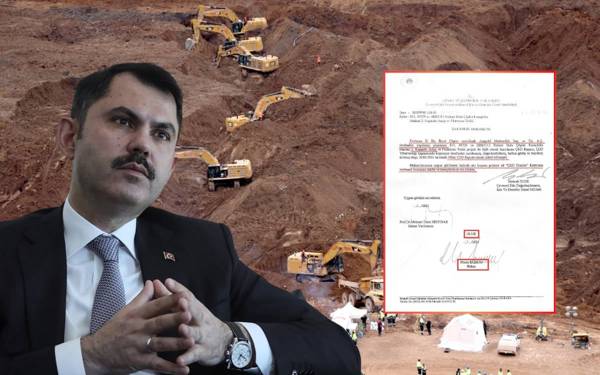

The Independent Mining Workers' Union (Bağımsız Maden-İş) prepared a report regarding the landslide that occurred on February 13 at the Çöpler Gold Mine operated by Anagold Mining, a Canadian and U.S.-based company, in the village of Çöpler in the İliç district of Erzincan.

The union outlined negligence in their report titled "Before and After February 13," released nine days after the disaster, based on observations by the delegation present in the region since the initial moments of the incident.

Trapped miners in İliç located

The most fundamental reality revealed in the Independent Mining Workers' Union's 10-point report is the overriding pursuit of "exceeding all boundaries for faster and greater production":

The goal, in the words of CEO Edward Dowling, to become the "world's cheapest, low-cost gold mine" has permeated every level of operation.

Despite the appropriate standard for the heap area allowing for a maximum slope of 10-12%, Anagold has constructed heaps on steep terrain with slopes ranging from 75-80%.

'The volume of the sliding mass in Iliç is 10 million cubic meters'

While it is known to be reasonable to ascend up to the 25th level, on February 13, there were 33 levels in the heap area.

Prior to the incident at 14:28 on February 13, unusual cracks were detected by workers on the heap, on the heap's roads (despite being constructed with stabilized heaps and compacted) and around the site, documented in photographs, and reported to authorities through both the company's risk notification system and other channels. However, necessary precautions were not taken.

'Erosion' and 'landslide' risks mentioned in the final introduction report of İliç gold mine

Workers performing the same tasks as those in Europe and the USA are employed in Turkey under unsafe, insecure, unregulated, low-paying, and pressurized conditions. Workers are coerced into working for at least 7 times less than their counterparts worldwide.

Five days before February 13, the withdrawal of the workers from the company's Voluntary Emergency Response Team (ERT), in addition to their regular duties, was deemed a "collective action," and the workers were coerced into providing a defense on this matter on February 13.

Two weeks before February 13, workers who had collectively resigned from the Turkey Mining Workers' Union decided to join the Independent Mining Workers' Union three days before the tragedy. When this decision was discovered by the company, a mass email was sent to the workers stating that if they exercised their rights under the law, including their right to join a union, engage in work slowdowns, stoppages, or similar actions to seek redress, they would face disciplinary measures, including termination.

Cihaner on the landslide in İliç gold mine: 'Unfortunately, it was clear this would happen'

One of the most significant points identified in the process leading up to the tragedy is as follows: Anagold shaped its business model from top to bottom to cut corners on worker health and safety measures and to work them longer and harder. Throughout this process, instead of hiring experienced engineers who prioritize workers' health or who express concerns about the unreasonableness of targeted production, the company employed younger engineers and managers who could work for cheaper wages and strictly adhere to company directives, even if they lacked experience or knowledge.

Additional bonuses for workers were made contingent on meeting attendance requirements, a model frequently seen in the mining industry with known adverse effects on workers. However, at Anagold, in addition to absenteeism, involvement in a workplace accident also leads to bonus deductions. If any worker, including those employed by subcontractors, experiences a workplace accident within a specified period and it is documented, bonuses for all Anagold workers are cut.

Among the workers trapped under the rubble, Abdurrahman Şahin and Hüseyin Kara worked in the piping team for subcontractor Kar-Sa Company, Şaban Yılmaz operated an excavator for subcontractor Asil Çöpler Company, Fahrettin Keklik worked in administrative tasks for the main company Anagold Mining, Ramazan Çimen and Kenan Öz were supervisors for crushing operations at the main company Anagold Mining, Adnan Keklik was a senior supervisor for ADR at the main company Anagold Mining, Uğur Yıldız worked as a truck driver for subcontractor Çiftay Company, and Mehmet Kazar worked as an operator for subcontractor Asil Keklik Company. This scenario highlights both the consequences of subcontracting and the fact that all workers in the mine and its surroundings are at risk, regardless of whether they are employed by subcontractors or the main company.

The political-administrative-economic network surrounding Anagold has also been identified throughout all processes, including Ministry inspections. (TY/PE)