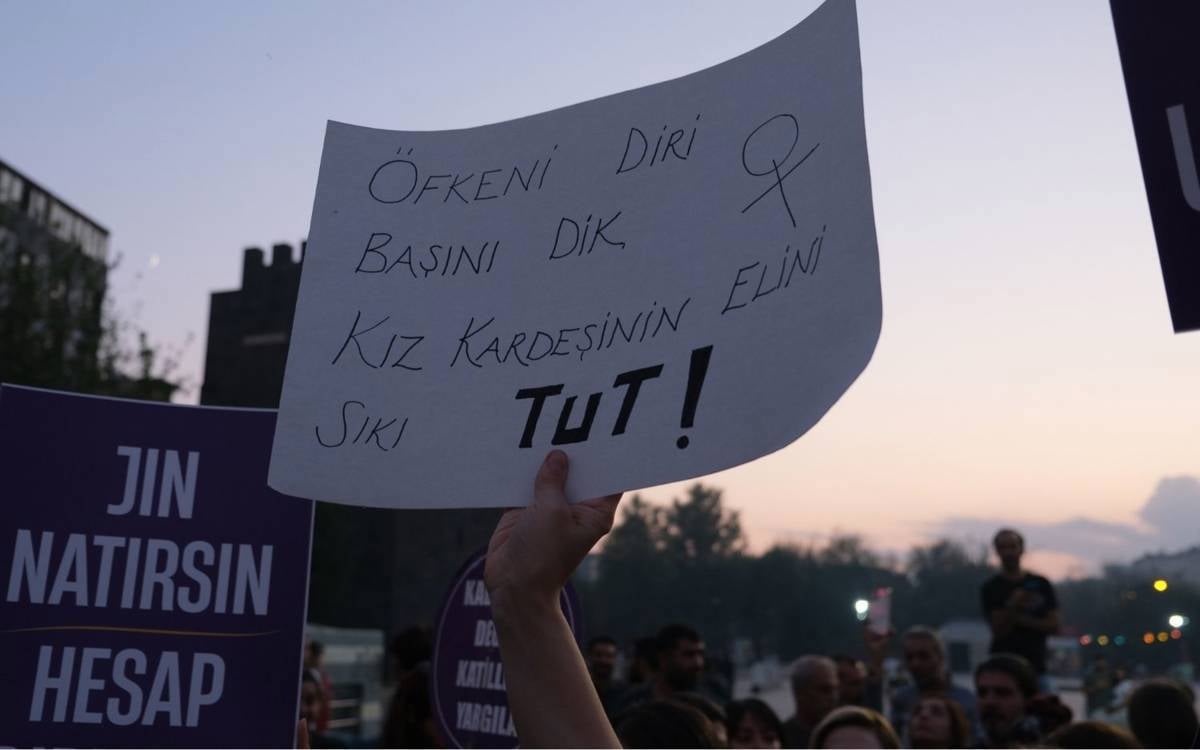

‘This is a feminist uprising’

Although she and her spouse have not yet been able to establish a permanent life in Syria and have had to relocate multiple times within a few months, Duaa emphasized that every region in the country now has its own unique reality. While airstrikes have stopped and the fear of arbitrary detention has decreased, violence has not completely ended.

“The end of Assad’s 54-year dictatorship is a huge victory. But the struggle is not over,” she said.

Duaa sees the current period in Syria as a “feminist uprising.” She says the 20 percent quota for women in parliament is insufficient and that the fight for rights continues. Syrian feminists who lived in exile during the Assad years are now trying to reorganize within the country.

“Try to understand people not just through their identity, but through their lived context. Migration is rarely a choice—it’s often about survival. Solidarity is still possible," she says. (EMK/VK)