* Photos: Anadolu Agency (AA)

Click to read the article in Turkish

"Swedes want to stand up for democracy and human rights everywhere, but they also want security from Russia, and many feel like Ankara is now forcing us to choose between the two."

This is how  Dr. Paul Levin, the Director of Stockholm University Institute of Turkish Studies, describes the dilemma faced by Sweden on its way to NATO membership along with Finland and how the attitude of Türkiye looks from Sweden.

Dr. Paul Levin, the Director of Stockholm University Institute of Turkish Studies, describes the dilemma faced by Sweden on its way to NATO membership along with Finland and how the attitude of Türkiye looks from Sweden.

It has been over six months since the two countries applied for NATO membership following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. But Türkiye and Hungary have not yet approved their membership bids.

Commenting on Sweden's foreign policy under the new government and the country's relations with Türkiye on its path to NATO membership, Levin says that the foreign policy of Sweden had already been undergoing changes before the new right-wing coalition government came to power.

Mentioning Türkiye's possible ground offense into northern Syria, Levin notes, "I think Ankara hopes that the threat or possibility of a veto of NATO enlargement will shield Türkiye from criticism and reactions from other NATO members if it does undertake a military operation again in northern Syria."

There are two possible developments that could potentially put Sweden in a "moral dilemma": The closure of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) by the Constitutional Court and Türkiye's ground offensive into northern Syria in case of a failure of Russia's and US' diplomacy efforts.

We have spoken with academic Dr. Paul Levin regarding Sweden's foreign policy and its relations with Türkiye on its path to NATO membership.

Cold War: A turning point in foreign policy

At the last general elections in Sweden, social democrats have lost, and a right-wing coalition government has been formed in the country. How do you think this change of power does/ will affect the foreign policy of Sweden in general?

Swedish foreign policy has been undergoing changes unrelated to the change of government. The change of government has been added on top of that, pushing Sweden further to the same direction.

Russia's renewed invasion of Ukraine on February 24 has triggered a re-evaluation of Swedish security and foreign policy.

For a very long period of time, Sweden was a neutral or non-aligned country towards neutrality in case of war. That became almost a matter of identity in which Sweden positioned itself during the Cold War.

At the end of the Cold War, the policy of non-alliance aiming toward neutrality became less relevant. Once Sweden joined the European Union (EU) in 1995, we had to abandon the policy of neutrality because of it but we remained non-aligned.

In the meantime, there had already been extensive collaboration with NATO and the US during the Cold War "behind closed doors", if you will. Interestingly enough, the Swedish policy of neutrality was always depending on military support from NATO and the US in case of war.

With Russia's increasingly belligerent behavior starting with Georgia and then Ukraine in 2014, supporting extreme right movements across Europe, intervening in elections and then in December of last year, the letters to a number of states, including Sweden and Finland, demanding that NATO not enlarge further, all these developments propelled a shift in Swedish foreign policy.

So, when we joined the EU, we abandoned the policy of neutrality and we have now abandoned our policy of non-alignment when we applied for NATO membership.

'Emphasis is now on Swedish security, interests'

Even during the time of the former government, there was also a bipartisan consensus on increasing spending on armament and defense.

The new coalition government has initiated a policy whereby the foreign aid budget will be shrunk further, the feminist foreign policy has been abandoned and there is a greater emphasis on collaboration with countries in our near abroad and in Europe.

The emphasis is now on Swedish security, Swedish interests and collaborating with our near abroad. That is the general shift.

'Many find meeting with Erdoğan unbecoming'

The joint press conference of Erdoğan and Kristersson on Nov. 8. (Credit: AA)

Türkiye, Finland, and Sweden signed a memorandum in late June so that Türkiye would approve their NATO membership bids. Since then, Sweden has taken a series of steps, including lifting the arms embargo on Türkiye. How do the public and politicians respond to this memorandum and the steps taken by their successive governments? Is there anything that you personally find problematic or controversial in this context?

There is a lot of criticism from many corners in society about what are seen as concessions. There were many voices raised about the recent visit of Sweden's Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson to Turkey.

Many saw it as "unbecoming" or were uncomfortable, seeing a Swedish Prime Minister meeting with a person seen by many people in Sweden as an authoritarian leader and him not mentioning the matters of democracy, human rights or a peaceful resolution to the Kurdish conflict. Instead, he just emphasized the "legitimate security interests" of Turkey, saying that "Sweden understands its concerns and will address them." This is a big shift in Swedish rhetoric.

Many activists and representatives of the Kurdish diaspora in Sweden have raised concerns. There has also been criticism from the Social Democrats, interestingly enough. Because they were actually in charge of the government that initiated these policies. But they now feel that the current government has gone further than they needed to.

'Security on the one hand, rights on the other'

I think that it is important to note that Swedish policymakers face an underlying conflict of interests or a conflict of objectives.

On the one hand, seeing that Ukraine as a partner of NATO but not a full member was left to fend for itself in the face of Russia's new aggression, there is a rather broad consensus in Sweden that we need to seek security in a defense alliance. In order to do this, we need to convince countries like Turkey and Hungary to accept our membership application.

You could also say that Turkey has some legitimate demands. It is not unreasonable for Turkey to ask Sweden to lift its arms embargo on Turkey while seeking membership in a defense alliance with Turkey, for example. And all countries are entitled to defend themselves against terrorist attacks.

On the other hand, there are serious concerns about the way Turkey pursues its war on terror. There are concerns about the treatment of the Kurdish minority in Turkey and other human rights abuses, as evidenced by a large number of verdicts against the country before the ECtHR.

I think those sets of concerns as well as concerns about not violating the rule of law in Sweden – and about the safety of the Kurdish minority in Sweden - potentially conflict with Swedish security concerns in this case. Swedes want to stand up for democracy and human rights everywhere, but they also want security from Russia, and many feel like Ankara is now forcing us to choose between the two.

I think this is a real conflict of values and objectives. There are really no easy or good answers or solutions to it. One answer would be withdrawing Sweden's application for NATO membership and saying that Sweden will not heed any of Turkey's demands, but that would put Sweden and Swedish citizens (including Kurdish and Turkish-origin Swedes for that matter) at a greater risk from Russia.

'Threat of veto' and possible ground offensive

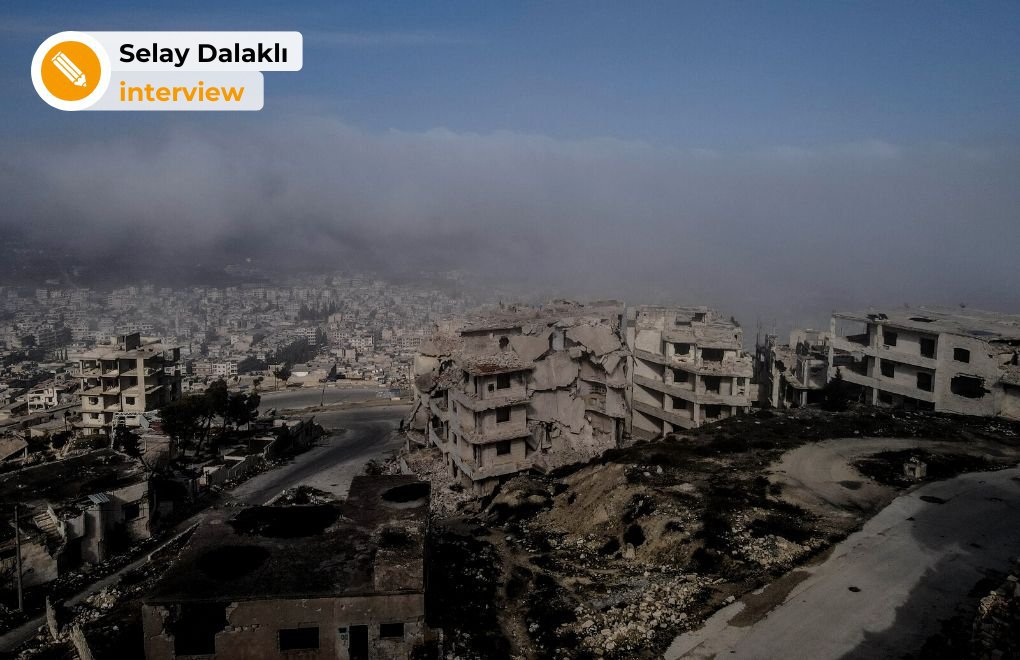

Syrian arms allegedly sends military reinforcement to the Kobanî border. (Credit: Rûdaw)

When we look at the Swedish responses to Ankara's demands, there are elements of them that are cosmetic, if you will; they have to do with public diplomacy. And then there are more concrete policy responses.

I think it is important to separate these two from one another because not doing so has led to some exaggerations such as that Sweden is practically abandoning the rule of law. That is not the case.

If you look at the actual concessions that Sweden has made, the biggest concession or the most significant response to Turkey's concerns has in my view been lifting the de facto arms embargo on Turkey. Even this is somewhat limited because Sweden is not now exporting weapons to Turkey, but exporting arms materiel that had to do with electronics, software and software support.

Still, this is a real concession as we are now at a moment when Turkey is considering a renewed military operation in northern Syria. In this context, I would say that this is not unproblematic, also considering that the de facto embargo was placed following Turkey's incursion into Afrin in 2019.

Turkey is now holding the threat of the veto of NATO enlargement as a sort of Damocles' sword over both Sweden and Finland, as well as the rest of NATO. I think Ankara hopes that the threat or possibility of a veto of NATO enlargement will shield Turkey from criticism and reactions from other NATO members if it does undertake a military operation again in northern Syria.

'Some concessions look bigger than they are'

But I think the other supposed concessions look bigger than they are. For instance, when it comes to maintaining a distance to the PYD/ YPG... This is primarily a public diplomacy loss for the PYD as Sweden has de facto never had direct ties or support to the PYD.

So, from the Swedish perspective, the reason why it was acceptable to phrase it as such in the memorandum was that it was describing something that Sweden had never done. The exception may be actions within the framework of the anti-ISIS coalition but these were limited.

For instance, there have been no arms exports to the YPG. Sweden does provide humanitarian aid to the people of the region but no financial support to the PYD.

There are also policy changes in terms of sharpening the Swedish anti-terror laws and even amending the Swedish constitution that have been described as concessions when they were not. They were based on legislative proposals that had been prepared several years earlier.

So, these are "concessions" that look worse than they actually are.

'The Supreme Court has the last work in extraditions'

The Swedish Supreme Court. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Given the steps taken so far, what specifically do you think Sweden will or can do further so that Türkiye finally approves its NATO membership bid? Is the extradition of political exiles likely to follow? And how reconcilable would that be with the rule of law?

I think it is important to separate extraditions from deportations here, because these two are dealt with in two separate manners. You can say that the rule of law and the autonomy of courts and agencies in Sweden are being tested in this process but so far they have held up.

Two consecutive Swedish governments as well as the memorandum in June have stated that Sweden will consider, in an expedited fashion, Turkey's demands when it comes to extraditions and deportations but that nothing will be done in a manner that is not in line with the Swedish rule of law or with the European Convention on Extraditions.

When it comes to extraditions which Turkey demands and the person in question does not accept, the case file is sent to the Supreme Court, which makes a determination. In a few cases, people have been extradited. In most of the other cases, the requests have been denied.

The requests have been denied for a number of different reasons: Either the person is not in Sweden or the person is not a citizen of Sweden, in which case he or she cannot be extradited, or the evidence provided is not sufficient and the court proceedings in Turkey are inadequate.

Or, as has happened in cases of people accused of terrorism by Turkish authorities, the Supreme Court does not believe that the persons in question will get a fair trial in Turkey, that they will be subjected to torture or persecution in their home country, or the acts they are being accused of do not amount to crimes according to Swedish law. When the Supreme Court has made a negative determination, the Swedish Government cannot then decide to extradite the person in question even if it would like to.

So, if you look at the precedents, you can easily predict that there will be no extraditions unless the Supreme Court radically changes its practice. Considering their recent statements, I believe that the current NATO negotiations change nothing. So, I think extraditions are a dead end unless the rule of law improves in Turkey.

What makes deportations different?When it comes to deportations, it is another matter, because here it is the migration agency that decides, and we have seen cases of deportations of terrorist suspects in recent years. The most recent one was in 2020, when a person suspected of ties to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) was deported to Turkey. I do not exclude deportations to Turkey even of terrorist suspects for a number of reasons. One is that we saw it in the past. Another is that there are over 30 cases reported in the press of people who have either sought political asylum in Sweden or have or have applied for permanent or temporary residence in Sweden but not citizenship, where the Swedish Security Service has made a determination that they have ties to the PKK. Therefore, their application for residence or asylum has been denied by the migration agency. So, as per the law, they should be extradited to Turkey. Those determinations by the Swedish Security Service go back to some 2 years in some cases. In other words, they are not concessions to Turkey. There is another fact that goes with your first question: The current government has been pursuing a much stricter migration policy and I frankly do not know if that will affect the migration agency's determinations in these cases. But I would not exclude it. |

'Stricter migration policies will have consequences'

As a Turkey expert, I would personally say that it is problematic to deport even terrorist suspects to Turkey, because the rule of law in Turkey is deeply flawed today.

There are reported cases of torture and mistreatment of prisoners. So, I would not recommend that the migration agency deport people to Turkey. But I can also see that happening because there have been other deportations in the recent past to other countries that I think are problematic.

The Swedish public has voted for a much stricter immigration policy, and that has consequences for asylum seekers and immigrants. Sometimes tragic consequences.

One can certainly criticize Sweden's migration policy but I do not necessarily see it as a violation of the rule of law in Sweden or a concession to Turkey.

So I think the question of deportations is an open case. The Swedish authorities have been saying that no Kurds in Sweden who are Swedish citizens and do not have ties to the PKK should be worried about extraditions or deportations. But asylum seekers who have had their applications denied due to suspected ties with the PKK are another matter.

I also think that we will see developments in line with the tougher Swedish anti-terror laws that are now entering into effect.

PKK is on the EU's (and Sweden's) terrorist watch list. There was a judgement yesterday handed down by the European Court of Justice that may or may not change this, but in a nutshell, I would say that as long as the PKK is on the terrorist watch list, it seems that in the future we will see legal action to prohibit fundraising, organizing and recruitment in Sweden.

'HDP's closure would lead to a moral dilemma'

844-page indictment of the HDP closure case notified to the party. (Credit: HDP)

Lastly, what would put Sweden in a dilemma or between a rock and a hard place in this context?

I have said several times in Swedish media that there are two things that may happen that would put the Swedish government in a moral dilemma, if you will, where those two objectives that I mentioned earlier, namely protecting the Swedish national security and standing up for broader concerns for democracy and human rights, may come into a very sharp conflict.

One of them would be if the Constitutional Court of Turkey moves to close and outlaw the HDP ahead of the elections next year.

This should prompt an international reaction, including from countries like Sweden, which has a large Kurdish diaspora and has traditionally always stood up for Kurdish rights. The HDP is not a terrorist organization and any attempts to criminalize it would be problematic when it comes to freedom of assembly and the fundamental democratic right to organize a political opposition.

'Invasion would also be a reason for dilemma'

The other thing would be an invasion of northern Syria. We have recently seen extensive airstrikes, including those against civilian infrastructure. But we have not seen forceful responses from other countries so far.

The Swedish Foreign Minister Billström has only said that Turkey has a right to defend itself, but I think many outside observers and experts on international law would question the description of these strikes against civilian targets as matters of self-defense, especially since so much surrounding the bombing on Istiklal Caddesi remains murky.

And Turkey is now threatening a ground offensive with potential targets including Kobanî, which is highly symbolic for many Kurds, partly because it was the place where the YPG militias started to curb the ISIS advance.

So, if a ground assault were to take place, I think it would be very difficult for the Swedish government to try to maneuver between not antagonizing the Turkish government in order to ensure its approval of Sweden's NATO membership bid and standing up for important principles regarding non-intervention and non-aggression and the right of minorities as well.

So, that is something that I will keep my eyes on, and that may actualize within a matter of days unless US and Russian diplomacy manages to stave off an invasion. (SD/VK)

.jpg)