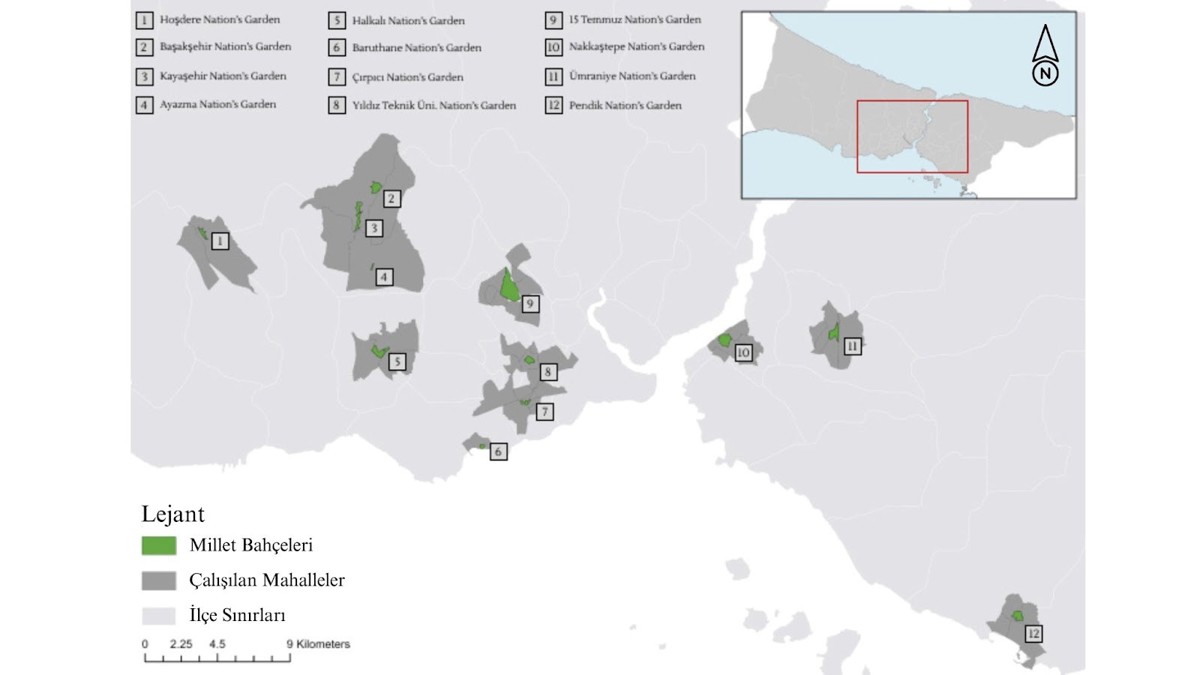

A new study examining the 12 Nation’s Gardens introduced in İstanbul between 2017 and 2021 reveals that striking social, economic, and demographic changes have occurred in the neighborhoods surrounding these parks.

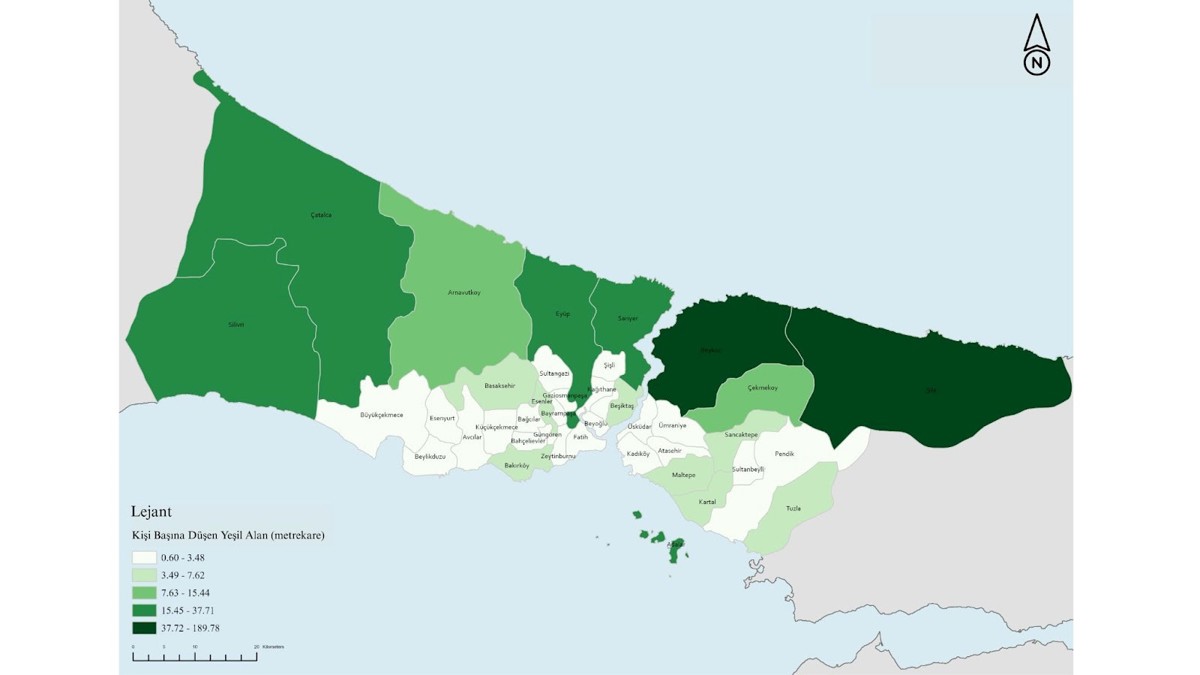

The average amount of green space per person in İstanbul is 7.2 square meters, which falls below both the minimum threshold defined by regulations and the amount recommended by the World Health Organization for a healthy life. Green spaces in the city are even more insufficient in central districts where the amount of green space per person often does not even reach 3.5 square meters. Therefore, planning new parks and gardens in the city holds the potential to improve quality of life. However, when such projects are not implemented with consideration for the entire society, they carry the risk of deepening social inequalities.

Indeed, the study shows that in 23 of the 28 neighborhoods at risk of transformation due to the newly opened Nation’s Gardens, housing prices have increased faster than the İstanbul average. For example, in the area around Ayazma Nation’s Garden, where the highest increase was observed, prices were found to have risen by 120 percent. According to the study, in many of these areas, the existing residents are gradually being replaced by wealthier and more highly educated groups.

The findings indicate that large-scale green space projects have the power to transform not only the environment but also the social fabric, and that such transformations can sometimes lead to undesirable outcomes. The study highlights that urban green transformation processes must consider not only the physical environment but also social dynamics.

Neighbors are changing with green space projects

The “Nation’s Gardens” project was introduced to the public in 2018 as a means to combat the lack of green spaces. Since its announcement, 291 “Nation’s Gardens” have been introduced across İstanbul and throughout Turkey to balance the urban green space deficit.

This project, which aims to bring the public together with nature through green corridors equipped with parks, walking paths, libraries, and social spaces, is seen by academic circles not only as an environmental arrangement but also as a tool for generating unearned profits. Indeed, new housing developments built around the project areas use their physical proximity to these gardens as a marketing tool; phrases like “with a view of the Nation’s Garden” or “neighboring the Nation’s Garden” are frequently featured in real estate advertisements.

Some gardens were introduced by renaming green spaces that were already in public use, while others were created by transforming idle areas. However, these developments have led to a noticeable increase in housing prices in certain areas, and this increase has reduced accessibility for some groups who live in or wish to live in these neighborhoods.

Criticism towards the implementation process of the project

On the other hand, the way the projects have been implemented has brought long-standing structural issues in urban planning back to the fore. In particular, the fact that Nation’s Gardens are treated as a separate category from other types of green spaces and are designed and implemented according to guidelines unique to these projects, disconnected from current planning regulations, has been criticized by urban planners for not aligning with holistic and systematic planning principles. The parks have also been criticized on various issues, ranging from the selection of their locations and the way they are named to the limited public participation in the planning processes.

Housing prices near Nation’s Gardens increase by up to 140 percent

As part of the study, 44 neighborhoods within a 500-meter radius of the 12 Nation’s Gardens completed in İstanbul between 2017 and 2021 were analyzed. Twenty-eight neighborhoods, where the elderly population and low education levels were prevalent and the average housing prices were below the city average, were defined as neighborhoods “at risk of green gentrification.”

The research results revealed that in 23 of these 28 neighborhoods, housing prices increased above the İstanbul average. The most striking increases were observed in Havaalanı neighborhood near Esenler July 15 Nation’s Garden and in Ziya Gökalp neighborhood adjacent to Ayazma Nation’s Gardens. Housing prices rose by 140 percent in Havaalanı and 120 percent in Ziya Gökalp.

When the immediate surroundings of the Nation’s Gardens were examined, significant increases in housing prices were also detected in these areas. The highest price increase, at 120 percent, was observed around Ayazma Nation’s Garden. Ayazma was followed by Başakşehir with 109 percent, Kayaşehir with 56 percent, Hoşdere with 55 percent, and Esenler 15 Temmuz with 48 percent.

'Green gentrification' draws attention to social injustices

Studies conducted in recent years show that environmentally friendly projects do not always produce equitable outcomes and that social injustices remain a significant issue in cities.

According to the concept of “green gentrification,” new parks and environmental improvements enhance quality of life. However, the socio-economic structure of neighborhoods can also change following such investments.

With higher-income and more educated groups moving into these areas, rising living costs can force existing residents to move away from their neighborhoods.

Therefore, it is not accurate to evaluate green space projects merely as environmental arrangements. These projects must also be seen as steps that intervene in the social structure of urban life.

When such transformations occur, the question of whom the investments include and whom they exclude must be central to discussions of urban justice.

10 out of 12 Nation’s Gardens changed socioeconomic structure

Looking at the overall picture, it appears that 10 out of the 12 Nation’s Gardens displayed a tendency toward “green gentrification” in at least one of their surrounding neighborhoods. The most notable examples in this regard are Ayazma, Başakşehir, Esenler 15 Temmuz, Halkalı Hoşdere, Kayaşehir, Pendik, Ümraniye Hekimbaşı, Yıldız Technical University, and Zeytinburnu Çırpıcı Nation’s Gardens.

In contrast, no changes indicating green gentrification were observed in the neighborhoods surrounding Üsküdar Nakkaştepe and Baruthane Nation’s Gardens. In these areas, classified in the study as “non-gentrifiable” neighborhoods, the already high property values and a saturated market may explain why no comprehensive spatial transformation occurred. The limited potential for development leaves these neighborhoods outside the scope of green gentrification processes.

The proportion of highly educated residents is rapidly increasing

Another parameter examined in the study was the education level in the neighborhoods. The most striking increase was observed in Kayabaşı neighborhood, which includes the Ayazma and Başakşehir Nation’s Gardens. In this neighborhood, the highly educated population increased by 70 percent. In the neighborhoods surrounding Halkalı, Hoşdere, and Pendik Nation’s Gardens, this increase also exceeded 30 percent. The only exception where an increase of this level was not observed was Oruçreis neighborhood near the 15 Temmuz Nation’s Garden.

The study also drew attention to data on the elderly population. While it was assumed that economic pressure could lead to the displacement of residents over the age of 65, a different picture was observed in İstanbul. The elderly population increased by an average of 17 percent in all neighborhoods across İstanbul; in some neighborhoods, this increase exceeded 60 percent. However, in 19 neighborhoods close to Nation’s Gardens, this increase was found to be below the city average. This situation may indicate that the elderly population was not directly displaced from these areas, but that a slow-paced demographic shift is taking place.

Green spaces in İstanbul are insufficient

İstanbul lags far behind other global metropolises in terms of green space per capita. According to regulations, this amount should be at least 10 square meters in İstanbul. The World Health Organization considers nine square meters of green space per person within a five-minute walking distance to be an indicator of health. However, in İstanbul, the amount of green space per capita is only 7.2 square meters. In 22 districts—including Beyoğlu, Kadıköy, Üsküdar, and Şişli—this amount does not even exceed 3.5 square meters.

In Europe, the average green space per capita is 72.5 square meters. Cities such as Vienna and Helsinki have approximately 60–65 square meters of green space per person. Even in cities where green space is more limited, like Athens (23) and Paris (15), these figures are at least twice the average in İstanbul. In Oslo, 68 percent of the total land area consists of green spaces, while in Vienna, this figure is 45 percent. In İstanbul, Turkey’s most populous city, years of unplanned growth and concrete urbanization have made it difficult to close this gap.

Green space policies must be equitable

Increasing the amount of green space per capita in cities is important and necessary, but the study’s findings reveal the power of green spaces to transform the social fabric and emphasize that projects must be planned with these effects in mind. In a metropolis like İstanbul, where transformation occurs rapidly both in central and peripheral areas, green space policies need to be approached from a more holistic and equitable perspective.

Findings such as rising housing prices, increased education levels, and a stable or slowly growing elderly population around Nation’s Gardens in İstanbul show that the transformation driven by green space projects does not affect all segments of society equally. When parks and gardens are not designed for everyone, they risk deepening social inequalities.

These examples of transformation observed in different parts of the city clearly demonstrate that future green space projects must consider not only the physical environment but also social balance.

In summary, urban green transformation must be designed with a right-to-the-city perspective and prioritize the needs of the local population. Otherwise, the goal of “green space for all” may end up being limited to the creation of new living spaces that cater only to higher-income groups.

Source article: Assessing a greening tool through the lens of green gentrification: Socio-spatial change around the Nation’s Gardens of Istanbul

About İklim Masası

İklim Masası (Climate Desk) is a free news service aimed at disseminating reliable information about climate change to the public. Its authors are scientists with expertise in the topics they report on.

News shared by İklim Masası may be shared or quoted partially or in full, provided that the scientist who wrote the article is cited as a reference. In cases of partial sharing, the content may not be distorted or presented in a way that removes it from its context to create misleading scientific or political interpretations.

The author of the study featured in the article is Özge Naz Pala, in collaboration with Prof. Dr. Sevil Acar from Boğaziçi University. The article was published in partnership between İklim Masası and bianet.

(ÖNP/HA/VK)