Once an image meant presence, if not the hours or even years of a painting, then a snap to signify that that person who saw it was there, felt it, and later let it process in the chemistry of its development, so as to convert silver into history.

Whereas artists and writers have demanded time and space apart from the world to knead thought and impulse into movements of cultural drama as they ensued across the seas of human life, photographers captured that slight window of opportunity, nearly two centuries between the mid-19th century and the advent of the digital imagination, when their renderings were invaluable figments of actual, lived experience.

This is the art of Robert Capa, a comprehensive dash of whose life’s work is brilliantly exhibited by the Ara Güler Museum, an establishment that might make its namesake proud for its vivid, immersive pictorial invention, offering the late photojournalist, who died tragically early in 1954 on assignment in Vietnam, a laudable posthumous homage.

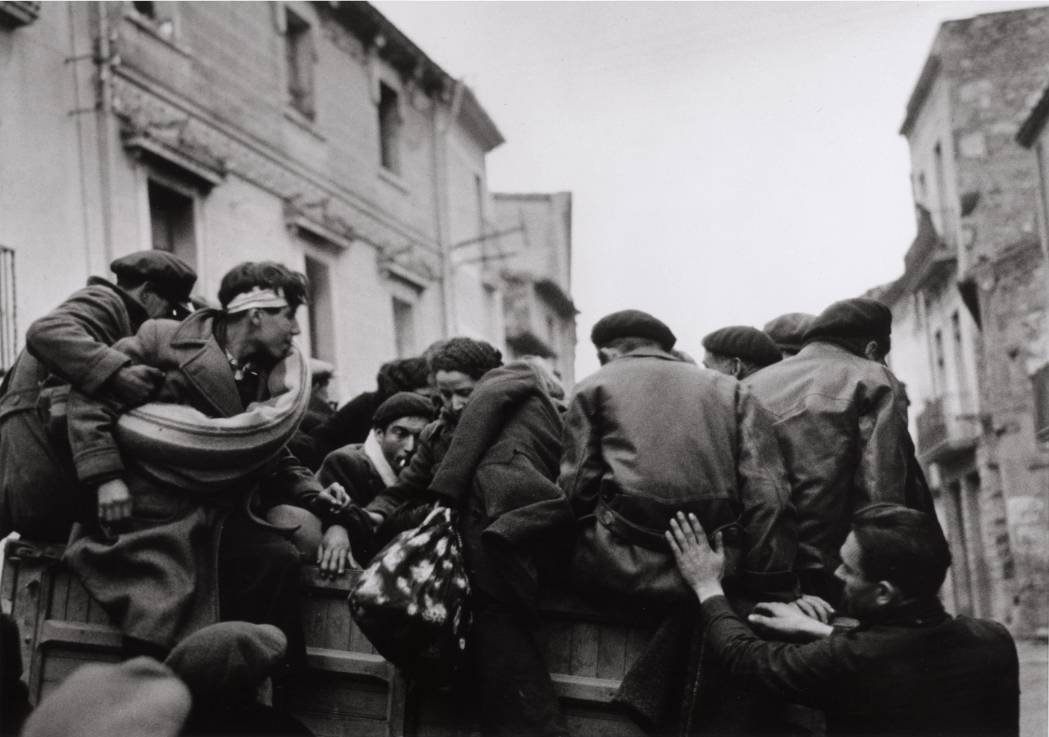

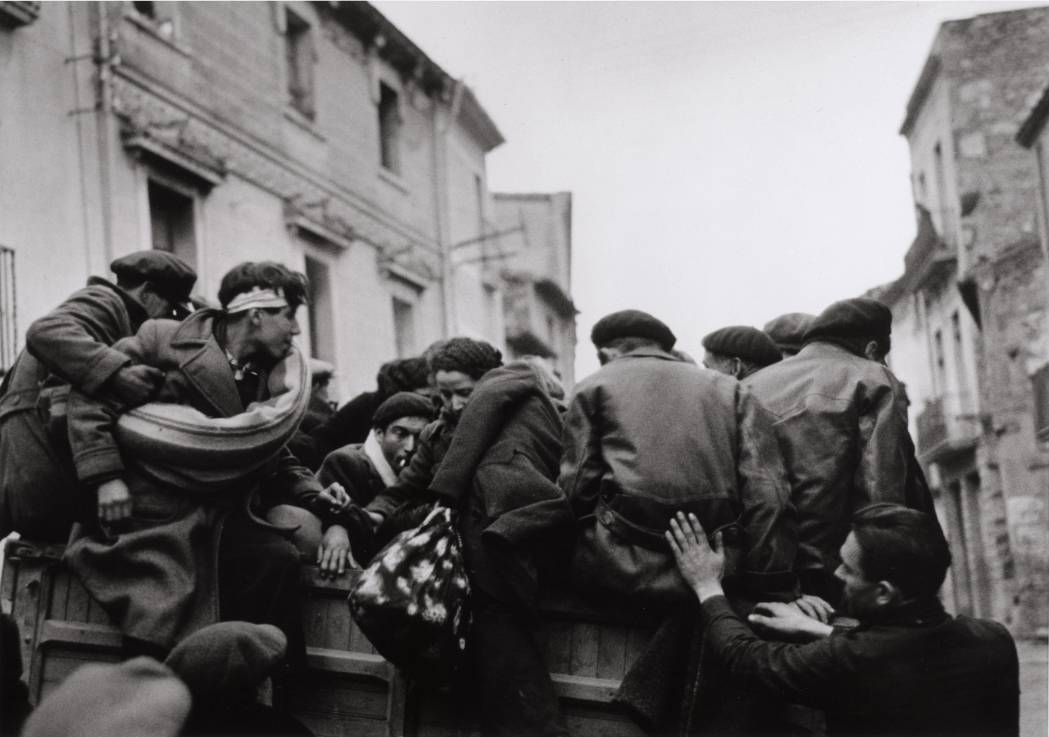

For the first time, Capa’s photographs of his Turkey expedition are glamorously upheld beside a wide-ranging tour of his decades from the Europe to Asia, the two continents where he did his best-known work, most famously the Fallen Soldier (1936) from the Spanish Civil War, of a man who has been shot in the field of battle, and The Magnificent Eleven (1944), referring to the number of his surviving stills taken at Omaha Beach during the U.S. landing at Normandy. That he also held onto his own life is as miraculous and affecting as the blurry revelations of the common soldier at war.

Capa was born Endre Friedman in 1913, in Budapest, Hungary, he later changed his name, like so many Jews of his era, to one of a more international, anglophone familiarity. The exhibition, entitled Truth is the Best Picture, after Capa’s own phrasing is a fine piece of curatorial craft at the Ara Güler Museum. Inside the well-renovated basement of a spot nestled in and among bars and cafes of the historic beer factory now hot as bomontiada, the show begins astutely with Ara Güler’s own possessions in memory of the photographer, here a book, there an article, archival prints in the private collections of Turkey’s preeminent artist of the socially realist lens.

Just as immediately, in the first of variously contiguous halls showing an extensive breadth of Capa’s work, there are his portraits with some of the 20th century’s most memorable and beloved celebrities, including Hemingway, Picasso and Ingrid Bergman, who, later, as the show details, he enjoyed something of a fleeting affair with. The man was a monolith of his age, unsuitable for marriage, dedicated with a luring passion to the animate violence of his images, which he solidified as the basis for the best war journalism ever to fly off the newsstands.

Vain he was not, however, flaunting death with a flagrance that would be the end of him, as rare are his self-portraits. There he is, in 1947, photographing his reflection, his face down, his lips clutching his ubiquitous white cigarette, standing in front of a mirror holding his camera behind John Steinbeck somewhere in Moscow, Russia. He has the coiled air of a hyperactive doer, someone whose eyes remained on the mark of the world’s biggest waves of happening. In a word his work was material, it mattered.

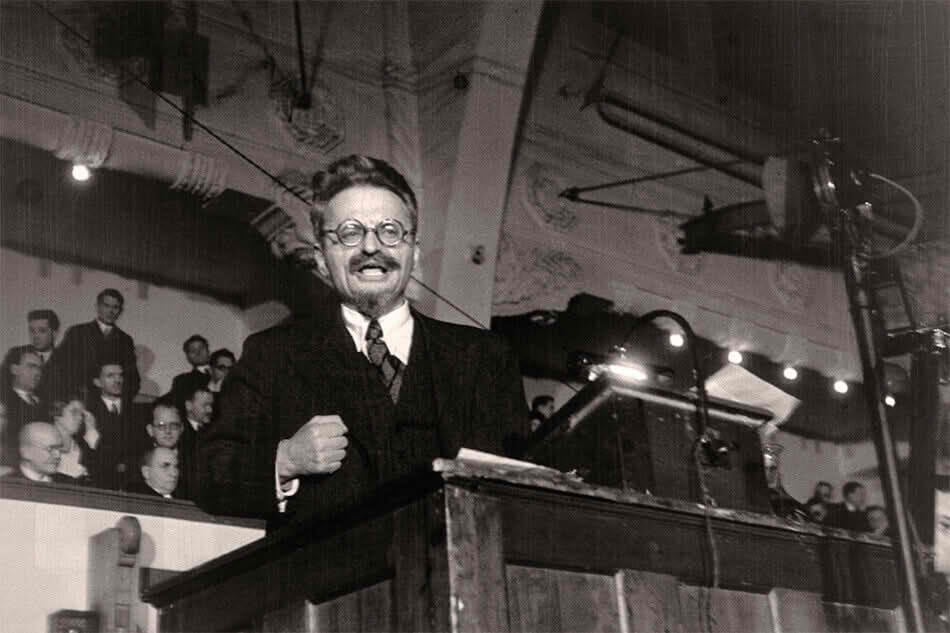

Once beyond the first impressions of his more artistic hobnobbing, there is a careful display of wall texts chronicling his biography, finely detailed, before the show opens up to exhibit a particularly grainy, sepia-toned early photograph, apparently the result of his first assignment in which he captures none other than Leon Trotsky in 1932, giving a tirade of a speech, his hand grappling with an idea, his mouth open, and the atmosphere tense with the contrasts between conformity and revolution. Already, it is possible to see in this image the workings of an eye that would remain unflinchingly devoted to the symbolism of moments, instants of portraiture and scenography and action that could, by mere sight, tell the story of a time and a place and its political fever.

Even his seemingly benign pictures, say of a group of youth watching a bicycle race in France in 1939, is full of drama, as the youngest among them clutch newspapers, the action, while out-of-frame, is all the more riveting by its suggestive draw. The curation positioned two photos of this scene, of the onlookers waiting in anticipation as the cyclists are soon to arrive, only to see them pass in the next. That racing surge of mechanical pressure, even so brilliantly in the absence of its subject, is where Capa lived. And he would die by a similar phenomenon, walking over a landmine in Vietnam embedded with French soldiers in 1954. Click. He shot a blurry capture of the ostensibly unthreatening landscape. Click. And he was gone.

Interred in a coffin wrapped in the American flag for his services to the country, the U.S. would offer him the high honor of burial in Arlington National Cemetery. His mother refused. He fought for peace, she said, not war. (MH/VK)