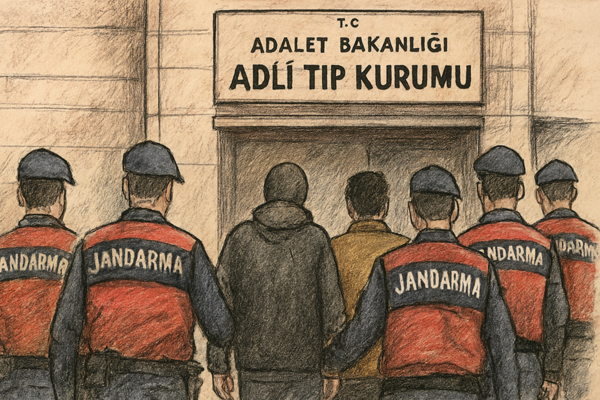

The Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office’s Bureau for the Investigation of Smuggling, Narcotics, and Economic Crimes launched an investigation into several public figures on charges of “using narcotic or stimulant substances,” leading to a raid by gendarmerie teams.

During the operation, Dilan Polat, Engin Polat, İrem Derici, Kubilay Aka, Kaan Yıldırım, Hadise Açıkgöz, Berrak Tüzünataç, Duygu Özaslan Mutaf, Demet Evgar Babataş, Zeynep Meriç Aral Keskin, Özge Özpirinçci, and Mert Yazıcıoğlu were taken to the Provincial Gendarmerie Command to provide statements and blood samples.

Although the celebrities were escorted from their residences by gendarmerie officers for questioning, Anadolu Agency reported that no formal detention orders were issued against them.

Statement from the lawyers

Meanwhile, according to entertainment reporter Birsen Altuntaş, actress Zeynep Meriç Aral, who was waiting to give her statement and began lactating, requested a breast pump from the gendarmerie. The gendarmerie fulfilled her request.

Attorney Ayşegül Mermer, representing singer İrem Derici—one of the names taken in for questioning—made the following statement:

“We are going to the gendarmerie unit for my client İrem Derici to provide her statement as part of an ongoing process. At this time, we have not been given any official information regarding the content or subject of the case. The public will be informed as the situation becomes clearer.”

“A compulsory appearance order can only be issued by a judge or a public prosecutor”

Attorney Deniz Yazgan emphasized that taking individuals from their homes without their consent, without a “compulsory appearance” order, violates both Turkish law and European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) case law:

“According to Article 145 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CMK), if a person is to be questioned, they must first be invited to appear. In the sense of CMK 145, this invitation is a ‘call made without a compulsory appearance order.’ The invitation by law enforcement, a prosecutor, or a judge presumes that the person will come voluntarily. This invitation may include a warning that ‘if you do not come, you will be compelled,’ but no force may be used against someone who decides to come voluntarily.

“If the person fails to appear without a valid reason, a compulsory appearance order can be issued by a prosecutor or a judge. However, it should be noted that a compulsory appearance order can only be issued by a judge or public prosecutor. Law enforcement cannot issue such an order on their own initiative. If there is no compulsory appearance order and the person is taken from their home without consent, and law enforcement uses force without a prosecutor’s decision, this constitutes a violation of the right to liberty and security under Article 19 of the Constitution, Articles 145–146 of the CMK, and Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Such practices have been classified in ECHR case law as ‘arbitrary deprivation of liberty.’”

Nemo Tenetur Principle

According to Yazgan, the collection of blood samples from those detained violates the principle that “no one can be forced to produce evidence that incriminates themselves. This is the Nemo Tenetur principle.

Yazgan explained that taking such samples is interpreted as obtaining physical evidence independently of the person’s will, forcing suspects to provide samples. He elaborated on this violation as follows:

“Article 75 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CMK), which regulates the examination of the body of a suspect or defendant and the collection of samples, conflicts with the Nemo Tenetur principle—rooted in Roman law and reflected in Article 38, paragraph 5 of the Constitution—which states that no one can be compelled to create evidence against themselves. This regulation puts both legal professionals and medical practitioners in a dilemma. Deriving evidence against a person from a sample taken from their own body has long challenged criminal procedure doctrine and jurisprudence.

“In Turkish law, such sample collection is interpreted as obtaining physical evidence independent of the person’s will, meaning that individuals treated as suspects are compelled to provide samples.

“Furthermore, Article 18, paragraph 1 of the Regulation on Body Examination, Genetic Analysis, and Determination of Physical Identity in Criminal Procedure stipulates that ‘Even if all conditions required by the legislation are met and the suspect, defendant, or other individuals have been informed, if they do not consent to an examination or sample collection, the relevant public prosecutor shall take the necessary measures to ensure that the examination or sample collection is carried out.’ It is clear that this is fundamentally at odds not only with human rights theory but also with the principles governing criminal procedure.”

Jalloh v. Germany Case

“In this context, it is useful to recall the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECHR) case law, particularly Jalloh v. Germany. In that case, the applicant allegedly swallowed a small packet of drugs when apprehended. The public prosecutor instructed that the applicant be administered an emetic to recover the packets from the stomach. Although the applicant refused the medication, the police forcibly administered it, and the drugs were recovered as a result.

“The ECHR recognized that the procedure was in accordance with German law but found that it violated Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and consequently the right to a fair trial was also violated. The Court emphasized that forcibly administering an emetic constitutes an interference with a person’s physical and mental integrity, that less invasive means could have been used to obtain the evidence, and that the intervention caused fear, humiliation, and degradation, qualifying it as inhuman and degrading treatment.”

(TY/MH)