Rom of Rome

50 percent of the approximately 180 thousand Roma and Sinti in Italy have Italian citizenship, 4 out of 5 live in normal houses and many work in regular jobs.40 thousand live in poor housing conditions. The investigation of Babelmed in Rome, where about 9 thousand people live in inadequate housing according to the international standards of safety, peace and dignity.

Federica Araco

Savorengo Ker ("home for all"), constructed by StalkerLab and the inhbitants of Casilino 900 camp.

Fikret Salkanovic was sixty-two years old when he died, and had nine children and fifty-four grandchildren. He had arrived in Rome from Bosnia in 1968, along with his father and brothers: the first Roma family to live in Casilino 900, one of the largest slums in Europe that stretched on a vacant unbuilt lot between Via Casilina and Viale Palmiro Togliatti, on the eastern outskirts of the city.

At the time, dozens of underclass from southern Italy lived there, especially those from Sicily, Calabria and Naples, and some Caminanti families from Noto, engaged in activities like grinding and umbrella making and retailing of agricultural products. In the early eighties, the Italians moved into the housing provided by the City. The Salkanovic, Khorakhané Cergarija, remained in their shack.

Subsequently, dozens of other Roma families from the former Yugoslavia settled in the camp. In 2010, about 750 people lived among shacks and caravans, chemical toilets and wood stoves in the 8 hectares of the camp with no paved roads, sewers or water networks. Most of these people were collecting used material to resell at flea markets or metal recovery facilities.

On the morning of January 19, 2010, by decision of the then mayor of Rome Gianni Alemanno and the Prefect Pecoraro, the bulldozers destroyed the first shack.

The eviction came after months of transfer threats, frequent interruption of water and electricity supply and worrying intimidation.

"No one objected because the City had promised the allocation of public housing and personalized employment schemes after the first four months in which residents would be accommodated in five 'equipped villages' outside the city", recalls Carlo Stasolla, president of July 21 Association [1].

In the following days, 573 people were sorted among Salone Street (200), Gordiani Street (40), the "Camping River" (173), Candoni Street (96) and Amarilli Street (64). Many decided to return to their countries of origin or to move elsewhere in Italy, by relatives and friends[2].

The report "Casilino 900. Words and images of a diaspora without rights[3]", published by 21 July Association in 2010, the costs incurred by the municipal administration for the transfer and integration of former residents of the camp in the new spaces that in the meantime had been expanded and adapted to accommodate them were revealed: a total expenditure of over 4 million euro to house "temporarily" a little over 500 people.

"Today we were able to give a different location to all the nomads who lived here," the mayor Alemanno had ruled the day when the evacuation began. "[...] This is a victory for the rule of law but it is also a victory for solidarity. This land will become a park. It will be reclaimed within one month [...] "[4].

After five years Casilino 900 is a large abandoned lot, used mostly as illegal dump, and most of its former inhabitants still live in containers where they had been transferred with the promise of adequate housing.

"The neighborhood committees hoped that a park would be built in its place. But it is more likely that the lot ends in the enormous turnover of Roman property speculation", says Lorenzo Romito, from the experimental urban art laboratory StalkerLab. In 2008, Stalker involved young Itailan and European students of architecture and some rom the camp to build a house of 70 square meters, Savorengo Ker ("home for all"), to show that it was possible to build a decent, functional and economic house for all, at the same cost of a 32 square meter container. The structure, made of wood, was set on fire by unknown assailants shortly after its inauguration. "The market value of this huge piece of land continues to increase", says the architect. "After all, Rome is a city that lives of ground rent and property speculation: everytime that there's a speculative exigency evacuation has been chosen. Sometimes they make the Rom arrive on a certain piece of land to depreciate its price or send them away to revalue it. Often they build 'equipped villages' to urbanize areas that could not be urbanized."

A "leftist" tradition

Photo taken from “Sono del campo e vengo dall'India” (I am from the camp and I come from India), Ulderico Daniele, Meti editions, 2011.

Forced evictions occurred for many years in the capital, regardless of the political ideologies of the current mayor, because the so-called "Roma issue" has always been widely exploited to rack up votes, both from the right and the left.

"In the eighties, when the first families arrived from Eastern Europe or the Balkans, the regional governments created guidelines to implement, finance and regulate what at the time were called 'temporary camps' based on the false belief that all those immigrants were Roma, and that all Roma were from a 'nomadic culture' ", explains Antonio Ardolino, from OsservAzione[5]. After working for years with the youth of the suburbs of several Italian cities, Ardolino lives in Rome since 2004 and currently deals with school dropouts, including some children living in the camps.

Lazio, Sardinia and Piedmont were among the first Italian regions to formulate regulatory responses to protect the culture and ethnicity of those groups who, although with very diverse backgrounds, walks of life and religious beliefs, were combined into one label .

"The barracks, tents or dilapidated structures of sheet metal along the crags of the rivers or on the edge of urban centers are not the typical expression of some alleged and imaginary 'Roma culture'", says Ardolino. "As the precarious and disadvantaged housing solutions for poor and marginalized suburbs around the world, from Rome to London, from Buenos Aires to New Delhi, via Los Angeles and New York."

With the disintegration of the Soviet bloc and with the outbreak of the wars in the Balkans these settlements continued to expand and the local authorities responded by building the first 'mega-camps', so-called 'equipped villages', called by some with macabre irony, 'solidarity villages', in the far suburbs.

The slums of Ponte Mammolo in Rome, where 250 South Americans, Ukrainians, Bangladeshis and Eritreans lived for about ten years until the evacuation ordered by the City Council in May 2015

The slums of Ponte Mammolo in Rome, where 250 South Americans, Ukrainians, Bangladeshis and Eritreans lived for about ten years until the evacuation ordered by the City Council in May 2015

"Between 1999 and 2000 hundreds of evictions were carried out but lodging alternatives were often rejected. That dark period of the municipal administration is remembered as the black Jubilee of the Gypsy. In the following years things have gotten even worse with the construction of the mega villages that have characterized the administrations of Veltroni and Alemanno", concludes the operator.

In 2007, after the murder of Giovanna Reggiani by a young Romanian, the Council of Ministers approved a decree with "urgent measures concerning expulsion from the country for reasons of public security" which gave full powers to the Prefect to deport every foreigner considered dangerous.

In the wake of this securitarian trend, in July 2009, the then Interior Minister Roberto Maroni signed the Nomads Plan [6] which provided, only in the capital, the construction of thirteen 'equipped villages' and the evacuation of 9 settlements tolerated until then, including Casilino 900, and 80 considered abusive. The Berlusconi government appropriated a total of 100 million euro (19.5 million just to Roma and Lazio) entrusting them to the direct management of local governments.

In 2012, the National Strategy for the Inclusion of Roma, Sinti and Caminanti was introduces at the request of Brussels, announcing the initiation of procedures for the closure of the camps and personalized shemes to housing and employment of their inhabitants. But since then, new structures have been realized in 21 Italian municipalities and evictions have become commonplace.

In Rome, the current mayor Ignazio Marino (Democratic Party), following on the "left" tradition started by his predecessors, has ordered 34 evictions in 2014 and an average of two operations per month in 2015[7].

The diaspora of denied rights

The policy of ghettoization of Roma, gradually repelled to the edge of the urban environment, contribute significantly to their social exclusion and to the phenomena of delinquency and petty crime, widespread in the camps as in all contexts characterized by strong socio-economic hardship and marginalization.

According to the latest Annual Report 2014[8] by the July 21 Association, of the approximately 180 thousand Roma and Sinti in Italy, 50 percent has citizenship and 4 out of 5 live "camouflaged" in very houses and many hold regular jobs. People living in poor housing are about 40 thousand, of which 15 thousand children at risk of statelessness because, without a residence they can not obtain the documents.

In the camps, 90 percent of people live below the poverty line, 20 percent have no health coverage and life expectancy is ten years lower than the national average. Early school leaving rates are very high: just 1 percent has access to higher education.

"The millions invested so far in the projects about education of Roma children have had little results also due to the many diseases caused by living conditions in the ghetto, affecting mainly the children. The most common are sleep disorders, cognitive delays and attention disorders", says Carlo Stasolla.

These diseases, he continues, slow down the learning of the students, who often face serious discrimination from both teammates and teachers too. And the teachers rarely have the necessary tools for the schooling of the most disadvantaged.

"Many come from uneducated families", says Emil Julien Costache, a social worker who has worked for ten years on the education of children living in poor housing conditions in Rome. "Yet, it is an increasingly widespread belief that education is an essential tool to become independent of the welfarism of the administrations. Many teachers still ask me how to work with Roma pupils, assuming that they are not at the level of the rest of the class. Marginalized from the process of learning, relegated to the back row alone to paint for whole mornings, many children reach the fourth grade without knowing how to read or write. Others, however, abandon the path after attending professional courses, when they discover that they can not take the final exam because they don't have the documents. Those, who finally, with or without a certificate, look for a job are often excluded because they are Roma."

"Drug trafficking makes less money"

"We have closed this year with forty million turnover but all the money, the profits, we've made on Gypsies, on emergency housing and on immigrants, all other sectors end up at zero. Drug trafficking makes less"[9]. This is what the president of the Consortium of Eriches Cooperative, Salvatore Buzzi, says during the phone call intercepted for "Middle World" investigation by the Public Prosecutor of Rome. Investigations have revealed a complex corrupt system with a mafioso mold that for years has managed in collusion with local governments the procurement and allocation of public funds with huge interests in the implementation and management of the camps.

Currently 4400 Roma and Sinti live in the equipped villages in the city, 1200 in "collection centers", 700 in tolerated camps and about 2500 in informal settlements.

The report Campi nomadi S.P.A. Segregare, concentrare e allontanare i rom. I costi a Roma nel 2013 [10] (Gypsy camps S.P.A. Isolating, concentrating and removing the Roma. Costs in Rome in 2013) showed that more than 90 percent of the 24 million euro invested that year in the camps of capital was spent to cover operating expenses.

The ghetto economy also allocates large sums of money for the purchase of sophisticated surveillance systems, fencing and monitoring, containers and chemical baths and to carry out numerous evictions [11].

"An emblematic example was that of Val D'Ala, in July 2014, which cost 168,400 euros to the municipality", tells Stasolla. "After our protests, the 39 evicted Roma (mostly children) were accommodated at the Fiera di Roma and after its closure, repatriated to Romania. A few months later, as EU citizens, they returned, settling exactly where they were at the beginning. Passing the Roma around is like passing the garbage around in a grueling game of the goose that never come to anything: the more they are moved the more the institutions managing the operations of evacuation and reception earn". In the case of Val d'Ala, it was the Consotium of Solidarity House to cash in on all that public money. The Consortium at the time ran the Fiera di Roma, and a few weeks ago its president, Tiziano Zuccolo, was arrested for criminal association and aggravated corruption.

"The great risk that we fear is that, to subtract contracts to these subjects, now under investigation or in jail, people may end up in the street", says Stasolla, proposing to close the camps and providing decent housing to their residents, "proceeding in parallel with the dismantling of the criminal network and the mafia which for years enriched 'at the expense of the Roma'."

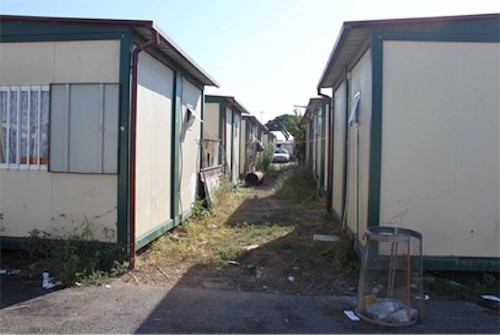

The image is taken from the report "Campi Nomadi S.p.a (Nomad Camps Spa), by the 21 July Association on the biggest "solidarity villages" in Rome. The Cesarina camp was closed in December 2013.

A landmark ruling

After numerous reports and complaints by the July 21 Association and the Association for Legal Studies on Immigration (ASGI), on 9 June, the Civil Court of Rome issued a landmark ruling that defined the so-called "equipped villages " illegal because of their ghettoising nature on ethnic grounds. The case relates to La Barbuta camp which was immediately closed. "Created in 2012 by the Alemanno junta", says Stasolla, "the camp is in an area that is not possible to urbanize for three reasons: it is under the cone of flight from Ciampino airport, it is above an aquifer and also above a necropolis. In the state of 'emergency' the project manager Scozzafava, imprisoned former councilor for social policies of the Alemanno junta, has waterproofed the ground, brought water, light and sewers and I wouldn't be surprised if the area is was parceled in the future. I should add, finally, that the land was donated to the municipality, in circumstances yet to be clarified, by the treasurer of the Magliana Gang (Banda della Magliana)".

"We hope that the administration proposes a road map for the closure of all the camps within two years and the gradual integration of their residents into the social fabric of the city" said lawyer Salvatore Fachile from ASGI after the ruling. "If this is not done, we are ready to present similar complaints about all the other equipped villages in Rome and seek compensation for the residents of La Barbuta who have lived in discrimination."

Federica Araco

Translated from Italian by Övgü Pınar

2 - "The first to suffer from this eradication were children of school age, forced to change suddenly during the academic year their classmates and teachers", adds Stasolla, who with the 21 July Association conducted a brief search on 247 young people who had been transferred. The data collected showed that in the school year 2009-2010 at least 37 Roma children enrolled in compulsory school had had to leave their studies because of the eviction and that more than 70 children interrupted the school for at least two months.

3 - Casilino 900. Parole e immagini di una diaspora senza diritti (Casilino 900. Words and images of a diaspora without rights), by the July 21 Association, written by Andrea Anzaldi and Carlo Stasolla, editing Danilo Giannese, Photographs Alessandra Quadri, Rome, 2010.

4 - From the interview of 16 February 2010 published on the blog "Alemanno 2.0", Chiusura Casilino 900 (Closing Casilino 900).

5 - http://www.osservazione.org

6 - An article in the Corriere della Sera reports the data of the operation in Rome and Lazio: http://roma.corriere.it/roma/notizie/cronaca/09_luglio_31/piano_nomadi_roma-1601621809519.shtml?refresh_ce-cp.

7 - Among the most recent episodes is the demolition of the settlement in Ponte Mammolo, where Eritreans, Ukrainians, Romanians, Indians and South Americans lived in conditions of extreme hardship for ten years. Although there was no Roma or Sinti among them, most of the Italian press reported the news talking about a "nomadic" camp, confirming and strengthening the popular, mediatic and political imagination, fruits of decades of propaganda that considers these groups culturally incapable to live in normal housing conditions.

8 - http://www.21luglio.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Rapporto-annuale-Associazione-21-luglio.pdf .

9 - From an article published in "Il Fatto Quotidiano" on December 2, 2014.

10 - http://www.21luglio.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Campi-Nomadi-s.p.a_Versione-web.pdf

11 - Another interesting report on the costs of systematic segregation of Roma in Italy is Segregare costa. La spesa per i ‘campi nomadi’ a Napoli, Roma e Milano (Segregating costs. Spending on the 'nomadic camps' in Naples, Rome and Milan), published in 2012 by Berenice, Compare, Lunaria and OsservAzione: http://www.lunaria.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/segregare.costa_.pdf .

With the support of:

![]()

Click here for the details of Babelmed Project "R.O.M. Rights of Minorities