Click to read the article in Turkish

According to the most recent statutory decree declared by the Turkish government on December 24, 2017, as many as 60 thousand prisoners, who are tried within the scope of Anti-Terror Law, will be forced to wear prison uniforms in the courtrooms.

The authorities present the prison uniforms in the US and Guantanamo as justifications to the recent policy.

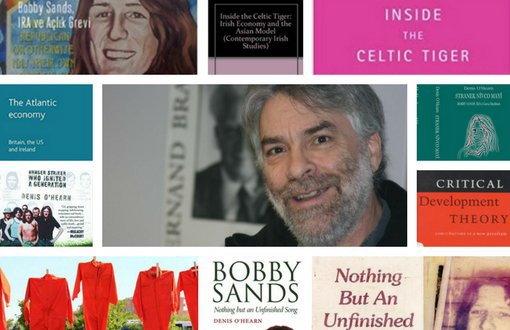

Denis O’Hearn, Head of Department of Sociology at Texas A&M University, evaluated the prison uniform enforcement. O’Hearn is a scholar of Marxist and anarchist political economy, and has done research on the prison regimes and resistances.

Proposed prison clothing policy is in direct violation of the UN regulations

- What are your thoughts on the enforcement of prison uniforms? What do you think are at the target of such policies?

Prison uniforms, indeed most uniforms, are part of what Erving Goffman called the “stripping” process. Prison authorities strip prisoners of their identities, in the form of their clothes, their habits, their associations and friendships. And then in return they try to give them a new institutional identity. The uniform is part of that.

If the point is to isolate the prisoner from “normal” society and to humiliate them, perhaps as a form of punishment that will eventually lead to redemption, then the more absurd the uniform, the more effective is the isolation.

If you allow prisoners to wear civilian clothes, you are admitting that they are civilians, with the rights of civilians and a place in society. To do this is antithetical to a justice system that is based on punishment and retribution, as opposed to a system of restorative justice.

- President Erdoğan gives USA and Guatanamo as examples for the enforcement of prison uniforms. Can you tell about the historical origins and the transition of the prison uniforms in the US?

Prison uniforms have been standard in many countries for a long time. In the US, especially in prison farms of the south, prisoners had distinctive striped uniforms of the kind one sees in old black and white “chain-gang” movies. These distinctive uniforms had a dual purpose. They were meant to shame prisoners by labeling them as “convicts” and thus outside of “decent” society. And in the case of chain gangs, which are essentially a form of modern-day slave labor in public places such as roadsides, the authorities argued that they prevented escapes. An escaped prisoner could be easily identified by the prison garb.

While uniforms of some kind may go back into antiquity, standard prison dress became part of the modern prison regime in last half of the nineteenth century. Before that, prisoners were often left in bare feet, which both restricted their movement and stigmatized them.

A major change in the treatment of prisoners in our time has been the rise of the United Nations as the standard-setter and watchdog for human rights. The “United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners” was passed in 1955 and then updated as the “Mandela Rules” in 2015. The Mandela Rules prohibit the use of degrading or humiliating clothing. They hold that “Every prisoner who is not allowed to wear his own clothing shall be provided with an outfit of clothing suitable for the climate and adequate to keep him in good health. Such clothing shall in no manner be degrading or humiliating.” And, further, the rules state that “whenever a prisoner is removed outside the institution for an authorized purpose, he shall be allowed to wear his own clothing or other inconspicuous clothing.”

Clearly, the proposed KHK regulations regarding prison clothing are in direct violation of the UN regulations. Moreover, I have been told that “almond,” the color of jumpsuits that some of the accused are to wear, has a second meaning in Turkey, i.e., shit-color. I cannot think of anything more degrading, even orange.

- What are the contemporary prison uniform regulations in the US? What do these regulations tell about the punishment regime in the country?

Prison regulations in the US are generally set by states, where most prisoners are held. Some are in the federal prison system. States have different regulations and they usually vary by level of restriction. In high-security prisons, for example, a prisoner might wear a green or blue top with sweatpants, while lower-security prisoners might wear khaki pants and shirts with the prison name on them. Some issue blue jeans and denim shirts. State prisons do not tend to issue jumpsuits, and certainly not orange ones. Most uniforms are more like the garb nurses wear in hospitals or like what some students wear to school. They are not generally degrading.

There have been exceptions. Joe Arpaio, the racist sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona, made certain prisoners wear pink underwear and jumpsuits as a form of humiliation. Arpaio was thrown out of office by the electorate in 2016 and was also found guilty of contempt of court and sentenced to prison. Donald Trump pardoned him in 2017 so he never served any jail time.

“Guantanamo is a center of torture and humiliation”

- How do clothing regulations within the US and the clothing enforcements in Guantanamo differ from one another? How would you interpret the policies in Guantanamo in general?

Guantanamo is a center of torture and humiliation. While some prisoners are there because of evidence that they participated in violent acts for groups such as Al-Qaeda, many were and are innocent. In some cases, they were the convenient victims of feuds in Afghanistan or Pakistan, who were turned in to the US authorities by their rivals, often for a cash bounty. The uniforms there are meant for isolation and extreme humiliation, and are also a part of sensory deprivation techniques. They are also racist since they are used against Muslims.

If Erdogan wants to use Guantanamo as an excuse for his new regulations he must also take into account that the regime was introduced by the George W. Bush government, which stated that Guantanamo prisoners there had no rights under the Third Geneva Convention[1], much less under the Mandela rules. This claim was later overturned by the US Supreme Court.

Does Erdogan want to make a similar claim: that teachers, journalists, and bureaucrats, or even petition-signers[2], have no human rights as laid out under the Geneva Convention? Let him say so and let’s see what the people of Turkey and the rest of the world have to say about such an outlaw regime.

- In your academic work, you examine policy transfers and policy convergences regarding the technologies of power including the war on “terrorists”. What kind of a role, do you think, such experience sharing among the policy makers play in the transition of the punishment regime in Turkey?

I have uncovered documentary evidence showing that the vernment in the 1990s used the experiences of other countries, especially that of British prisons in Northern Ireland under Margaret Thatcher, as justification for moving political prisoners from ward-style prisons to F-type prisons.

Gordon Lakes, who was the Head of Security for the British prison system advised the Turkish government on behalf of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture. Amazingly, Lakes advised the then-Turkish government that F-type isolation was more humane for prisoners than dormitory style prisons, even though he knew well about how solitary confinement had been used as a form of torture in Northern Ireland during the 1970s and leading up to the Irish hunger strikes of 1980-1981 in which ten Irish prisoners died.

What Lakes and other experts really intended was to use the Irish experience, and others in Europe, to advise the Turkish government about how to use isolation in a way that would disable prisoners from staging mass protests, like the Irish did. The result was the F-type regime, which uses a certain architecture and form of isolation to keep prisoners from communicating and organizing among themselves. At the same time, by having three captives in each living quarter, they can claim that they are not really practicing long-term isolation.

But, of course, the F-type system is another form of isolation and it produces unacceptable psychological and physical abuses on its inmates.

“The alternative to truth is lies”

- IRA resistance in the prisons also constitutes a significant portion of your research. Can you tell briefly about the enforcement of prison uniforms by the British government and the reaction to this policy in the case of Ireland?

Well, of course, the uniform was the major symbolic reason for the Irish prisoners’ protest. When Kieran Nugent became the first prisoner to be sentenced to the new cellular “H-Block’s” prison, he was told that he was a criminal and had to wear a criminal’s uniform. He reportedly told the prison Governor that, “if you want me to wear that uniform, you’ll have to nail it to my back.” As punishment, Nugent and hundreds of prisoners who followed him were left naked in their cells, with only a blanket to wear, and no reading or writing materials. A song that was popular at the time summarizes the feelings of the prisoners:

For I’ll wear no prison uniform

Nor meekly serve my time

That England might brand Ireland’s fight

800 years of crime

You can read about these experiences in my biography of the Irish hunger striker, Bobby Sands, which I am proud to say is now available in Turkish[3] and Kurdish[4] translations.

The point the prisoners were making was that they had been imprisoned for political reasons, not for crimes. To wear a prison uniform would be to accede to the government’s insistence that they were just ordinary criminals. It seems to me that there are more than a few Turks, Kurds, and others who could feel justified in making the same claim in response to Erdogan’s contemptible prison policies.

- In most of the cases, enforcement of prison uniforms encompasses not only political prisoners but also non-political ones. Furthermore, in some cases political prisoners are kept immune from such dress codes. How do you interpret Turkey’s recent policy that specifically target “terror-suspects” (in other words, political prisoners)? Are there similar cases historically?

The similar cases are some show trials in Europe and, of course, Guantanamo, where governments wanted to single out certain prisoners as “terrorists” and, therefore, claim that they were not legitimate political prisoners. But when you have the kind of wide-scale cases against tens of thousands of people as in Turkey today, some of whom merely signed a petition calling for peace, or tried to honestly report the news, we are moving into the territory of the absurd. This is the kind of thing we find in Orwell’s book, 1984. It is doublespeak. Or, in the language of Donald Trump, it is “alternative truth.” As every five-year-old knows, the alternative to truth is lies.

- Do you think this would be a first step to generalize the use of prison uniforms in Turkey? What does this tell about the homogenization of prison regimes transnationally?

It may be. That is hard for me to say.

I don’t think it is a homogenization of prison regimes across countries because, even in the US, where mass imprisonment began some forty years ago, there is a reversal going on. Fewer people are being imprisoned, many states have done away with long-term solitary confinement, and humiliating practices such as stigmatizing uniforms have become less common.

“They will be show trials”

- Similarly, different than most of the cases, the Turkish government does not intend (for now) to enforce uniforms inside the prisons. And enforcement of uniforms outside the prisons is a clear violation of the Mandela Rules. How would you interpret the government’s preference to enforce uniforms not inside the prisons but at the courthouses? Can you think of any other similar examples?

This means that they will be show trials. Think of the Soviet regime under Stalin. Think of other authoritarian (in)justice systems. Humiliating people who have not even been convicted is a clear violation of basic human rights and makes a fair trial impossible. These will be “kangaroo courts,” courts that simply jump over the rights of the accused and exclude the evidence that might exonerate them.

- What, do you think, this policy tells about Turkey’s punishment regime and Turkish system of governance in general?

It is an outlaw regime, outside of even the mildest conceptions of a regime guided by principles of human rights.

“Governments have no right to define us”

- You’ve been studying prison resistances in different contexts, including Turkey. Drawing from the examples worldwide, what would your suggestions be in terms of tactics and strategies to fight this policy?

I cannot tell people how to fight injustice. They must work it out for themselves, while considering the lessons of history. I will say that the people of Turkey have come a long way in the past decade. From Gezi to the peace petitions to various marches and other actions, large masses of people are learning to resist. Even small victories, like holding a park for several weeks and living a joyful self-governed life in it, builds agency and shows people that another world is possible. I think people in Turkey are more confident and aware today than they have been for a long time.

I also hear that some of the accused are planning to conduct protests against the new policy. I can give a historical example of the kind of thing that could be done. Instead of appearing in court in prison uniforms back in the 1970s, some IRA prisoners stripped in the court’s holding cells and appeared before the judges in their underwear! That set the cat among the pigeons. I believe Turkish political prisoners staged similar protests in the 1980s.

If the regime forces good people to wear grey or almond-covered uniforms, then turn them into symbols of hope and resistance. We must define ourselves. Governments have no right to define us. (HH/EA/TK)

[1] Third Geneva Convention regulates the treatment of the war prisoners.

[2] Petition signers are not jailed pending trial; so they will not be forced to wear uniforms. Yet, since they are being tried under the scope of Anti-Terror Law, this poilcy may also cover them in the future.

[3] Yarım Kalmış Bir Şarkı: Bobby Sands, IRA ve Açlık Grevi (2016, Yordam Kitap) http://www.yordamkitap.com/books.php

[4] Stranek Nîvco Mayî: Bobby Sands, IRA û Greva Birçîbûnê (2017, Amara Yayıncılık) http://www.amarayayincilik.com/urun/stranek-nivco-mayi-bobby-sandes-ira-u-greva-bircibune/