* This news is published on Atölye BİA Communication Platform atolyebia.org

** Photo: Evrensel

Click to read the article in Turkish

The number of people who seek refuge in other countries in the face of domestic disturbance, war and economic countries is gradually increasing. In the meanwhile, the refugees who have settled in Diyarbakır's poor districts such as Bağlar and Sur face discrimination and othering.

Refugee women are the ones who are otherized the most.

"Everyone is treating us as if we were beggars. I cannot even walk on the street freely. It is as if the men's eyes were always on me... They all give us an evil eye. I do not feel safe in any way at all.

"When a Syrian does something bad, they act like all Syrians were like that. When I go to the bazaar to buy something with my money and I don't like the vegetables, the seller insults me, saying, 'You came from Syria, you have ruined this place and now you don't like it here'."

This is how Rojîn Meiş, a woman who migrated from Rojava's Qamişlo to Diyarbakır's Bağlar district with her spouse and four children 8 years ago, talks about what she has been going through in Turkey.

'They call to us as "the Syrian"'

Looking back on her days and life in Syria, 36-year-old Rojîn Meiş has tears in her eyes. She tells of these days as follows:

"8 years ago, before the civil war broke out in Syria, we had a good life. We used to live on our own. My spouse had a shop, he was running it. That was how we were making our living.

"Then, all of a sudden, we could not understand what was going on. We would wake up every morning with sounds of guns and bombs.

"We decided to come here not for us, but fearing that something would happen to our children. My spouse first came here. We had relatives here, they helped him. My spouse started working in the industry, he arranged a small house. We came a year later and settled here.

"It is really hard for a person to be separated from her land and home. You would not know it if you did not live through it. But we had to come for our children. We live in a rented house now. We pay 500 lira a month for the house that you see here. Four children, all going to school... We can only get through the day with the money my spouse earns."

Meiş also talks about the discrimination and othering that she has been facing in the city where she has settled:

When they see us, they call out to us as 'the Syrian'. They do it to despise us, I know that. It really offends me when they do it. It happens so often that I go to the bazaar or market and come back in tears. When I go to the bazaar to buy something with my money and I do not like the vegetables, the seller tells me, 'You have come from Syria, ruined this place and you do not like it here.' Why? Aren't we humans, too? Don't we have such a right? I did not go to the bazaar for a long time for this reason. When my spouse asked me why I was not going to the bazaar, I shrugged it off, saying, 'We have it at home', to not make him sad. But I always suffered in silence. Only I know what I have gone through.

'I have started to get dressed like them but...'

Tired of this ill treatment, Meiş says that she has found the solution in dressing and talking like the women of Diyarbakır:

"I now wear skirts and pullovers and put on my headscarf in half like the women here so that they will not understand that I am from Syria.

"I ask the prices at the bazaar with my broken Turkish, like they do. When I used to ask questions in Kurdish, they would immediately understand that I was not from here; it must be because of the accent or something. But I am now trying to act like them. I am getting dressed like them. I have found a way in my own way; otherwise, I got mentally depressed."

Meiş notes that this bad treatment targets her children as well:

"My three children have learned Turkish at school, but as their Turkish is not like that of other children, their friends mocked them all the time. They told them, 'Why did you come from Syria? You will ruin this place, too.' My children would come back from school in tears every day. My elder son did not want to go to school anymore. I must say that both I and my children have faced so many hardships. One would endure what is inflicted upon herself, but cannot stomach what is done to her children."

Diyarbakır Bar: Refugees unaware of their rights

Lawyer Diyar Çetedir,  speaking to bianet within this context, says that refugees who live in Diyarbakır and Turkey are deprived of their several rights.

speaking to bianet within this context, says that refugees who live in Diyarbakır and Turkey are deprived of their several rights.

Lawyer Çetedir from the Diyarbakır Bar Association Human Rights Center briefly explains the situation as follows:

Refugees are both unaware of their natural human rights and afraid of applying to state institutions. There are two reasons for this: One of them is the fear of being sent back and the other one is that they cannot express themselves as they do not know the language. That being the case, they are forced to stay silent in the face of the ill treatment that they face. In other words, if someone tells them something bad on the street or harasses them, they shy away from applying to state institutions even if they are right. The main reason for this is that they do not feel safe.

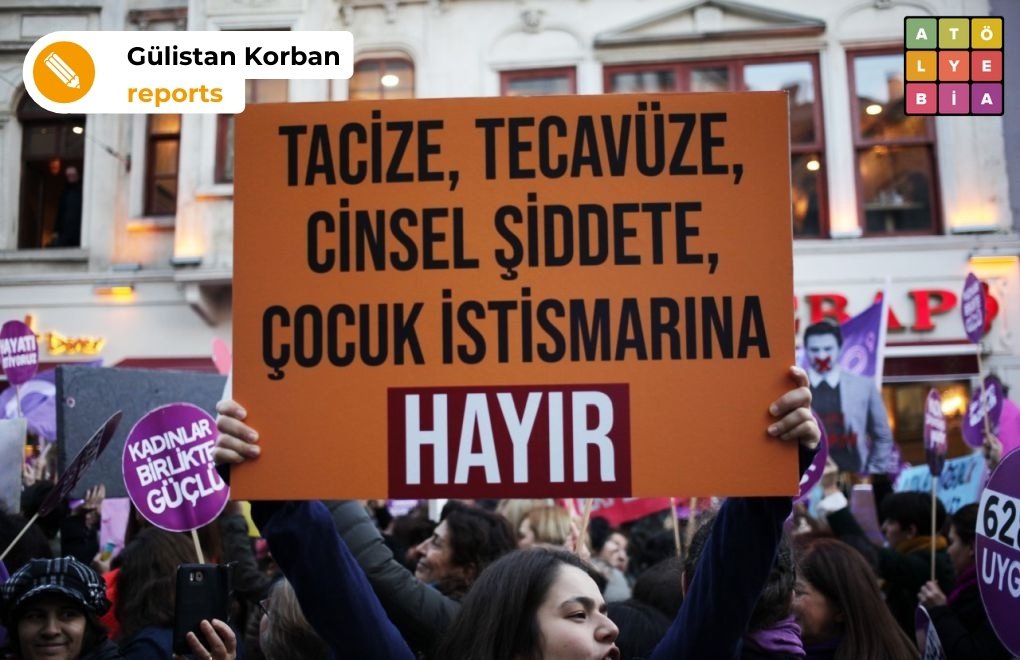

According to the data of the Diyarbakır Bar Association, 60 percent of the refugees who applied to the bar for legal assistance for various reasons from 2018 to 2021 were women. Several applicants asked for assistance related to violence, harassment, divorce and custody.

A recent report of Amnesty International has shown that the number of refugees hit 84 million across the world in 2021. While Turkey ranks 12th in the list of countries that accept the highest numbers of refugees, there are over 6 million refugees under temporary protection in Turkey. Of these people, 3 million 639 thousand and 527 are from Syria.

One of the transit points for refugees is Turkey's Kurdish-majority southeastern province of Diyarbakır, where there are currently 14 thousand 218 Syrian refugees, according to official numbers. NGOs in the province note that the actual number is much higher. (GK/SO/NÖ/SD)

.jpg)