Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s 2025 film It Was Just an Accident created a major stir in the international cinema world after winning the Palme d’Or at the 78th Cannes Film Festival.

Opening with a tragic car accident, the film focuses on the pressures faced by dissidents and political prisoners in Iran.

The film, which had its Turkish premiere yesterday (Sep 17) at the Ayvalık International Film Festival, is a co-production between Iran, France, and Luxembourg. In his first film after being released from prison in 2023, Panahi criticizes the Iranian regime in a harsher tone by working without official permits. While It Was Just an Accident aligns with the social critiques of his previous works, it offers a more striking and intense narrative.

Most recently, the film was selected yesterday as France’s official submission for Best International Feature at the 98th Academy Awards.

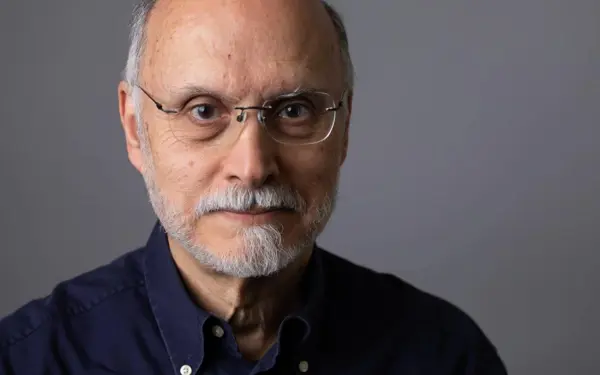

We spoke with Amir Etminan, the film’s editor, about Jafar Panahi’s cinematic vision and the challenges Iranian filmmakers face.

Amir Etminan was born on Dec 16, 1983, in the city of Salmas, Iran. Known as a film editor and assistant director, Etminan drew particular attention for editing Panahi’s 2025 film It Was Just an Accident. His career also includes works such as Khers Nist (2022) and Between Us.

'We wiped the hard drives'

We know the film was shot in Iran, under intense pressure and censorship. Can you tell us about that process?

We shot the film without official permits. We obtained a fake permit through another filmmaker and used those dates. That way, we were able to get access to certain locations for filming. It took the police 26 days to realize what was going on. They showed up one night and caught me. Panahi was already gone, and the cameras had been set up in the car. Since I was working outside, they saw me, but I quickly alerted the others when they arrived. We formatted the hard drives, so they found nothing and no arrests were made. They came with 20 people and couldn’t find a single frame. We were constantly on edge throughout the shoot—but thankfully, when this happened, we had already wrapped. We completed the film just two days later. Besides, the police and government have become wary of going after Panahi. His persecution has caused global backlash and he’s become a thorn in their side. They already have enough problems with protests and political crises.

We notice the film’s dialogue is harsher in tone compared to Panahi’s previous works. Why is that?

The repression in Iran is worsening every day. So now we speak more openly and more harshly. The pressure wasn’t this intense before, which allowed for a softer tone. Now everything is harsher. But alongside this harshness is a politically conscious young generation we’ve never seen before. Young people are bolder and refuse to accept anything. They take to the streets and protest. And it’s women leading these protests. This is a struggle, a war; it began 43 years ago and it’s still ongoing. The dialogue in the film reflects this reality—but of course, we present it in an artistic way.

For instance, the dialogue is entirely composed of phrases we received from prisoners. We had a friend who’s currently in prison. He knows nearly everything about what goes on inside because of his involvement in protests and anti-state actions. He helped us connect with young people arrested during the Mahsa Amini protests and shared their stories with us one by one. Some told us what they went through after being released. That helped us immensely. As a result, the film stopped being a purely fictional narrative.

'The technical details didn’t overshadow our story'

As someone who’s worked with him, what can you say about Panahi’s strategies for circumventing censorship by the regime?

It’s much easier to shoot films now. You can make a high-quality film with just a small smartphone. I think the story and script are the most important parts of a film—technical details are secondary. Panahi knows this very well. We started the shoot with big cameras, but as I mentioned earlier, we eventually got caught, and finished the scenes using a smartphone. And just as we expected, the technical shortcomings didn’t overshadow our story.

But for example, Panahi has faced many restrictions like house arrest and travel bans.

There’s a rule in Iran: no one can be banned from leaving the country for more than two years. They gave Panahi a 20-year travel ban. Then a lawyer appealed, stating that the ruling was illegal. Eventually, the sentence was overturned—but even then, he faced restrictions on his work. And not just Panahi; other directors have been imprisoned as well. There were protests about that too, but arrests continued. We faced similar pressure during the Mahsa Amini protests. But Panahi has always found ways to keep working despite these bans. Nothing and no one can stop him.

'We’re not afraid of repression or prison'

How do you see the place of Iranian cinema on the international stage?

I want to respond modestly—I don’t want to be misunderstood—but I believe Iranian cinema occupies a truly unique position. It offers audiences a new perspective, a different directing style, and a distinct narrative voice. One of the most important figures who made this possible is Abbas Kiarostami. The story-driven approach in Iran, the effort to liberate art even under repression, and its cultural richness make Iranian cinema exceptional. Through this method, Panahi delivers both his political messages and artistic vision with great force on the global stage. Of course, Turkey also has excellent directors like Emin Alper and Özcan Alper. And there are masters like Nuri Bilge Ceylan, who makes wonderful films. But in Iran, even under pressure, the story-centered storytelling and artistic originality are incredibly strong. Panahi represents this very well.

How do women and the new generation fit into this cinema?

The new generation is finding its voice with strength. They move freely, don’t cover their heads, and try to express themselves in the best way. Iranian women are setting an example for the world right now. I think this will be the first major women’s revolution—and it’s not over yet. Revolutions take years and require persistence.

From what I understand, you don’t seem to have any “hesitation” either?

No, we’re not afraid of repression or prison. After going through it once or twice, you get used to it; then you stop caring. Young people and women in our country are dying for their freedom—and we’re doing almost nothing by comparison. After the Cannes win, Panahi said he wasn’t afraid, even saying, “I’ll be in Tehran tomorrow. Iran is my country.” Naturally, the regime didn’t want the film to be screened abroad—but the more they tried to suppress it, the more it spread. I live in İstanbul, but I still go to Iran. Because honestly, we don’t care about the repression. That’s our country, and no one can take it from us. (TY)